A Closer Look at the Life of Elizabeth Pitkin Porter

Elizabeth Pitkin Porter, hailing from a prominent family in Connecticut and married into the wealthy Porter family of Hadley, was a woman of high stature and importance in the community. Pious and deeply caring, she attended church regularly, taught her grandchildren to read and write, and often traveled across western Massachusetts to support ill relatives and friends. Elizabeth’s life, however, had a darker side-- an open secret amongst her friends and family. Elizabeth suffered from anxiety attacks, crippling episodes of depression, and, ultimately, an all-consuming addiction to opium. Contrary to popular belief, Elizabeth’s mental health struggles and exposure to opium were ongoing and long predated her husband’s tragic death in the Seven Years’ War. Feelings of isolation and loneliness plagued Elizabeth through early marriage, motherhood, and widowhood; finding a cure became an ongoing and often fruitless crusade.

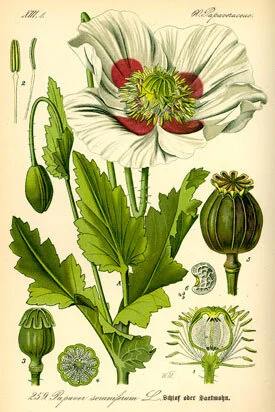

In 1742 Elizabeth Pitkin left her childhood home in East Hartford for Hadley to marry Moses Porter, leaving behind many friends and family members. Over the next few years, Elizabeth experienced extreme anxiety-- perhaps a response to the dramatic change in her social environment. By February 1747, shortly before becoming pregnant with her daughter, Elizabeth received a prescription for an opium-based drug after a visit with the family doctor, Richard Crouch. The year 1752 brought another significant change in Elizabeth’s life. The couple moved away from their house in the Hadley town center, a site of socialization and camaraderie with neighbors, to the home Moses built, two miles away from any other property, which certainly contributed to Elizabeth’s feelings of isolation. By 1753 Elizabeth was diagnosed with “hysteria” -- a catch-all term for anxious, depressed, or supposedly amoral women-- and prescribed laudanum, an alcoholic solution containing opium.

At the time laudanum was lauded as a panacea-- a treatment for both physical and mental ailments. One English physician, Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689), celebrated the drug’s versatility, “Among the remedies to which it has pleased Almighty God to give to man to relieve his sufferings, none is so universal and efficacious as opium.” Towards the end of his life, Benjamin Franklin depended on laudanum to relieve the excruciating pain from his kidney stones. Abraham Lincoln was prescribed ointments containing laudanum to counter periods of depression. While some of the drug’s negative side effects were understood-- in 1818 the American Dispensatory even warned of the “tremors, paralysis, stupidity, and general emaciation” from excessive usage-- opium addiction was never publicly recognized until the release of Thomas De Quincey’s book in 1821, Confessions of an English Opium Eater. Quincey described the drug’s potency: “[H]appiness might now be bought for a penny, and carried in the waistcoat pocket: portable ecstasies might be had corked up on a pint bottle and peace of mind could be sent down in gallons by the coach mail.” Long before Thomas Quincey’s forays with the drug, Elizabeth would succumb to opium’s intoxicating effects.

The Seven Years’ War, beginning in 1755, called Captain Moses Porter away from his home, wife, and daughter at Forty Acres. While Moses fought under Colonel Ephraim Williams at Crown Point in northern New York, Elizabeth toiled at home, raising their daughter and living in constant fear that Moses would soon die. During this time, the property’s distance from other homes became particularly unbearable for Elizabeth. One letter from Moses in July of that year reveals Elizabeth’s depressed mental state “I Received yours of the 14 of July [on] 19 of the same which was such a cordial to [me] as I had not had since I left you… You hinted something of being [alone] even in company I am very sensible of it my [self] but I believe you have a double portion of it.”

Elizabeth also experienced the stresses of war more immediately, writing to Moses about army deserters who “milk our cows devour our corn destroy our garden and are often about the house in the night.” In August, sensing depression and apathy in Elizabeth’s letters, Moses wrote: “I could have been glad to ha[ve] seen a Little more of the Hero in your letter.” Moses could not have fully understood the trials Elizabeth faced at home. Elizabeth simply dismissed his critique, insisting, “You must not expect masculine from feminine.” The couple’s correspondence, however, would soon cease. The Battle of Lake George in early September proved fatal for Moses; his sword would later be returned to a bereaved and traumatized Elizabeth.

Moses’ death inaugurated a new period in Elizabeth’s life: widowhood. Elizabeth did not remarry, continuing to raise her daughter and run the farm with the help of a distant relative, Caleb Bartlett. The diary of Elizabeth’s daughter provides insight into her life during this period, cataloging the multitude of doctor’s visits, her growing dependency on laudanum, and desperate attempts to battle depression and addiction.

A typical treatment for depression at the time included regimented exercise and outings. Elizabeth rode horses and visited watering holes supposedly blessed with healing properties throughout western Massachusetts and northeastern Connecticut. During one such trip Elizabeth wrote to her daughter: “How long I shall be upon my Jorney I cant tell, I shall endeaveur to follow the directions of Providence for the recovery of my health, I hope I aint worse then when I left you. I wish I may return in a Comfortable state of health.” Her mention of “Providence” reflects the important role religion held in her life. While Elizabeth saw her faith as a path to heal, and the church provided structure and neighborly support, oftentimes the church was not beneficial for women with chronic depression. Women who were unable to overcome prolonged periods of depression could be perceived as morally repugnant and, consequently, often masked symptoms of depression to avoid public scrutiny.

When non-pharmaceutical methods failed, doctors often opted for laudanum to treat depressed or “hysterical” women. During the 18th century, opium was especially popular in treating medical issues specific to women. In his Treatise on Opium written in 1753-- the same year Elizabeth received a prescription for laudanum-- Dr. George Young advocated the use of opium to curb nausea during pregnancy. The Married Woman’s Private Medical Companion, written by A.M. Mauriceau in 1847, suggested opium to relieve menstruation cramps:

Let the patient have near her a few pills, consisting of opium… She is to take one of these pills the moment the pain attending this discharge comes on. A pill may be taken every hour till the pain ceases: more than two will seldom be required; yet they must be taken in quantities sufficient to mitigate the pain.

Elizabeth also suffered from physical problems, including “Rhumatizm,” which were commonly treated with laudanum as well. The “cure” for many of Elizabeth’s physical ailments was in fact the source of her pain and, like many chronic opioid users, Elizabeth suffered from muscular weakness, impaired memory, apathy, and cessation of the menses. Attempts to quit were still made, especially with encouragement from family and friends, but, even so, Elizabeth remained in the depths of severe addiction. One diary entry from Elizabeth’s daughter in 1784 offers a glimpse into the continued presence of opium in her life— even at the age of sixty-five. Her daughter wrote: “Old Mrs. Alexander came here with view to persuade my mother to leave off taking opium but in vain-- she took it before night the next day.” Elizabeth died in 1798 at the age of seventy-nine; a victim of a medical practice that had yet to grasp the full effects of chronic opium use.

Sources:

“ATrain Education.” What Precipitated the Opioid Crisis? ATrain Education. Accessed July 20, 2021.

Crandall, Russell. Drugs and Thugs: The History and Future of America's War on Drugs. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021.

Mauriceau, A M. The Married Woman's Private Medical Companion. New York, 1847.

Mays, Dorothy A. Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2004.

Pendergast Carlisle, Elizabeth. Earthbound and Heavenbent. New York, NY: Scribner, 2004.

Phelps, Elizabeth Porter. The Diary of Elizabeth (Porter) Phelps, edited by Thomas Eliot Andrews with an introduction by James Lincoln