Etchings in the Window, July 22nd, 1837

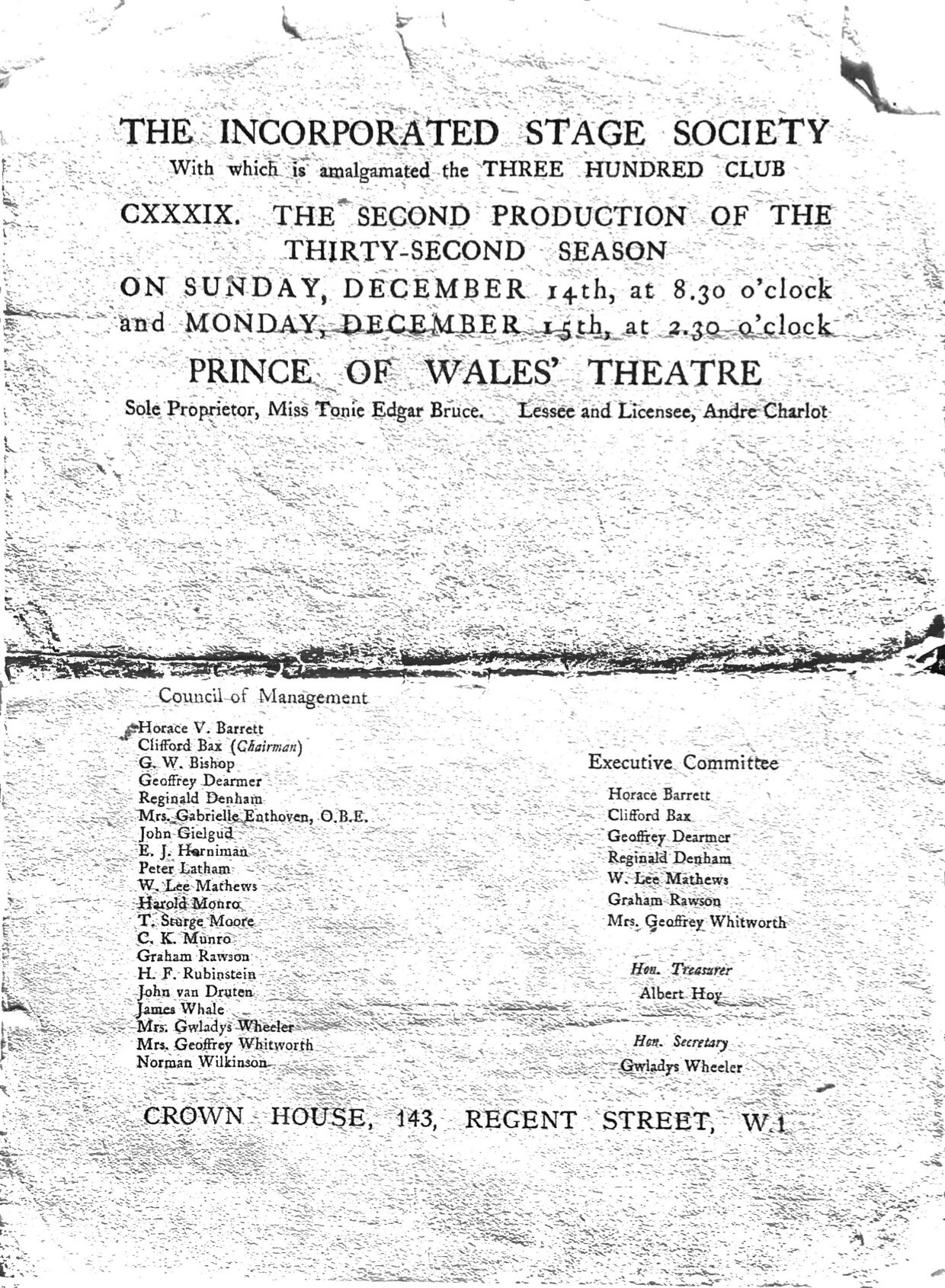

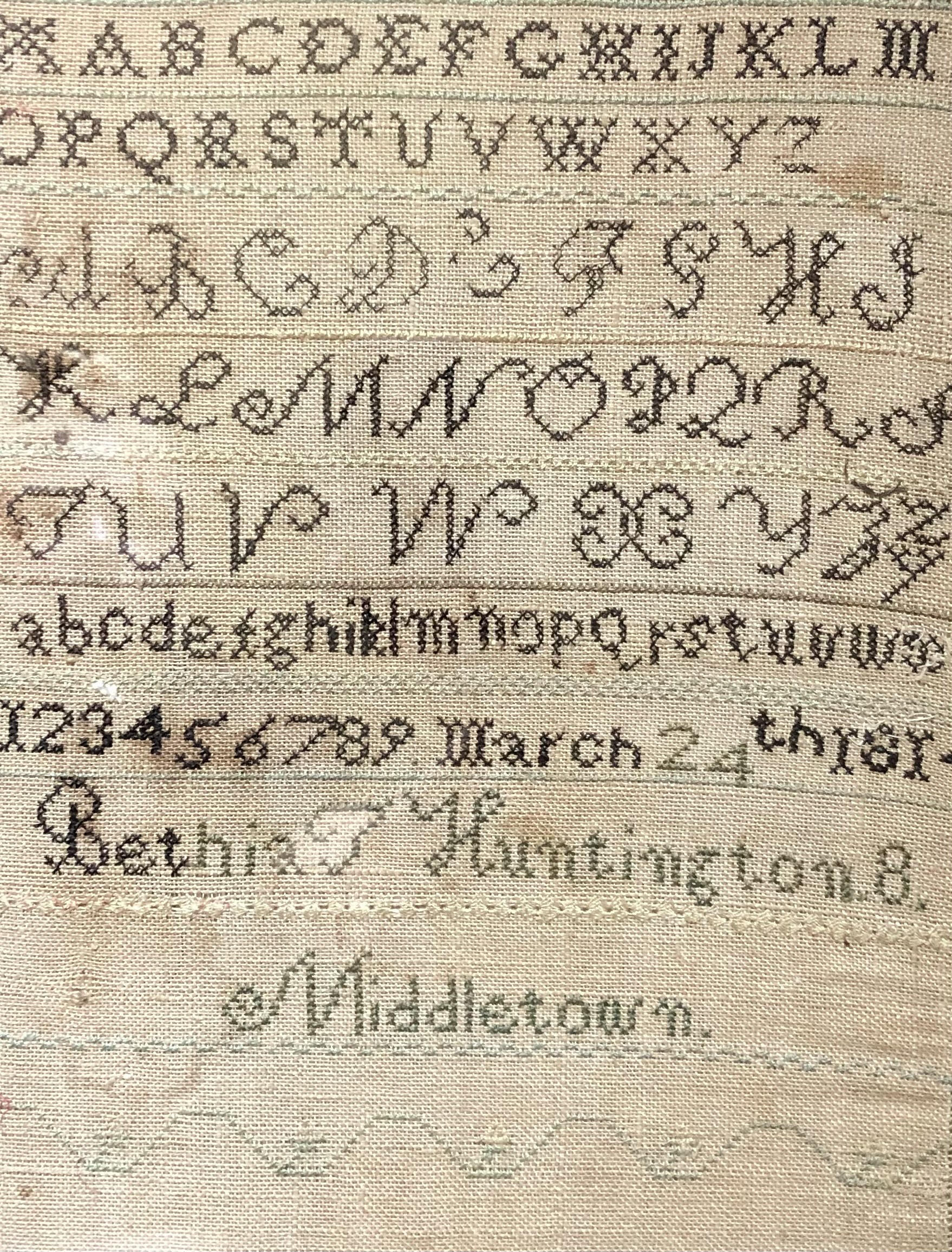

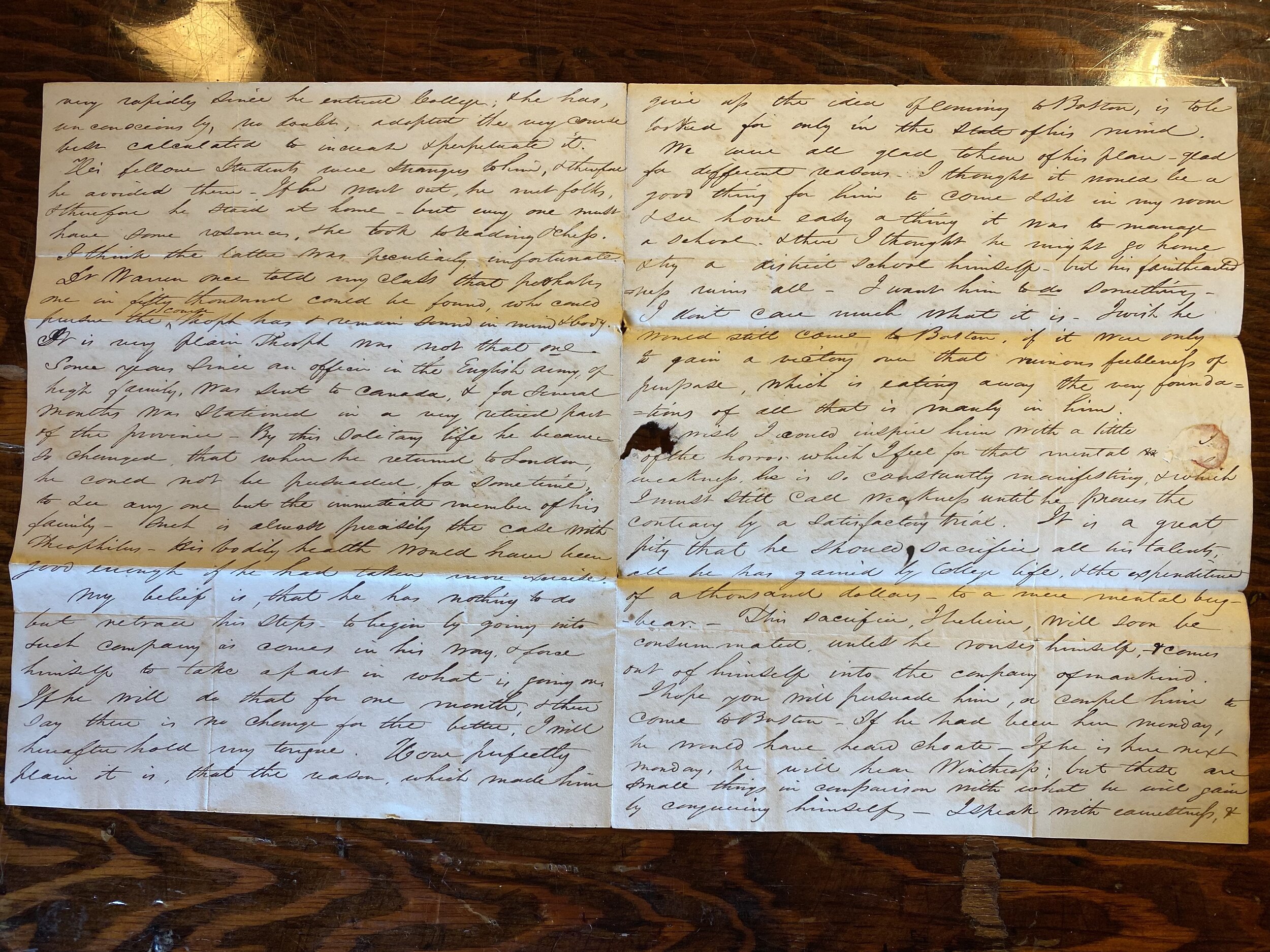

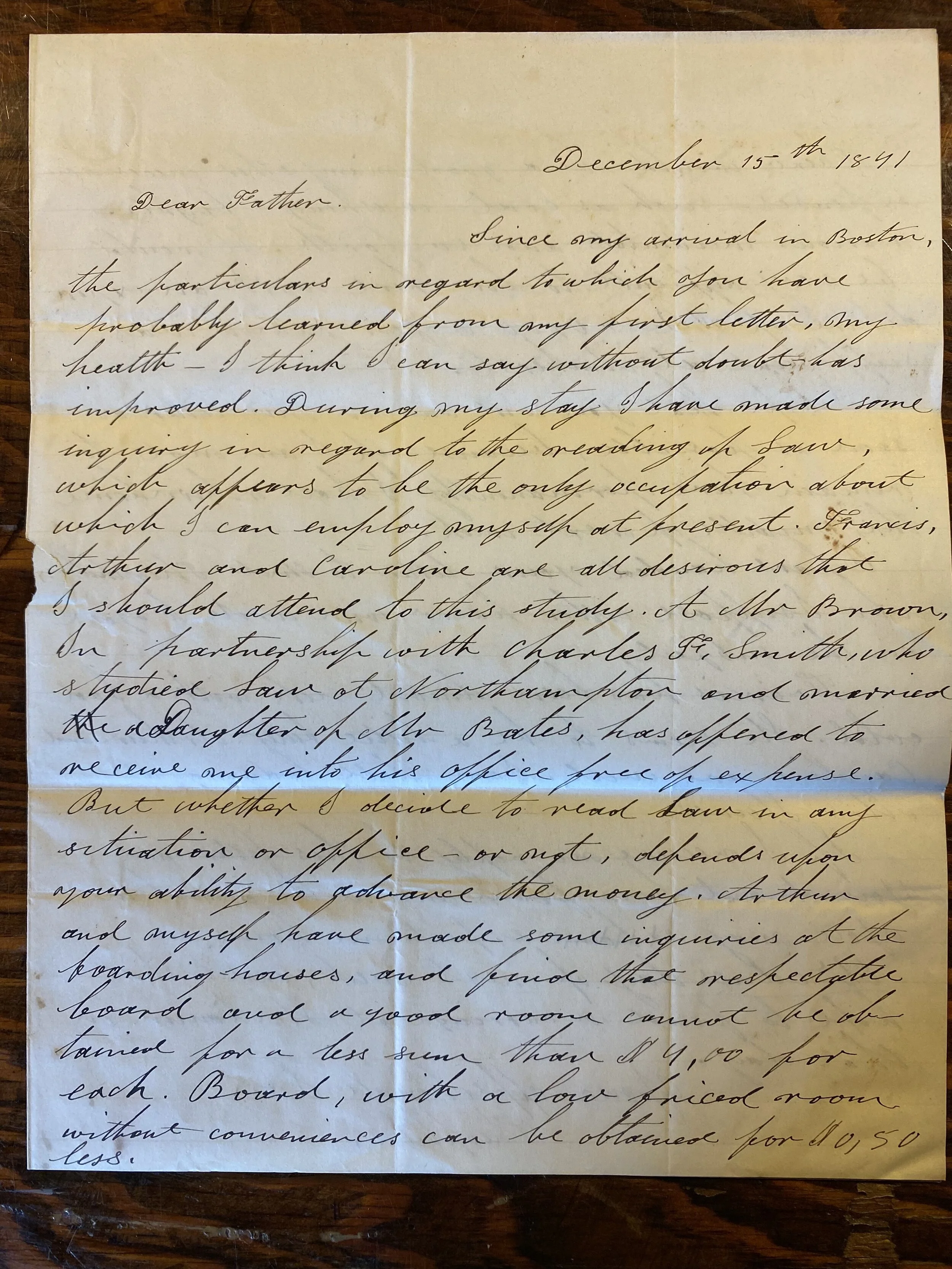

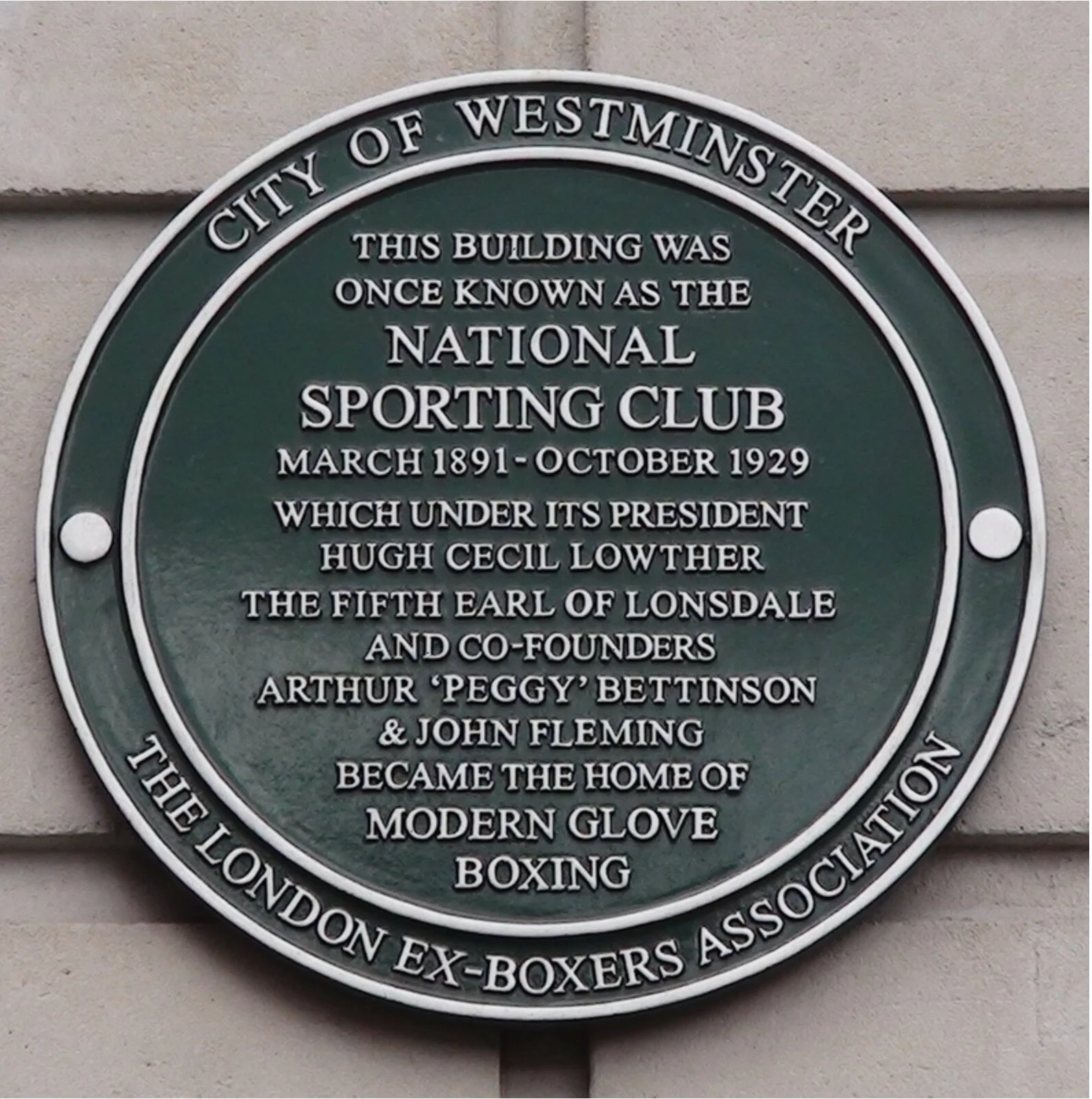

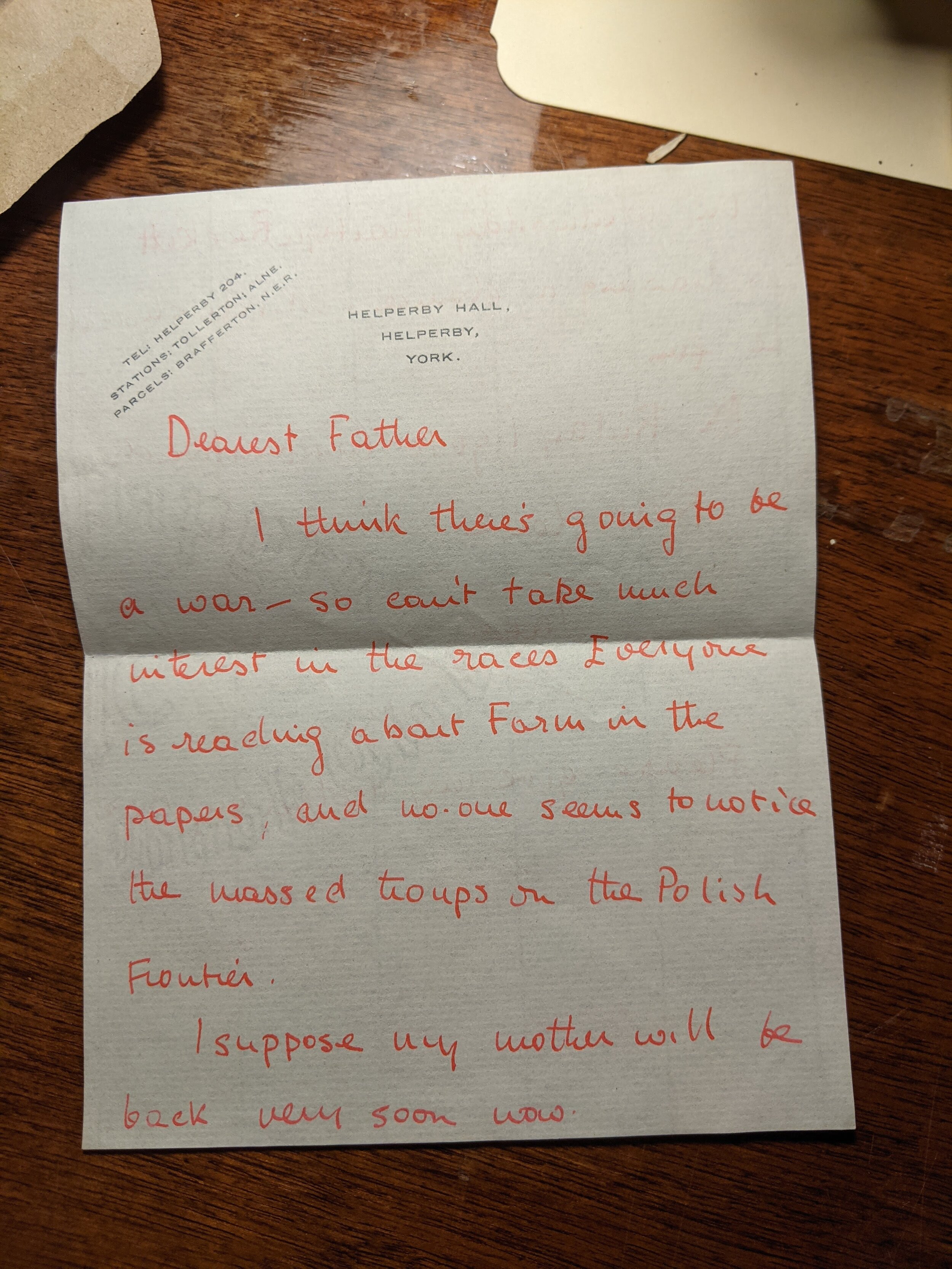

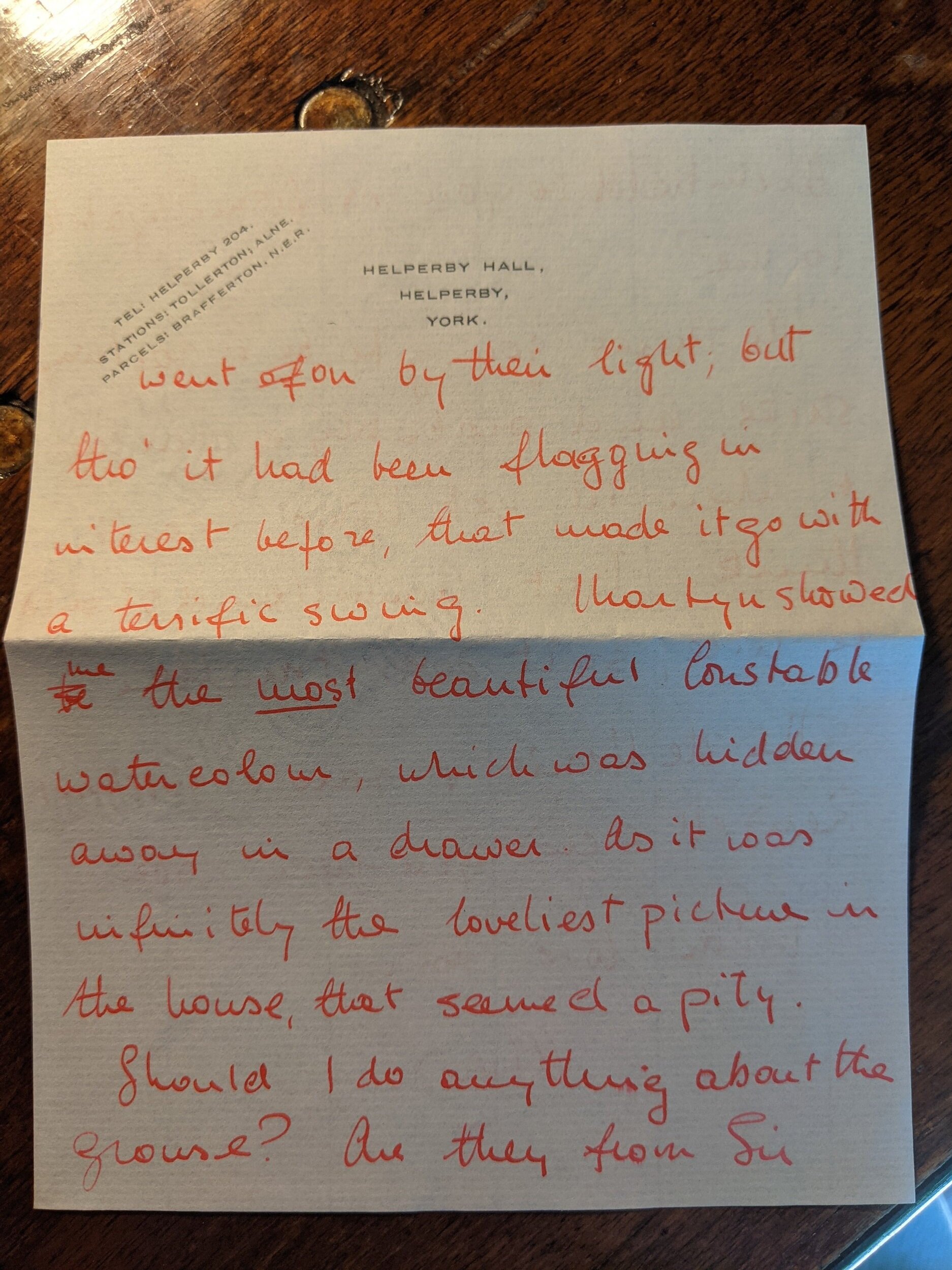

On July 22nd in the Porter-Phelps-Huntington House, 186 years ago, Harriet Blake Mills and Mary Dwight Huntington etched into the window of an upstairs bedroom "H.B.M. 22nd July 1837,” and faintly, "Mary Dwight Huntington, July 22nd."

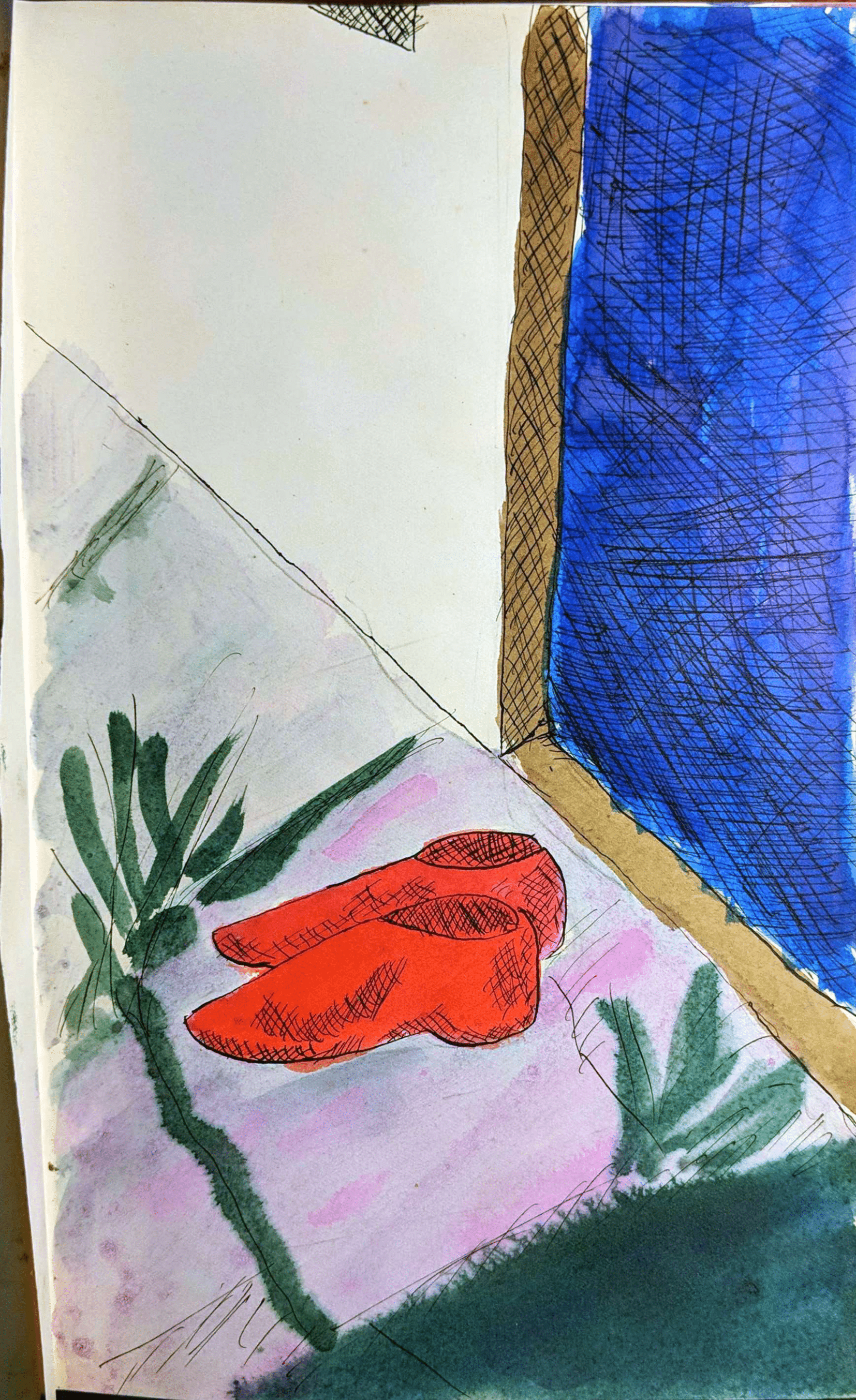

The faint etchings outlined in red for visibility

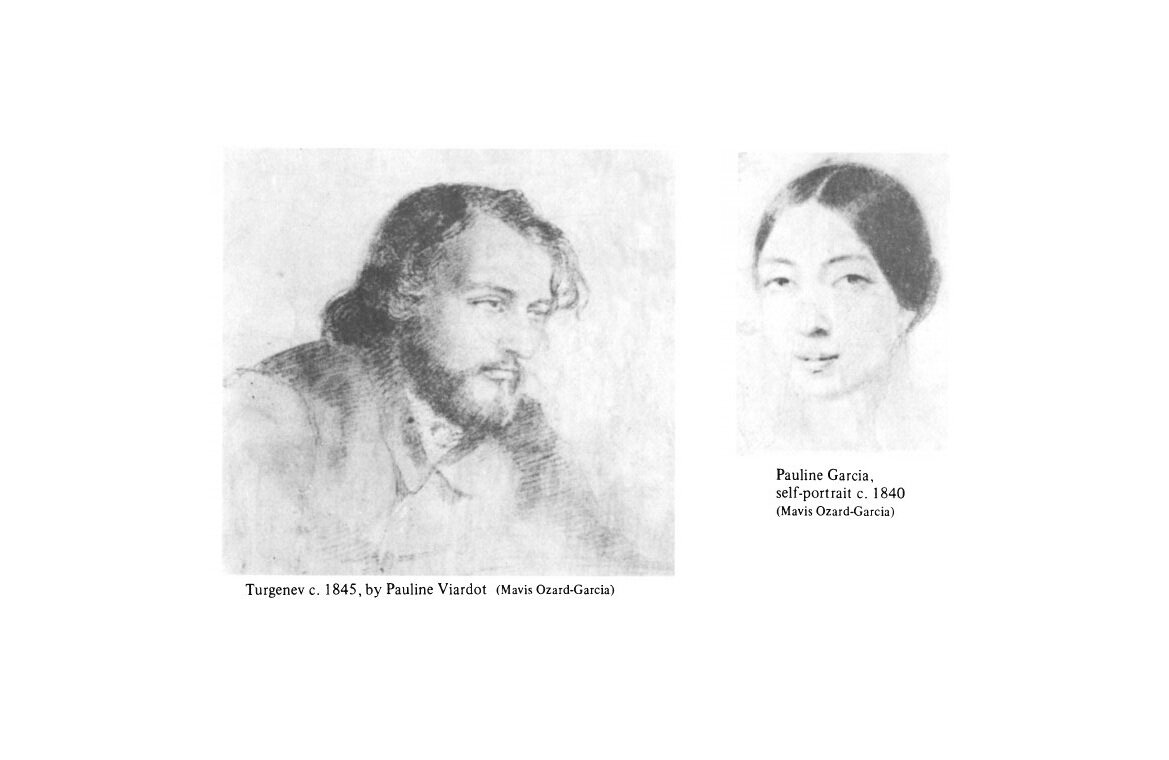

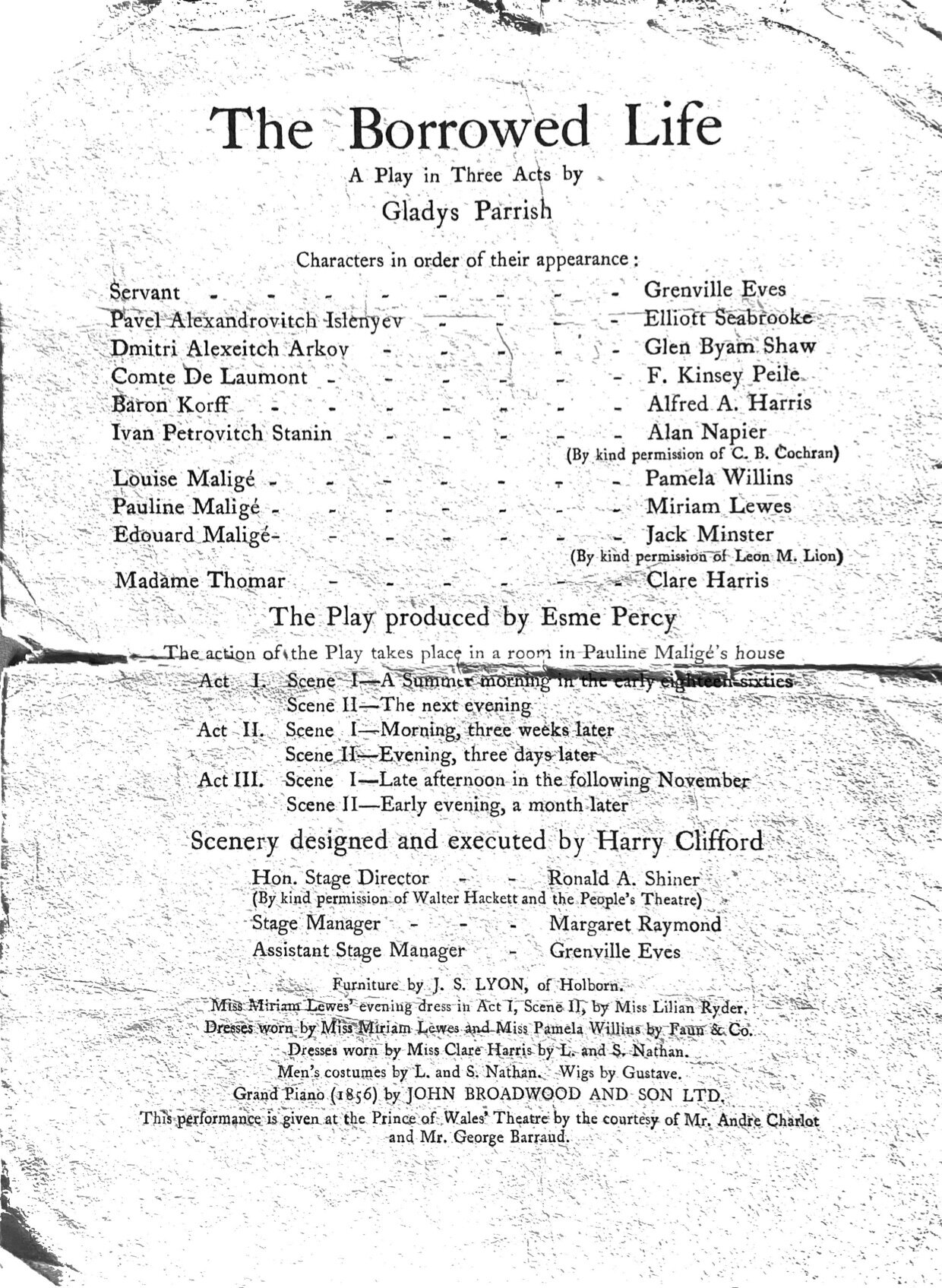

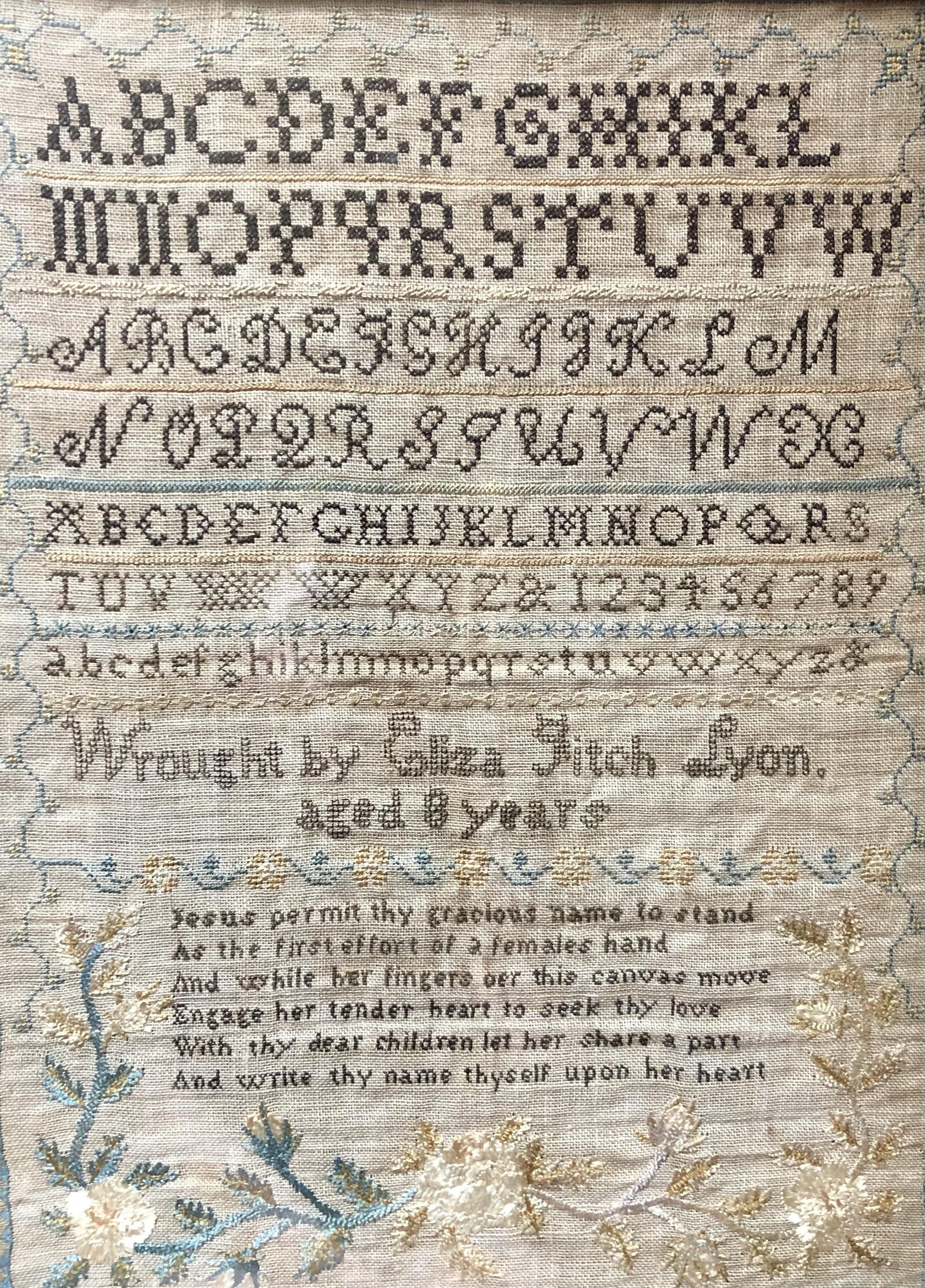

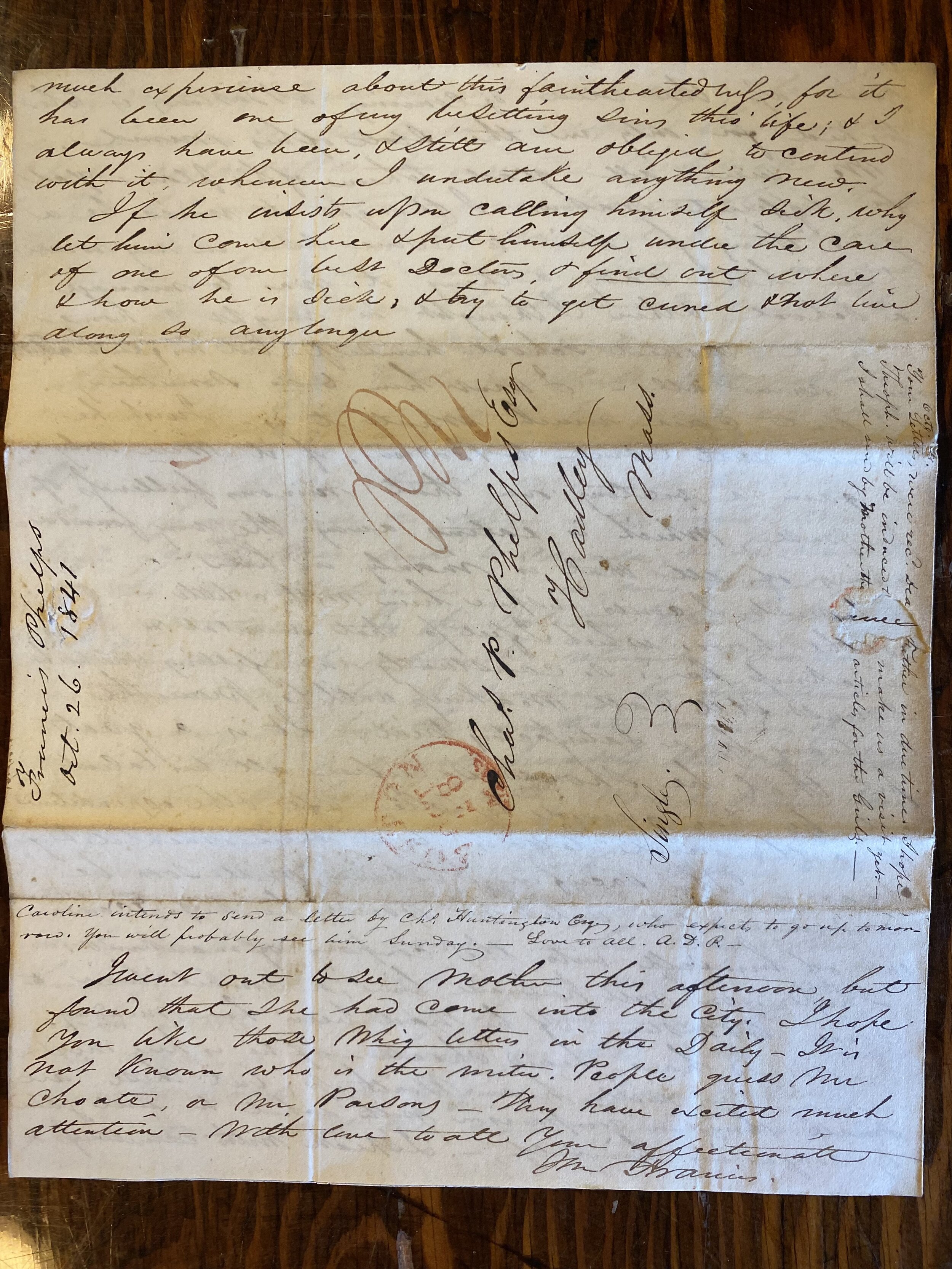

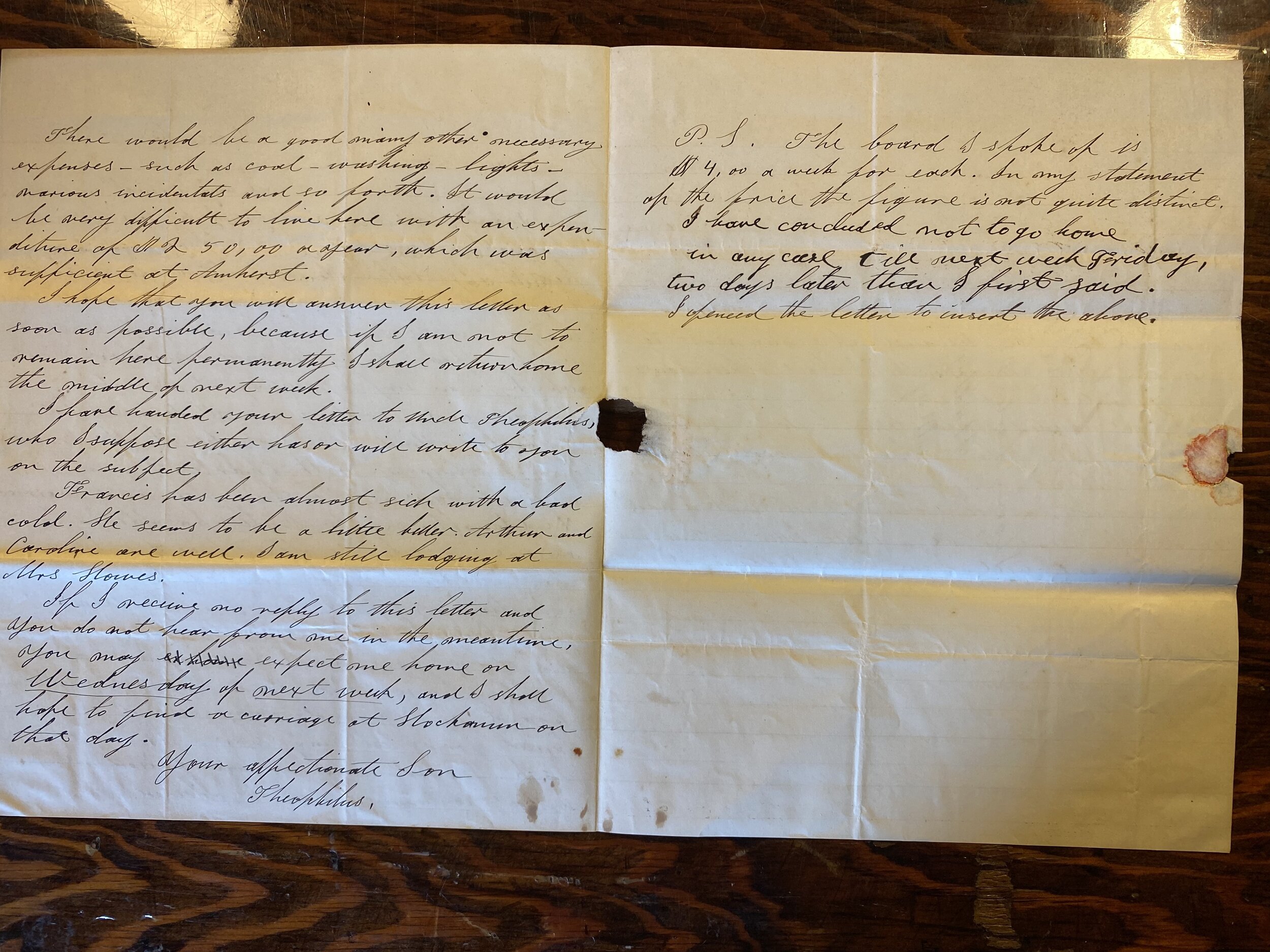

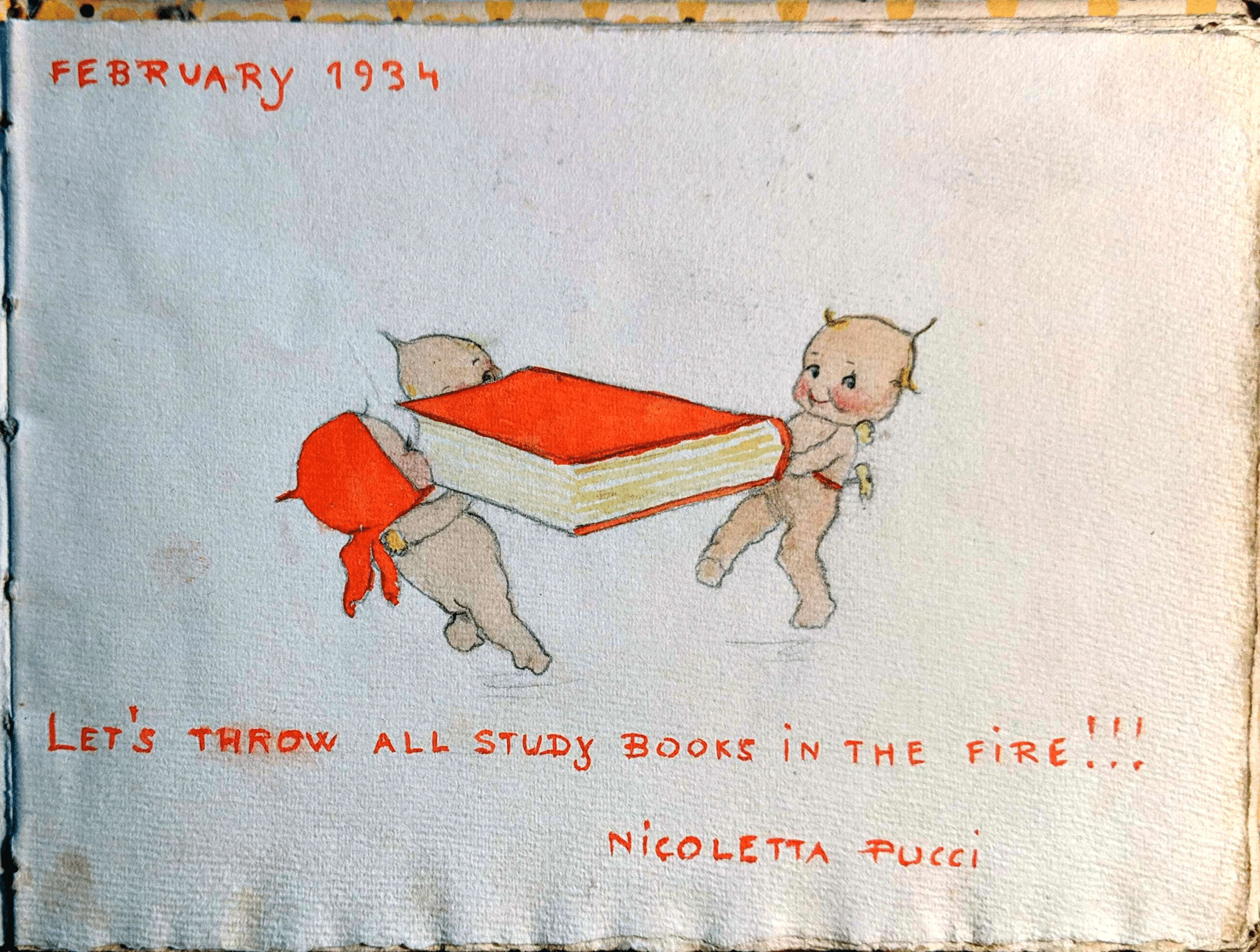

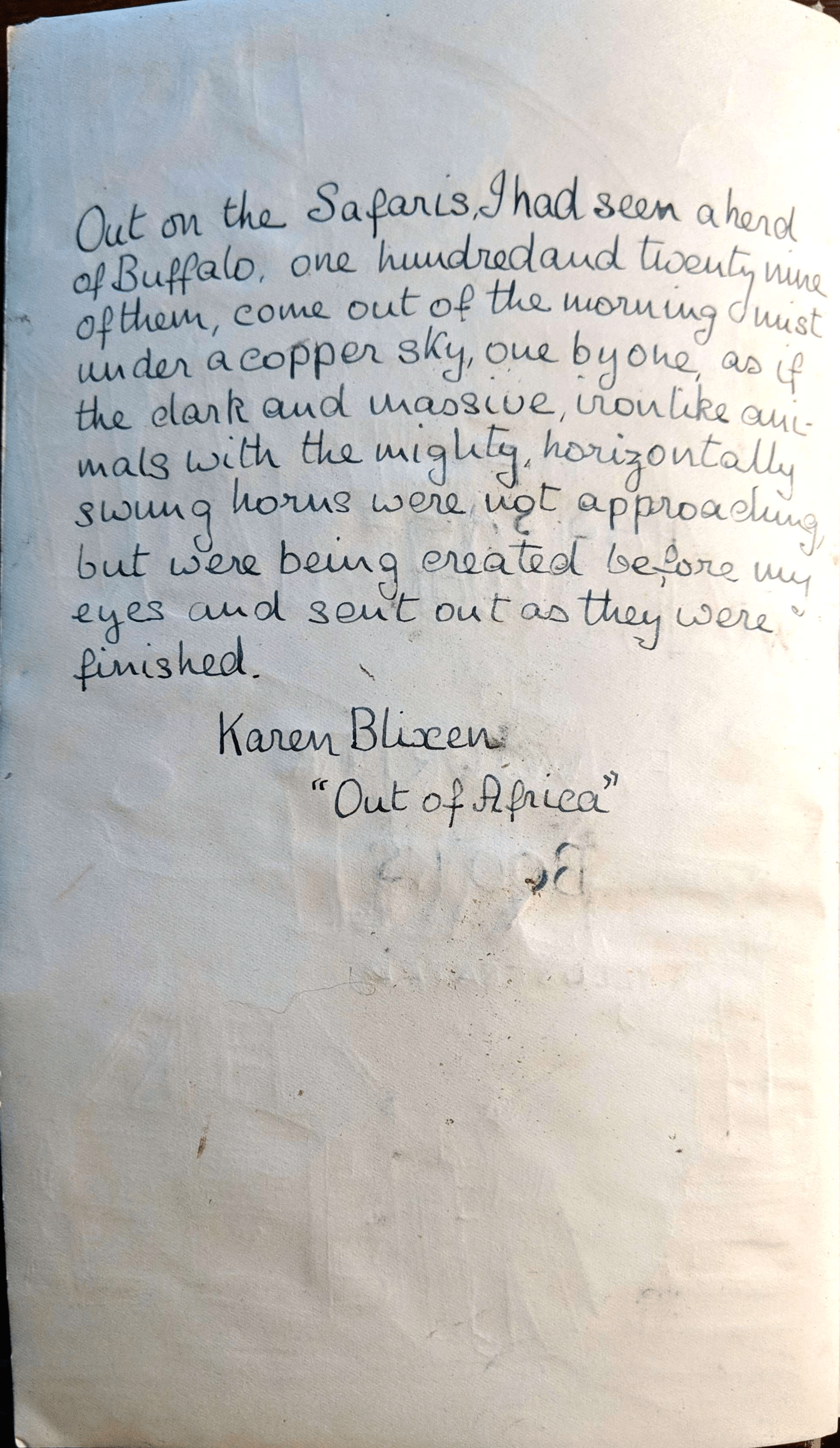

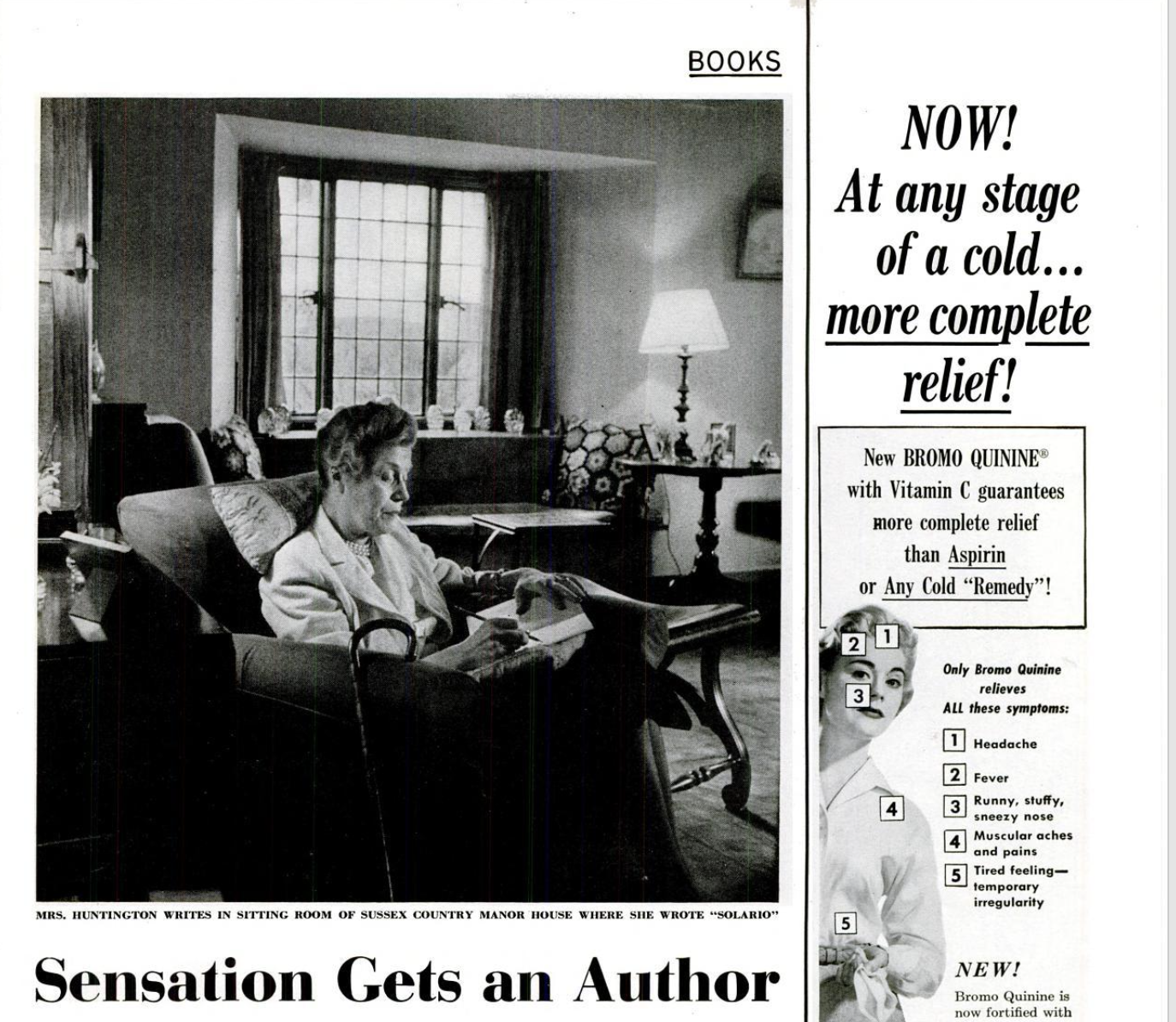

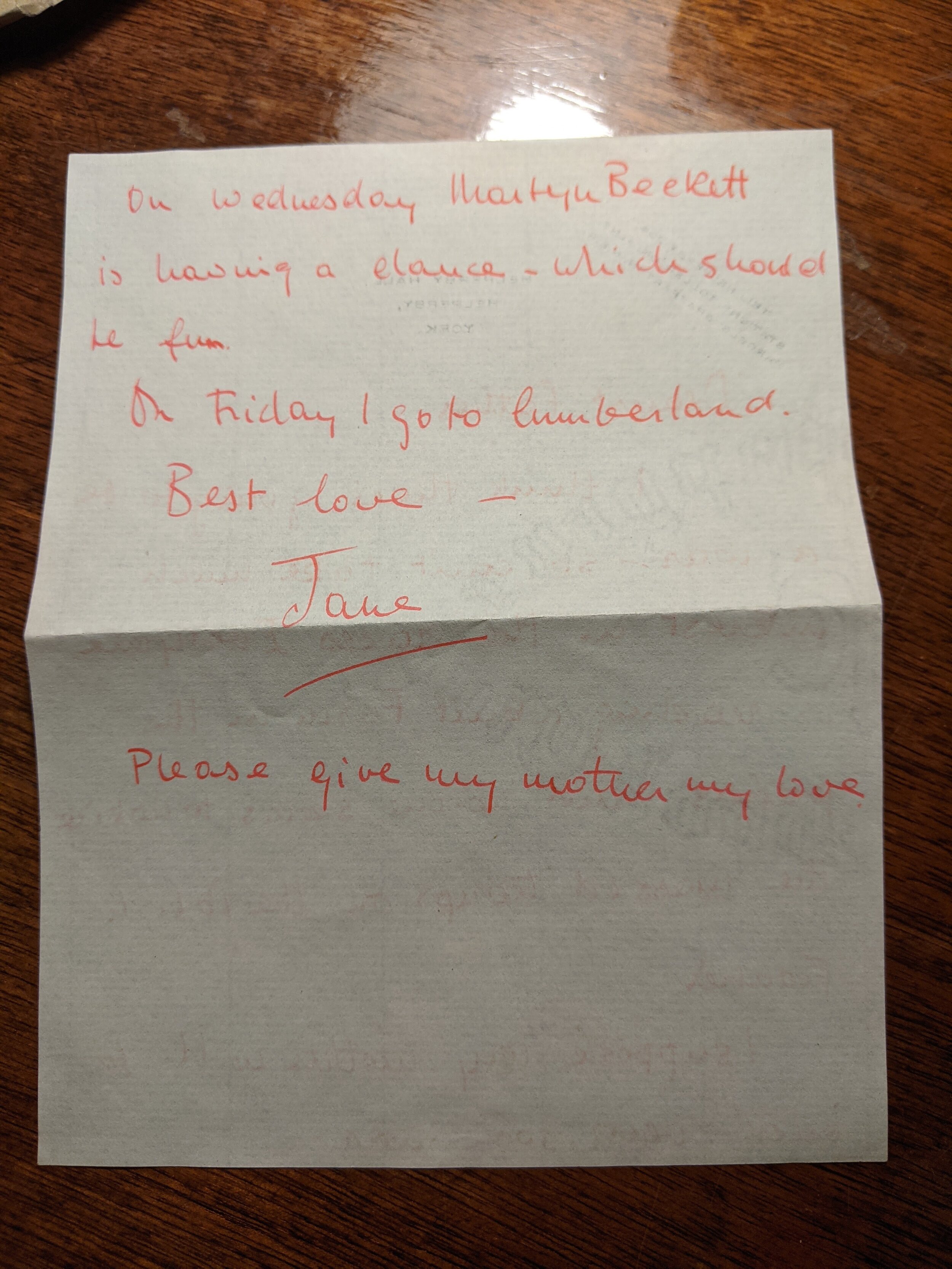

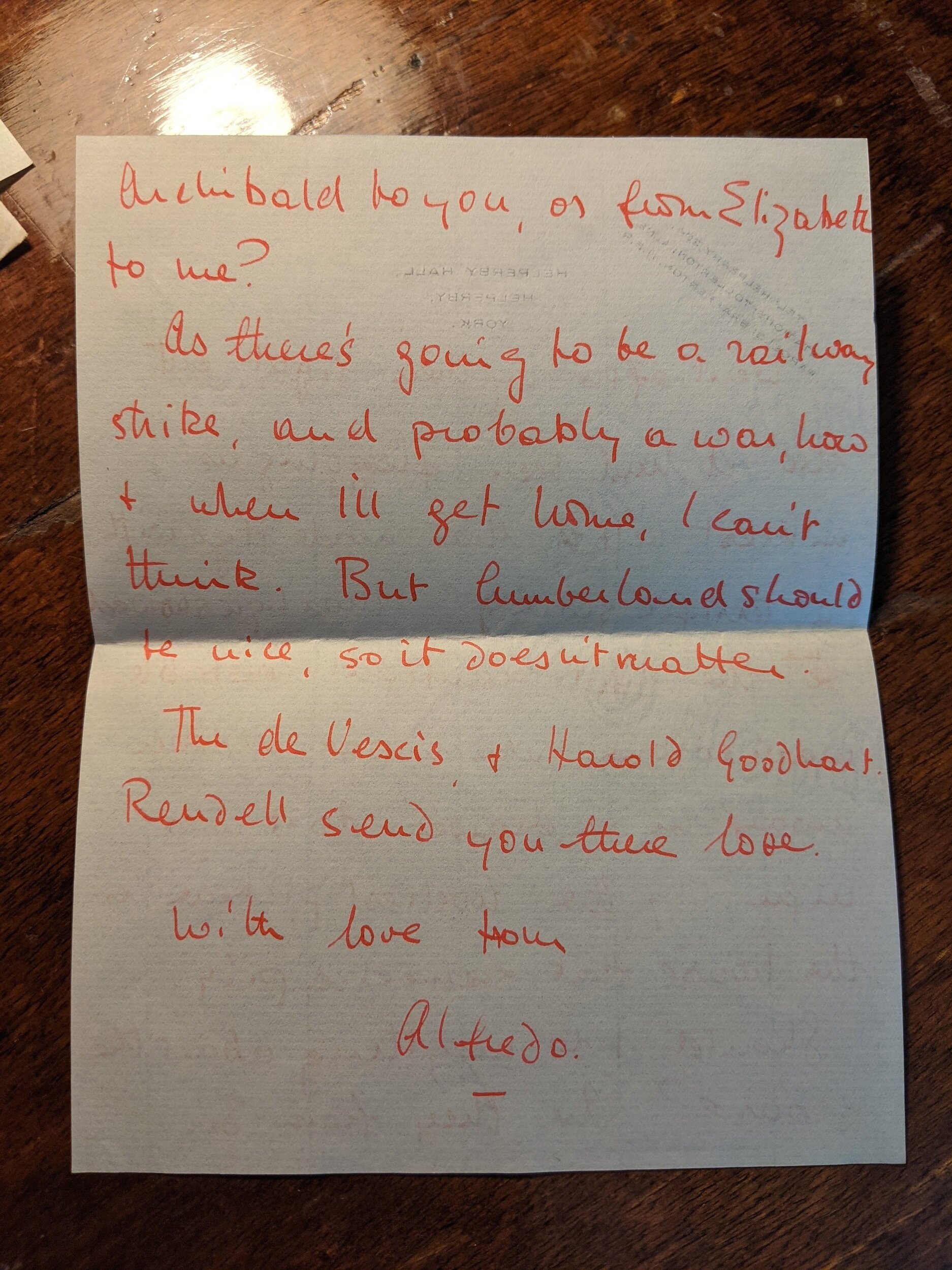

Etching one’s name into a window, likely with a diamond ring, was not uncommon during the 19th-century. Many other instances of names etched into windows can be found in residences, museums, and university buildings across the country. In 1843, Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne would use Sophia’s diamond ring to etch messages into the windowpane at The Old Manse in Concord, MA.

Etchings in the window of The Old Manse in Concord, MA.

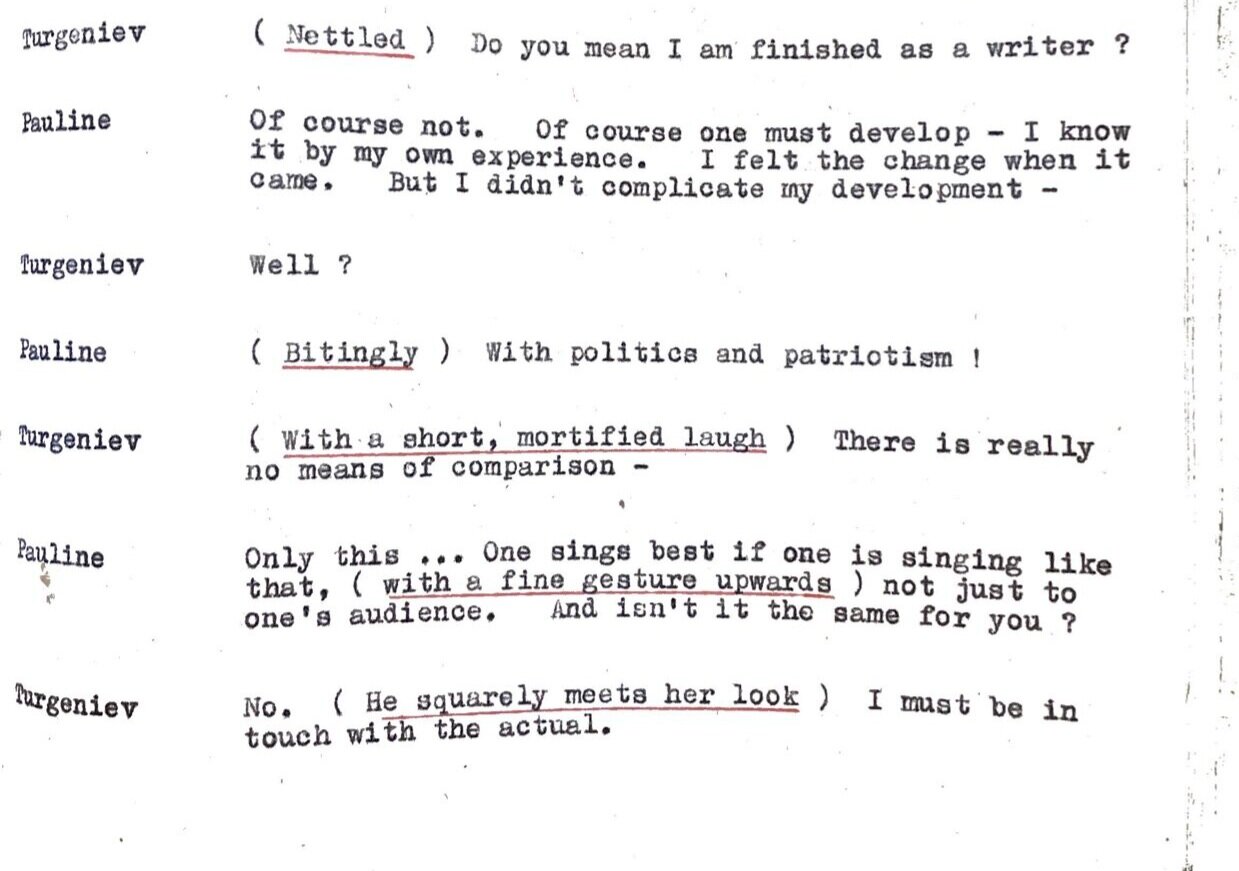

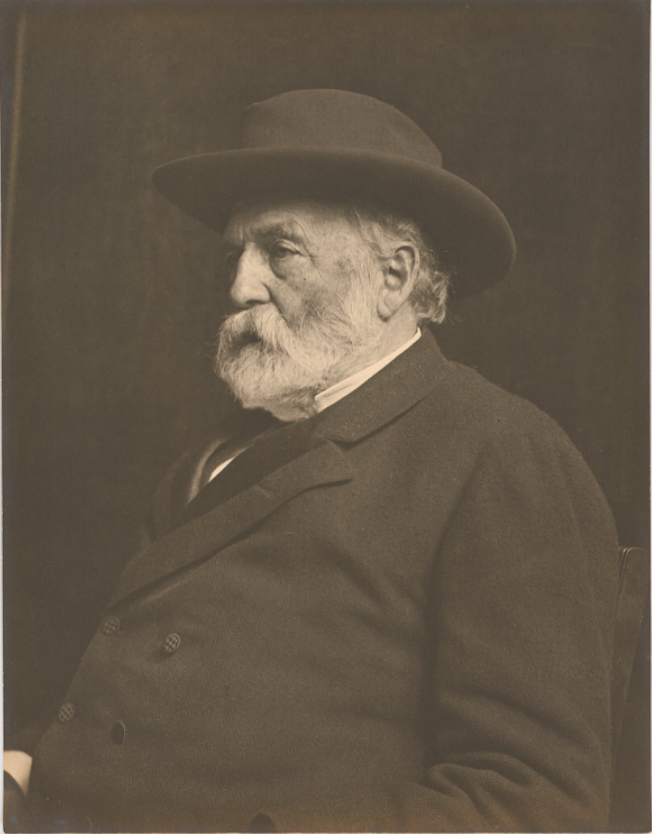

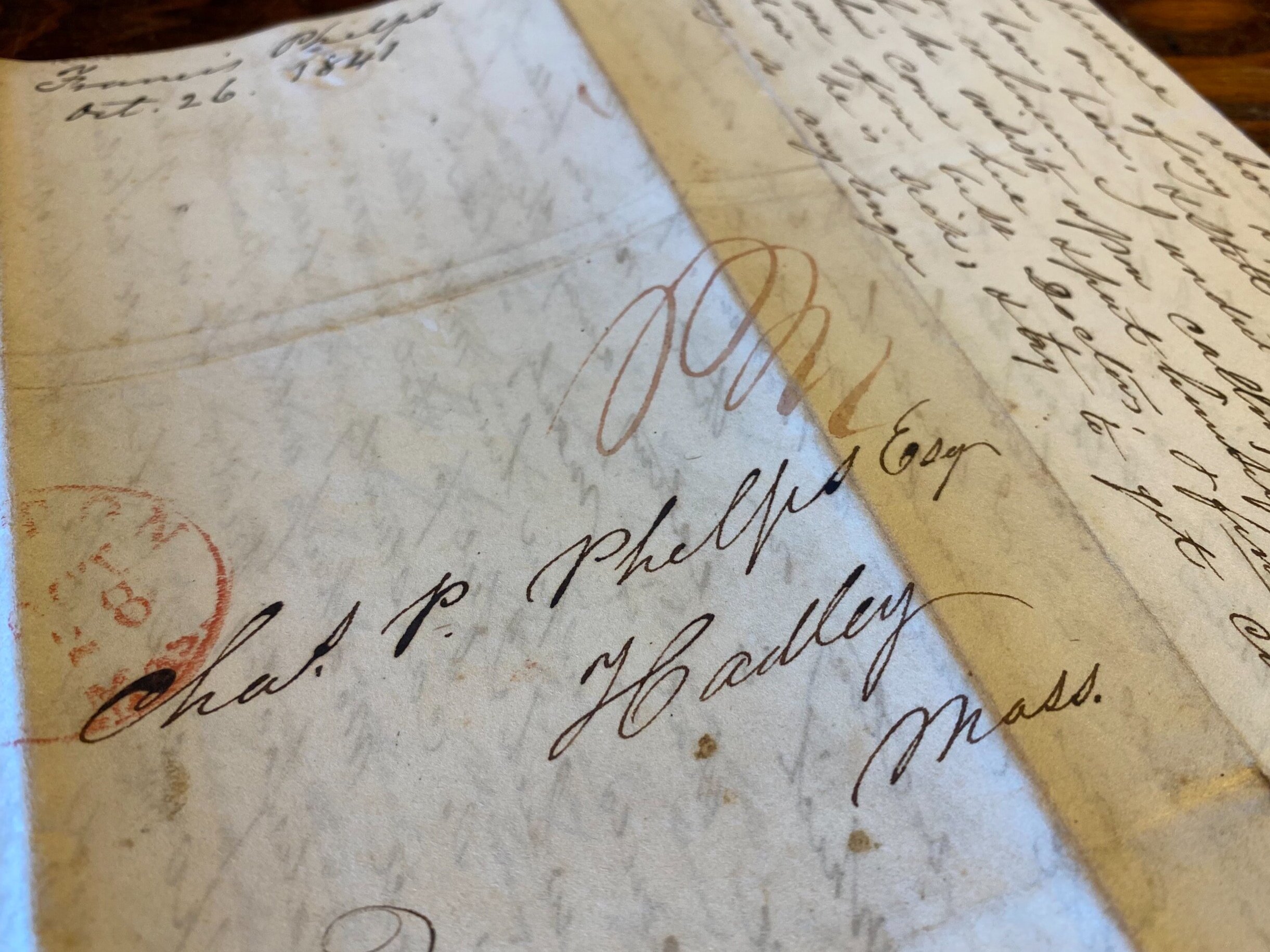

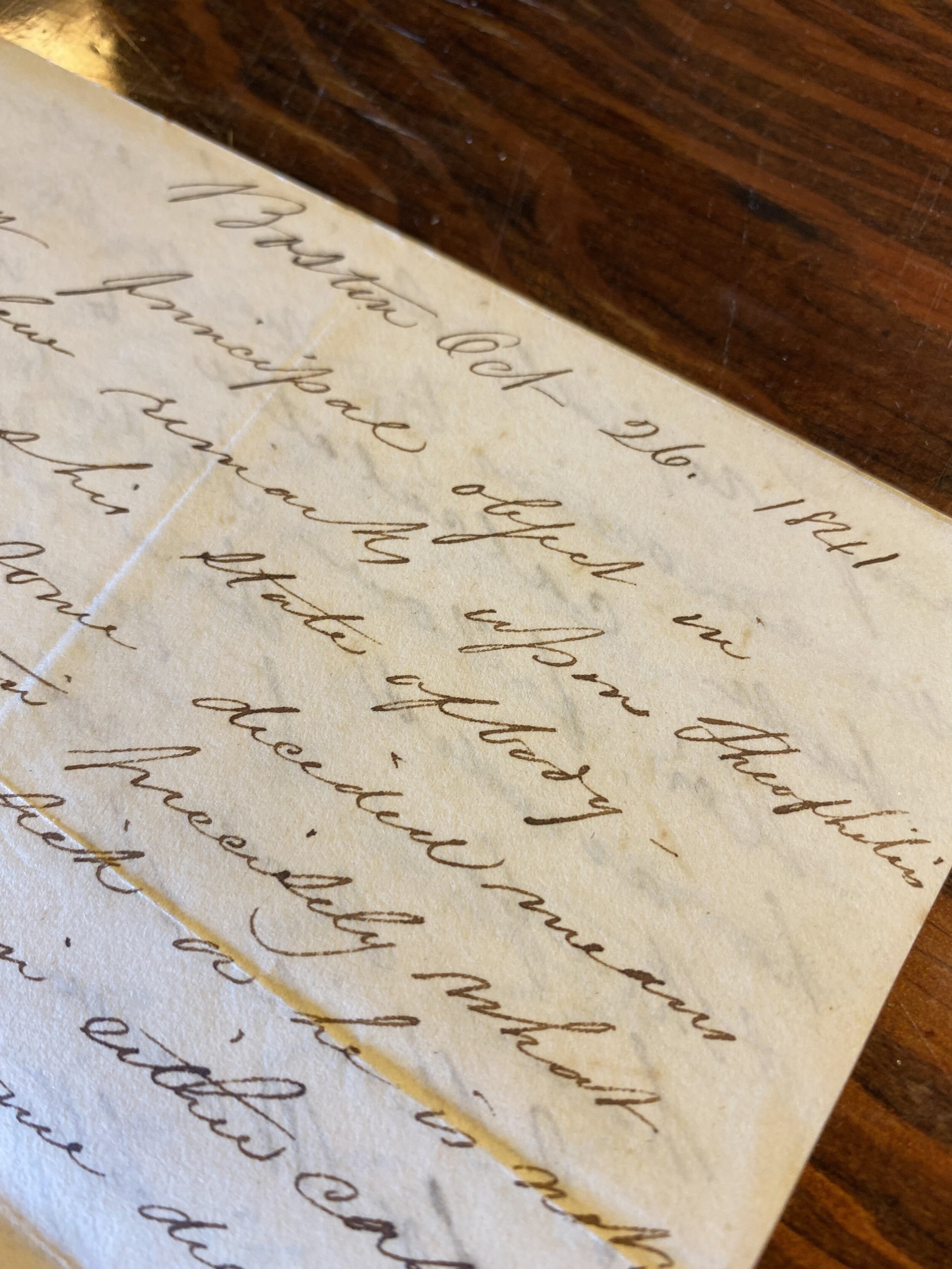

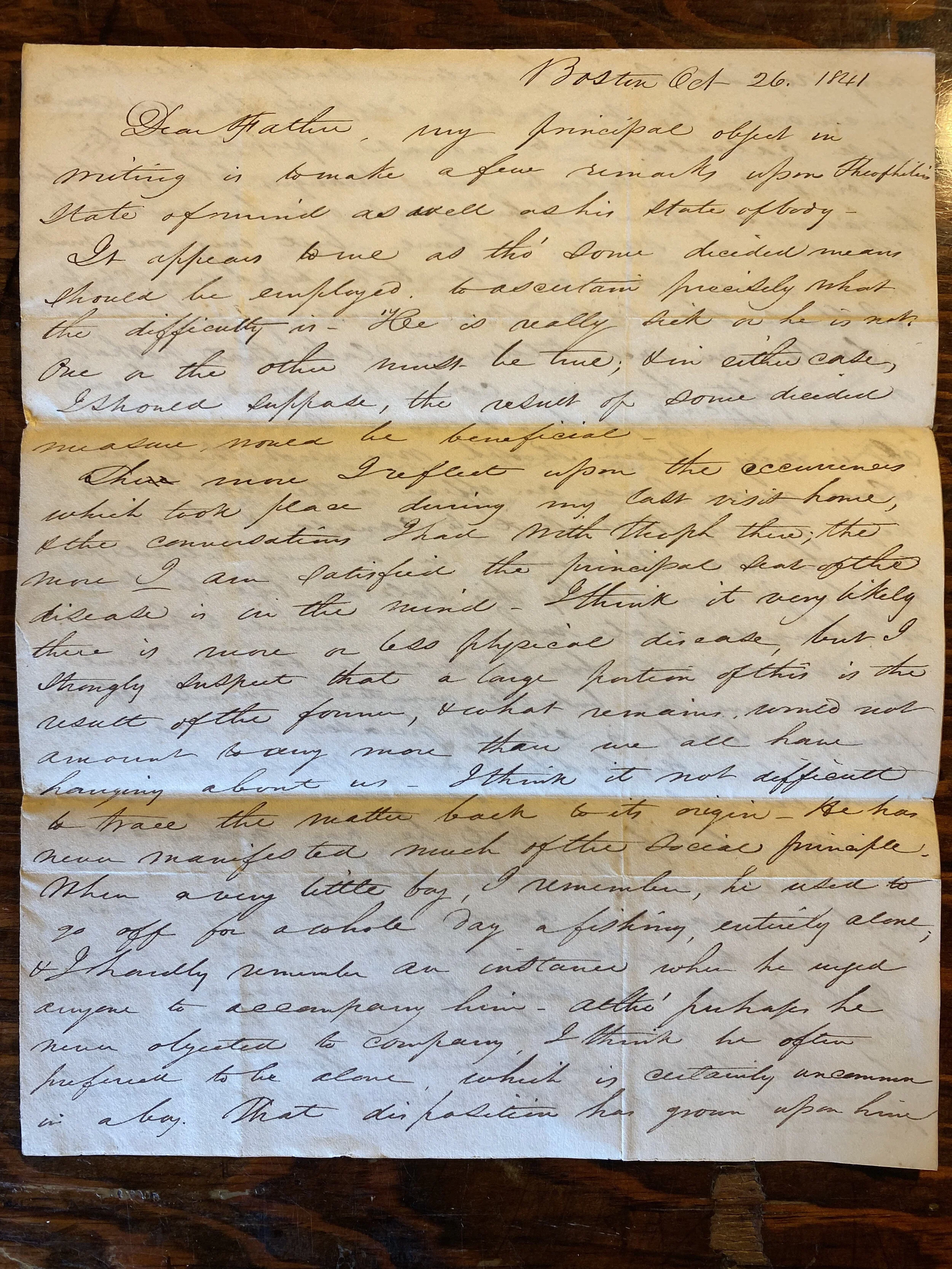

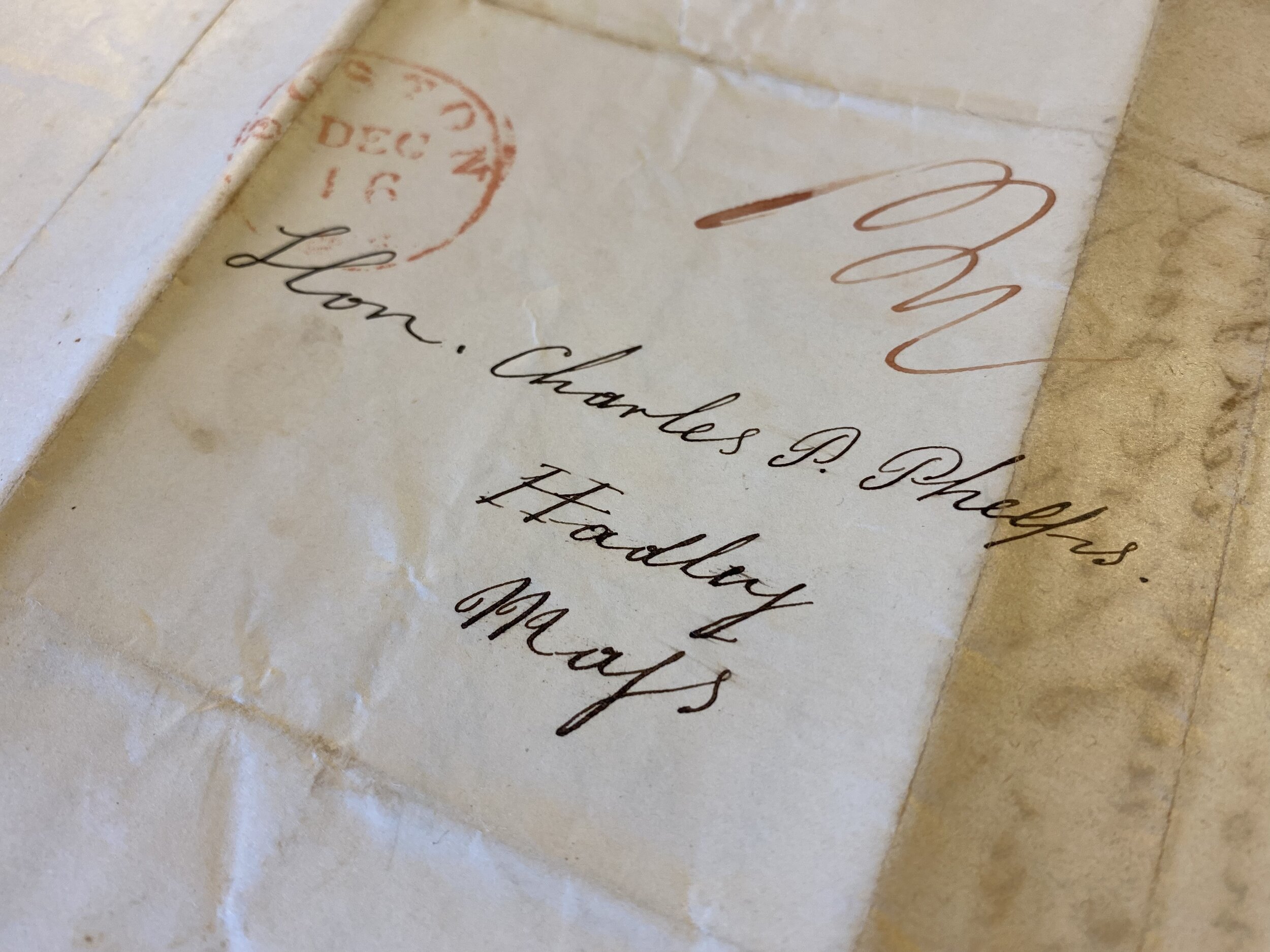

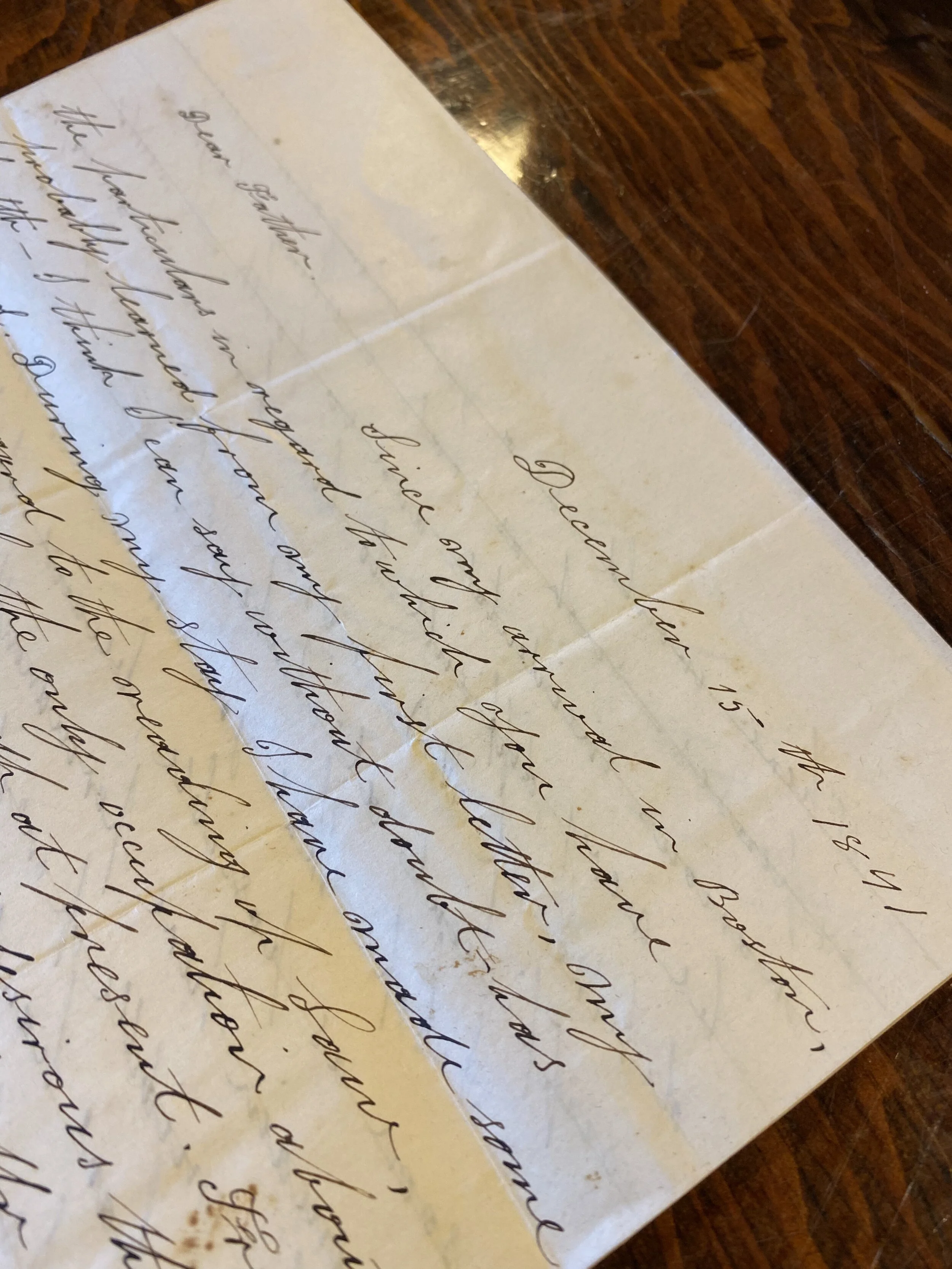

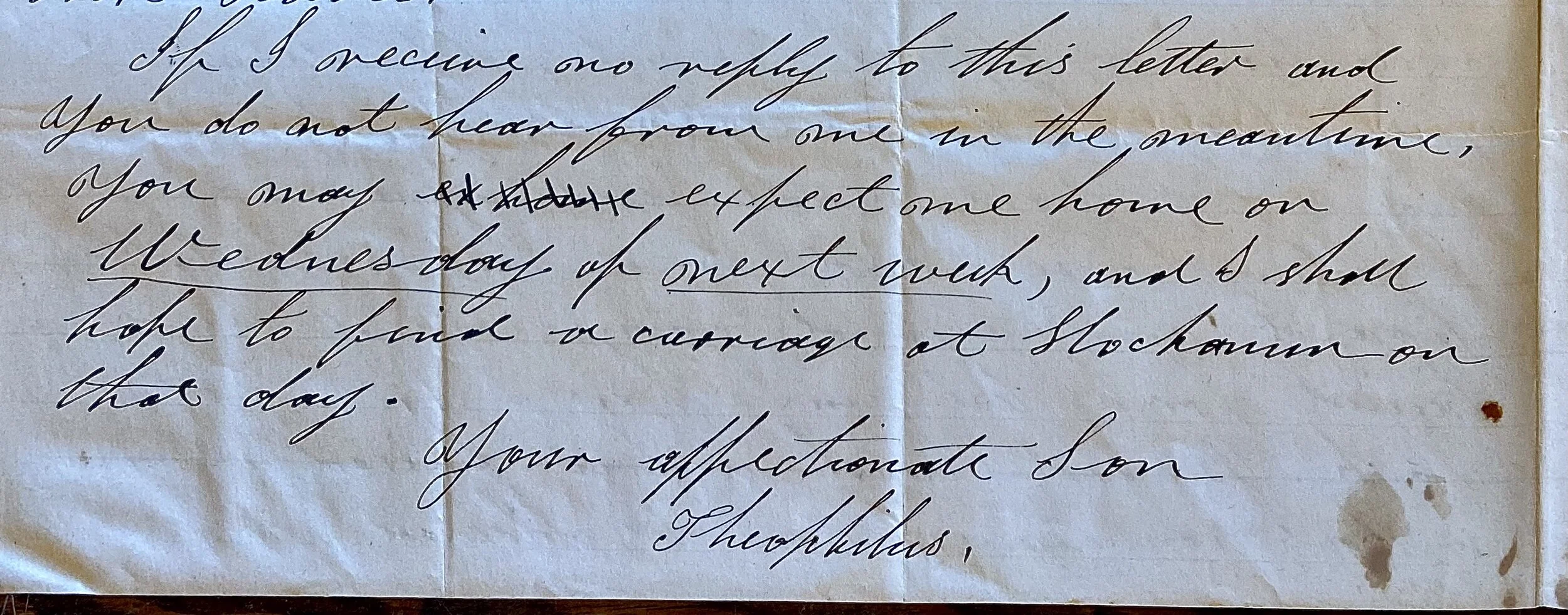

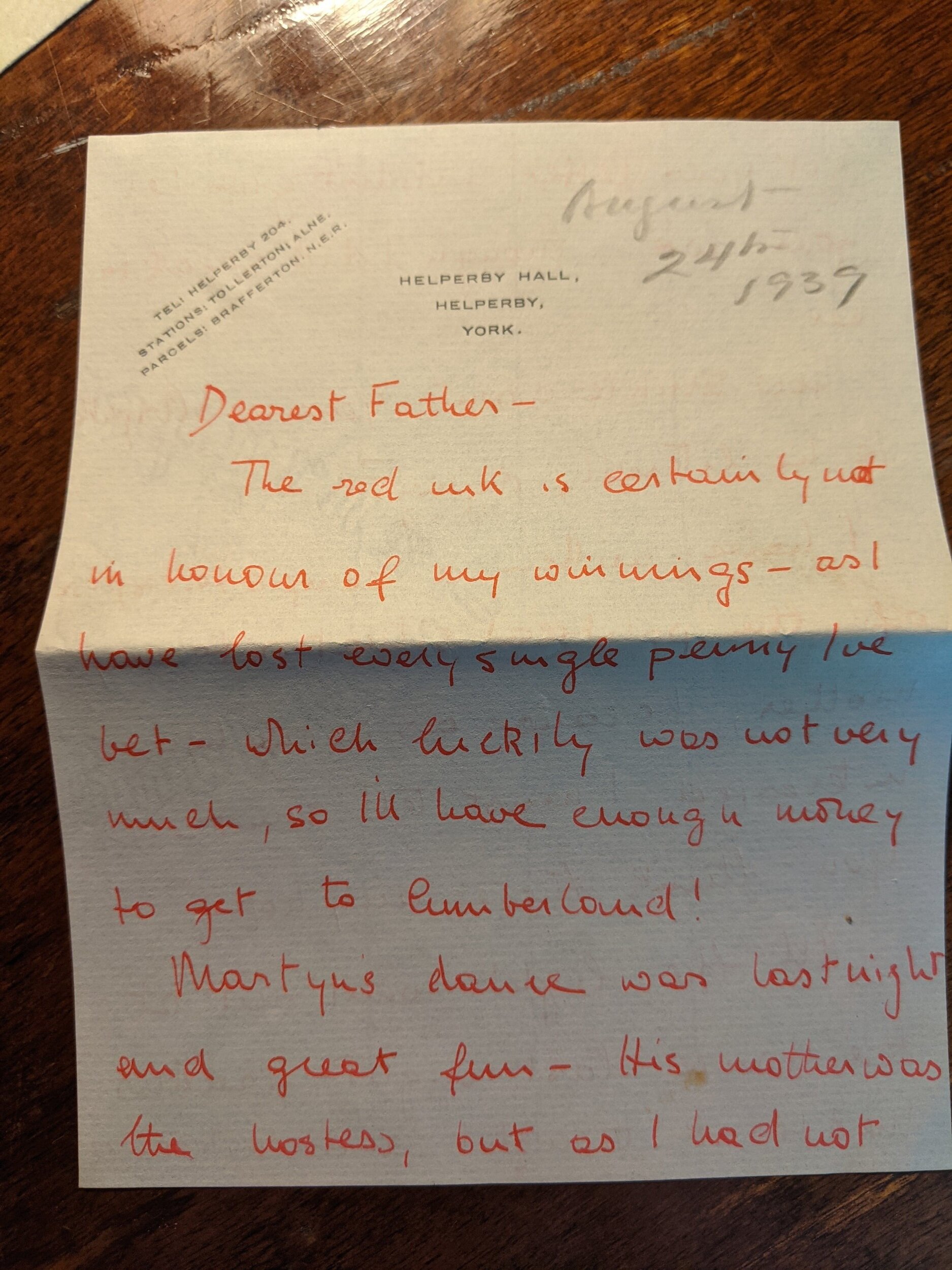

Mary Dwight Huntington (1815-1839) was the daughter of Dan Huntington and Elizabeth Whiting Phelps Huntington. H.B.M. is likely Harriet Blake Mills (1818-1892), the sister-in-law to Charles Phelps Huntington (1802-1868), who was the eldest child of Dan and Elizabeth. Harriet, born in Northampton in 1818, would have been just 3 years younger than Mary. Two days after the etching, on July 24th, Elizabeth Huntington wrote to Edward Huntington, “Charles and his family dined with us one day last week. They brought over Harriette and left her with us till Saturday.” It was a Saturday on July 22nd in 1837 when the two women etched their names into the window at the Porter-Phelps-Huntington house.

“Charles and his family dined with us one day last week. They brought over Harriette and left her with us till Saturday.” July 24th, 1837

Mary Dwight Huntington, 22 years old in 1837, would only live to 24. In 1839, she fell ill with fever. She was not alone, as many other family members became ill with presumably the same sickness. Mary’s brother Theodore, Mary’s cousin Sarah Phelps and her sister Marianne, and Caroline Judkins of Hadley all suffered from “fevers” during the month of October. Theodore, Sarah, and Marianne survived their sickness. Caroline died October 8th, and Mary D. Huntington died October 14th, 1839.

“Sarah Phelps and Marianne both very sick yet, the friends were considerably encouraged last week about them, but then seems to have come on a secondary fever with Marianne, which is rather alarming.” October 24, 1839

“Caroline Judkins, who was taken sick at the same time with Theodore, has finished her labours and sufferings, as we hope, and as your aunt said, had probably found Whiting and Catherine, in the great company of the redeemed.” October 9th, 1839. Caroline Judkins died October 8th.

“My dear Edward, Our dear Mary has been sinking rapidly since Thursday night; & will not probably live out this day.” October 12th, 1839

“Dear Edward, We still live, and are all gaining strength, thro’ the mercy of our God upon us. There is a breach in our number, and we miss at every step our dear Mary, who was so much the life of our family circle.” October 24th, 1839, ten days after the death of Mary.

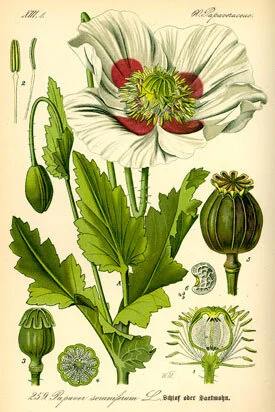

It is likely that Mary and her family experienced an outbreak of typhus or typhoid. Two years prior, in 1837, a typhus epidemic swept through Philadelphia, and throughout the 19th-century both typhus and typhoid were common; typhus was also a significant disease during the Civil War. Typhus and typhoid have similar symptoms, often described as “a sudden onset of fever and other flu-like symptoms about one to two weeks after being infected.”¹ This would conform with the numerous mentions of “fever” throughout the family letters during this period referring to the sick.

Until recently, the identities of those who had etched their names into the window at the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum have been shrouded in mystery. With this new research, we know that Mary D. Huntington was the one to leave her mark just a few years before her untimely death. We’re now able to look at the moment in 1837 as perhaps a happy shared moment of bonding between Mary and Harriet that created a memorial to Mary’s short life.

Sources:

¹ Mullen, Gary R., Lance A. Durden, and Jonas King. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. London: Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier, 2019.

“Nooks and Crannies: Uncovering the Secrets of the Old Manse.” LivingConcord. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.livingconcord.com/event/nooks-and-crannies-uncovering-the-secrets-of-the-old-manse/.

“Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers.” Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, Global Valley. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.ats.amherst.edu/globalvalley/exhibits/show/pph-papers.

“What an 1836 Typhus Outbreak Taught the Medical World about Epidemics.” Smithsonian.com, April 21, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-1836-typhus-outbreak-taught-medical-world-about-epidemics-180974707/.