The Contentious History of Midwifery in Massachusetts

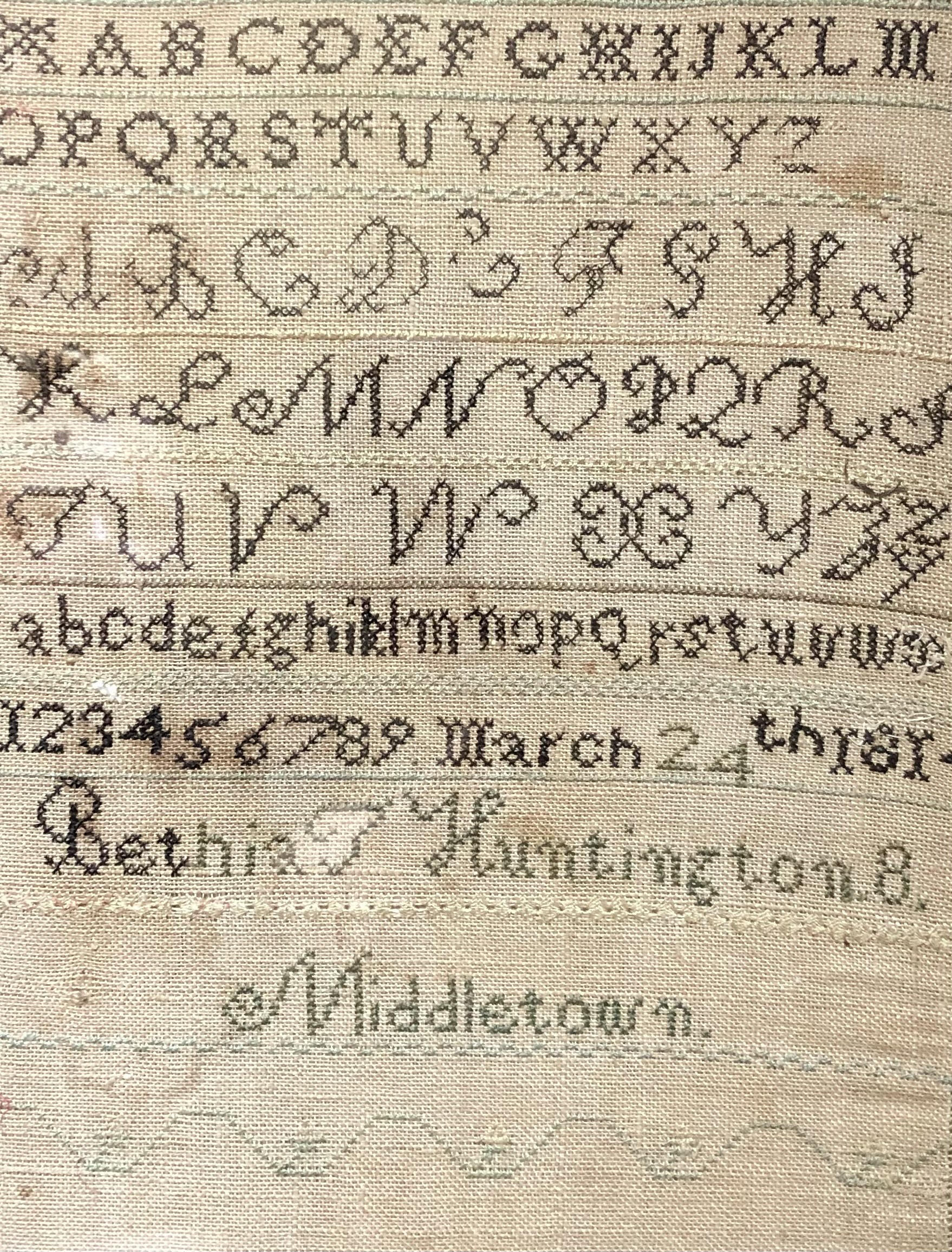

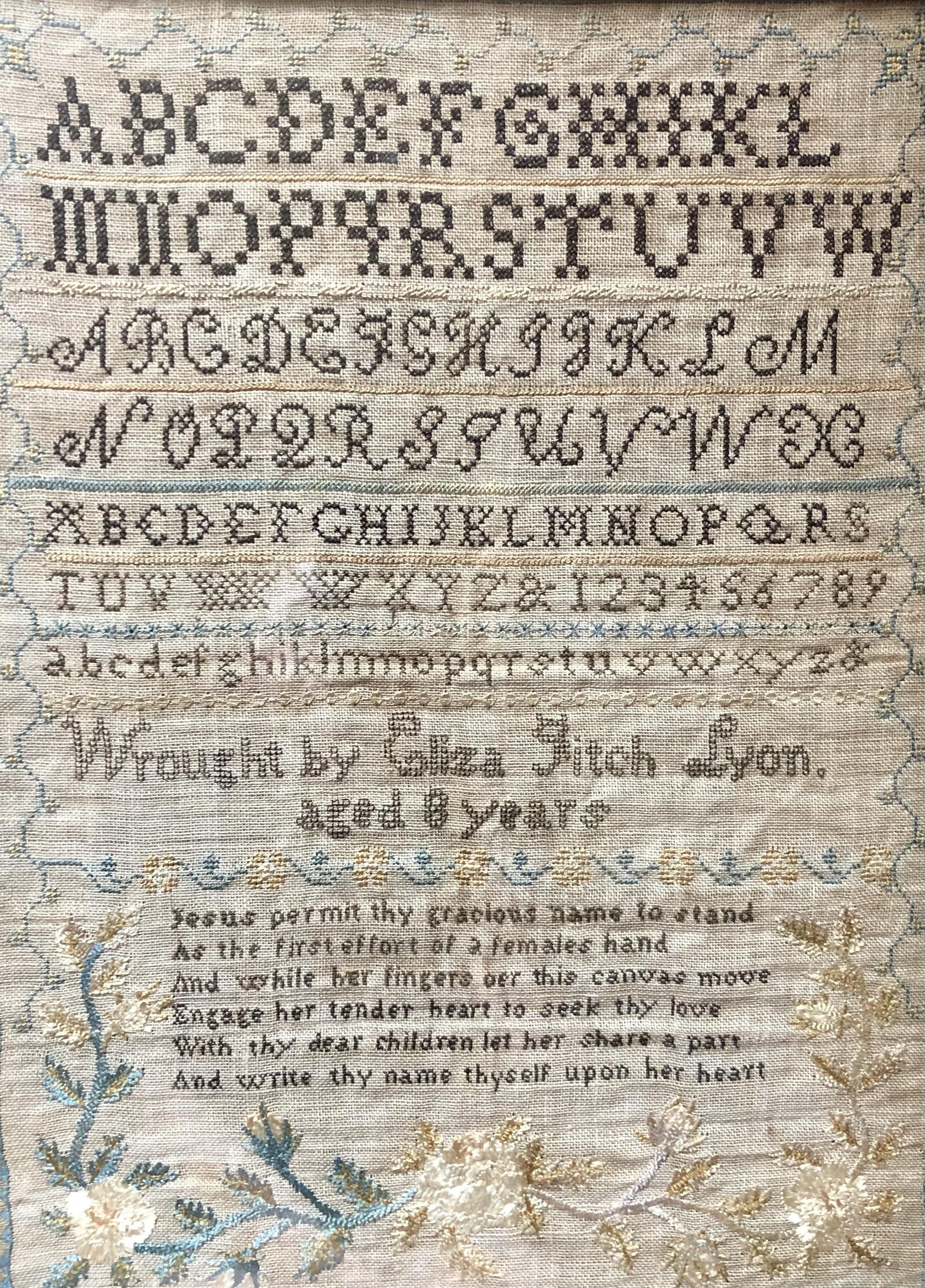

In a speech given at the Obstetrical Society of Boston in December 1910, Dr. James Lincoln Huntington railed against midwifery-- a practice he viewed as a relic of a more primitive past. Denigrating the midwife as an “evil,” “ignorant,” and dangerous woman governed by superstition as opposed to science, Dr. Huntington advocated for new regulations and laws to curtail midwifery in Massachusetts. Huntington's vitriol against midwifery is representative of a larger movement in late 19th- and early 20th-century medicine to replace independent female caretakers with male “professionals,” but sorely downplays the essential roles midwives held for centuries, particularly in New England. One of the earliest European settlers to arrive on the Mayflower in 1620 was a midwife, and Huntington’s ancestors in western Massachusetts greatly depended on midwives.

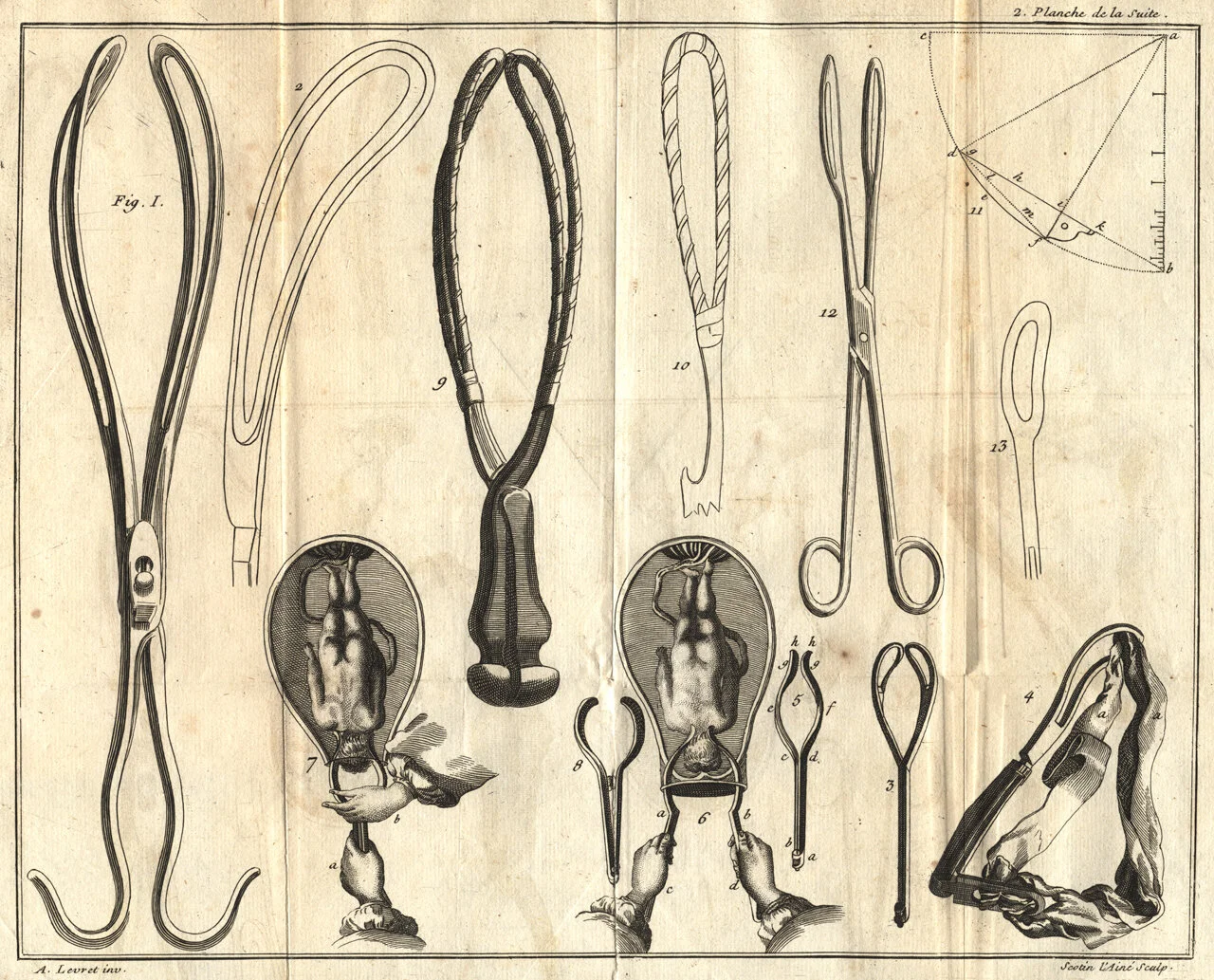

Elizabeth Porter Phelps’ diary is peppered with accounts of midwife-assisted deliveries. In early August of 1772, Elizabeth detailed her own experience. After Elizabeth “perceived some alteration,” Charles sent for Mrs. Elizabeth Parsons Allen, a midwife in Northampton who throughout her career oversaw more than 3,000 births across Hampshire county, and “just six minutes before six in the morning,” little Charles was born. In August of 1803, Elizabeth wrote to her daughter describing the delivery of her daughter-in-law, Sally, “One more birth has been in this house… I feel as if my head was turned.” When Sally began to feel contractions, Charles Phelps fetched Elizabeth’s friends, Penelope Gaylord and Dorothy Warner, and the midwife Mrs. Eunice Allen Breck, Elizabeth Allen’s daughter. Unless a doctor was called in for an emergency operation, birth remained a strictly female affair; with the women attending often astutely aware of the laboring woman’s pain. Betsey’s difficult delivery of her son, Theodore, in February 1813, for instance, required multiple healers, and thus a male physician, Dr. Osborn, was present. Dr. Osborn arrived with “instruments of dissection,” and collaborated with the midwife to ensure the safe delivery of the child.

Midwifery also held an important societal role as midwives were often expected to uncover the identity of the father-- an answer obtained during the height of labor pains to ensure honesty. This information was vital to determine the child’s future source of financial support, and midwives often testified in court cases. A midwife’s testimony won Hadley resident Mirian Pierce alimony from the alleged father of her child, Samuel Cooke II, despite his vehement denials. Cooke was ordered to provide “35 pounds, 13 shillings, and 6 pence for maintenance of the child to date” and to pay for Mirian’s legal fees. Cooke was also mandated to pay a weekly forty shillings and continued to do so for seven years.

Most towns, especially rural communities, had at least one midwife. Midwifery afforded a woman a stable income and a decent amount of status in her community and was a tradition typically passed down through generations. In Hampshire County, Elizabeth Allen gave her medical textbooks, sidesaddle, and personal knowledge to her daughter, Eunice. The intergenerational nature of the position partially accounts for the dominance of midwives as opposed to doctors in the field of childbirth, as these women simply had more experience. Prominent Maine midwife Martha Moore Ballard, living in Augusta from 1778-1812, delivered around 1,000 babies and was much esteemed in her community. Ballard did not deliver her first child in Maine until the age of forty-three, but in her hometown of Oxford, Massachusetts Ballard witnessed many births conducted by older women and thus gained vital experience. Ballard also came from a family with a strong medical background-- an uncle was a doctor, and both of her sisters married doctors. In Ballard’s meticulous records she only called for a doctor twice in her career. Male doctors were not necessarily more competent in obstetrics than female midwives. In fact, Ballard noted numerous errors of the celebrated Dr. Benjamin Page, who arrived in Hallowell in 1791-- a testament to her greater knowledge. Ballard described one such incident when an elite family insisted on having a doctor present during their daughter Hannah Sewall’s delivery.

They were intimidated & Calld Dr. Page who gave my patient 20 drops of Laudanum which put her into such a stupor her pains (which were regular & promising) in a manner stopt till near night when she pukt & they returned & shee delivered at 7 hour Evening of a son her first Born.

Ballard also wrote of another time when one woman giving birth “was delivered of a dead daughter on the morning of the 9th instant, the operation performed by Ben Page. The infants limbs were much dislocated as I am informed." And later described Dr. Page as a “Poor unfortunate man in the practice. Whether male or female, experience was the determining factor in a midwife’s success; even so, Martha Moore Ballard remains largely unknown in the local history books while Dr. Benjamin Page received much acclaim, particularly for his contributions to the field of obstetrics.

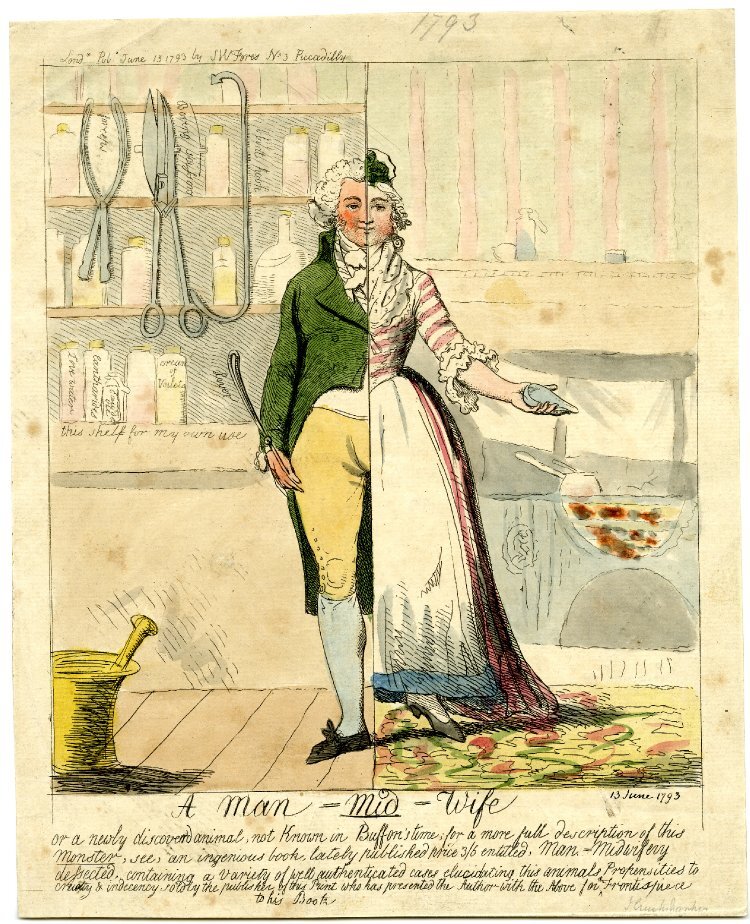

Societal obstacles for male midwifery were also present. Male practitioners of midwifery were met with fierce opposition and suspicion. After attempting to practice midwifery as a man in 1646, Francis Rayus of Massachusetts received a fine of fifty shillings and scorn from his community. The delivery room was not a welcoming realm for men; during the colonial period, midwives were often mandated to swear an oath to keep men out of the “lying-in chamber” unless necessitated by an emergency. Part of this opposition rested in the conservative desire to preserve female purity, “delicacy,” and moral standards. By the late eighteenth century, affluent women were far more likely to employ male doctors, believing modern medical science would lessen the excruciating pain of childbirth, although midwifery still maintained its primacy. These doctors opted towards privatizing the experience of childbirth: conducting deliveries in dark rooms, covering the patient in cloth, and prohibiting female friends and relatives from assisting with the pregnancy.

Male domination of obstetrics, coming to fruition in the twentieth century, was a gradual and hard-fought outcome. The growing influence of European medicine in the late eighteenth century, a result of more Americans studying abroad, resulted in a new interest in male midwifery (to be renamed obstetrics in 1828). William Shippen, an American doctor who studied abroad, returned to America mind-brimming with scientific techniques and modern technologies to aid in childbirth-- including forceps to move the fetus, laudanum to ease pain, and ergot to induce a hasty delivery. Shippen became the first man to teach midwifery in American medical schools in 1762 and thus began his lifelong crusade to legitimize obstetrics. Male obstetricians attempted to recast childbirth as a process requiring highly skilled medical intervention-- care only trained male doctors could provide. The timing coincided with the Victorian era belief that women were incapable of learning complex medical and scientific treatments. In 1848, one doctor and professor of medicine, Charles Meigsm wrote: a woman “has a head almost too small for intellect but just big enough for love.” Unsurprisingly, female midwives were excluded from advanced medical training or could not afford the same expensive new technology male obstetricians owned. In time, the chosen attendant at childbirth became inextricably linked to class. Lower-class women typically employed the cheaper expertise of the midwife, whereas upper- and middle-class women increasingly opted for a more interventionist male physician who provided painkillers as well as a certain amount of social cachet.

From the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, male obstetricians worked tirelessly to further legitimize their position and turn public favor against midwives, exploiting women’s fears of childbirth and midwives’ often foreign backgrounds. The presence of midwives in medicine posed a problem for male obstetricians: non-traditionally educated immigrants and black women successfully performed many of the same tasks as male obstetricians, suggesting that childbirth did not require some occult medical knowledge to be safe and successful. Prominent obstetrician Joseph B. De Lee even accused midwives of delaying the advance of obstetrics, insisting, “as long as the medical profession tolerates that brand of infamy, the midwife, the public will not be brought to realize that there is high art in obstetrics and that it must pay as well for it as for surgery.” Clearly, De Lee was partially motivated by financial incentives and the boost to his field’s prestige at the fall of midwives.

Dr. James Lincoln Huntington, the founder of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington House, was among the most vocal of these male obstetricians. In an essay and speech Huntington co-authored with Dr. Arthur Brester Emmons at the Boston Obstetrical Society meeting in December 1910, “A Review of the Midwife Situation,” the two men condemned midwifery. The doctors suggested policy changes to prosecute midwives more easily in Massachusetts and to strip them of their right to practice. Huntington and Emmons both reiterated De Lee’s assertion of the strictly scientific nature of obstetrics, “Bacteriology, antiseptic and aseptic surgery have put obstetrics on an entirely different basis, raising it to the position, sociologically at least, of the most important branch of surgery.” The men did not veil their contempt for independent female medical care that midwifery entailed, promoting instead “the efficient trained nurse of to-day, acting in harmony with the doctor, who carries the responsibility.” When discussing midwives in Germany, male obstetricians also suggested their hesitancy about trusting women’s ability to safely treat patients:

In the first place, one observing the work of the midwife in the confinement wards is struck by her lack of what is known as the aseptic conscience; that is, the knowledge that she is or is not surgically clean. After faithfully scrubbing her hands for the allotted fifteen minutes she will unconsciously touch something outside of the sterile field and continue as if surgically clean… But if the midwife makes these breaks in the hospital under the eyes of her instructor, and in ideal surroundings for surgical cleanliness, how much more likely will she be to fall into careless ways when out alone in a peasant’s house?

The men instead hailed Ireland’s system of midwifery, where midwives acted under the close supervision of “medical men,” as a paradigm to be emulated in Massachusetts. The men quoted an anonymous Massachusetts physician who wrote in 1802 as another authority on the matter:

As medical science has im[proved], it seems at last to have been settled that physicians regularly educated could alone be adequate to the exigencies of obstetric practice… Among ourselves, it is scarcely more than half a century since females were almost the only accoucheurs. It was one of the first and happiest fruits of improved medical education in America that they were excluded from the practice.

Xenophobia was perhaps another source of these men’s anxiety towards midwifery, as they specifically blamed the “midwife-habit” on “the mighty river of emigration which has swept into this country within the last half-century.” The two doctors were especially concerned about the lack of collective public disapproval of the practice of midwifery, “What we must first do is to arouse public sentiment, and first of all, we must have the enthusiastic support and united action of the medical fraternity.” In the conclusion of this speech the men verbally attacked the midwife once more, describing her as “ignorant, half-trained, often malicious,” and insisting that, “women and infants pay for this “freedom” in deaths, unnecessary invalidism, and blindness. This reference to deaths is another critical factor in the attack on midwives by male obstetricians. At a time when high infant mortality rates in the United States were being questioned, obstetricians were eager to shift the blame from their still relatively new branch of medicine to midwives who lacked the same ability to defend themselves.

Sources:

Huntington, James Lincoln, and Arthur Brewster Emmons. “A Review of the Midwife Situation.” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 164, no. 81 (1911).

Miller, Marla R. Entangled Lives: Labor, Livelihood, and Landscapes of Change in Rural Massachusetts. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019. =

Schrom Dye, Nancy. “History of Childbirth in America.” Women, Sex, and Sexuality, Autumn, 6, no. 1 (1980): 97–108.

Sullivan, Deborah A. “The Decline of Traditional Midwifery in America.” Essay. In Labor Pains: Modern Midwives and Home Birth, edited by Rose Weitz, 1–22. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988.

Thatcher Ulrich, Laurel. “‘The Living Mother of a Living Child: Midwifery and Mortality in Post-Revolutionary New England.” The William and Mary Quarterly 46, no. 1 (January 1989): 27–48.