Educational Endeavors

One of the many things that links the disparate branches of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington family was their deep commitment to education, both for themselves and for others. Across generations and geography members of the family founded, worked at, and donated to schools all over the country, some of which still stand today. From gendered boarding schools to vocational schools for Black and Native Americans to the local day school, the family exhibited a real investment (in every sense of the word) in education.

The family’s involvement in education can be traced back to some of the very first settlers of Hadley. Elizabeth Pitkin Porter was remarkably well educated for the mid-eighteenth century and passed such qualities down on to her daughter, Elizabeth Porter Phelps, whose ability to read and write permitted her meticulous diaries which have, in turn, been integral in shaping the Museum and the stories it tells. There are several accounts, too, of Elizabeth Porter Phelps doing as her mother did and educating the next generation of women, or, as Elizabeth Pendergast Carlisle puts it, “teaching the skills necessary to become the industrious wives of farmers, educated women, and God-fearing members of the pious community that she strove to perpetuate.”

The man whom Elizabeth Porter Phelps married, Charles Phelps, was perhaps the first to formally engage with institutional education, serving as one of the Trustees of local Hopkins Academy for over thirty years. Charles’s younger brother Timothy also married the younger sister of Emma Willard, the beginning of a fruitful relationship between the Emma Willard School, then called the Troy Female Seminary, and the family.

Portrait of Elizabeth Huntington Fisher

Elizabeth Huntington Fisher, the daughter of Elizabeth Whiting and Dan Huntington, was among the first students to attend the now-prestigious school in Troy, New York. Her sisters soon followed in her footsteps, and Huntington Fisher even returned to the school after she graduated to teach.

Like his father in-law, Dan Huntington dedicated his time to the local school, Hopkins Academy. He was its principal for three years (1817-1820) but a Trustee for much longer, serving in the role until he died in 1864.

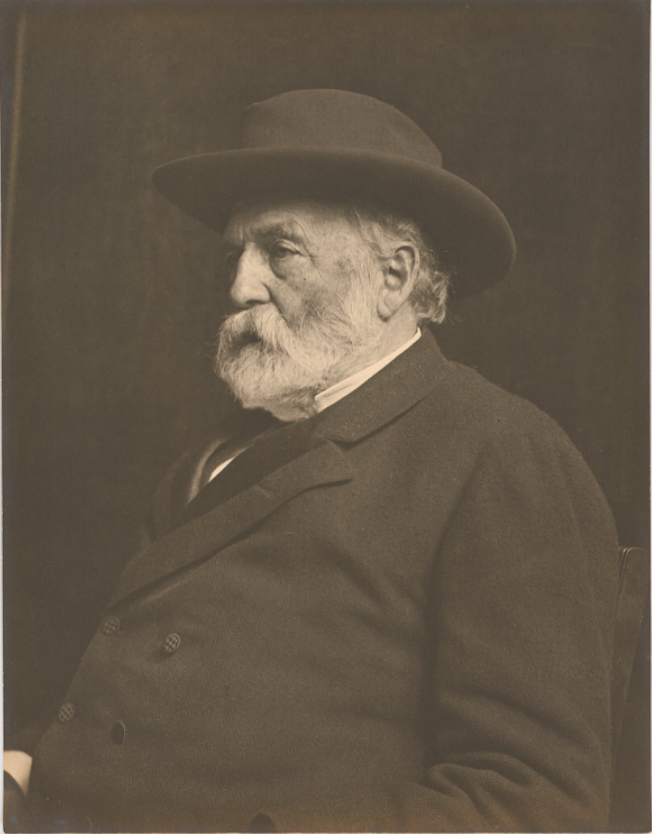

Portrait of Reverend Frederic Dan Huntington

Elizabeth and Dan Huntington’s youngest son, the Reverend Frederic Dan Huntington, was active in the educational world as well. Founder of the St. John’s School in Syracuse, New York in 1869, he endeavored “To rear men well-built and vital, full of wisdom… full of energy… full of faith.” Even though the school still exists today, Frederic Dan Huntington might have been found lacking in the execution of his goal, as even the school’s own website conceded that “dwindling enrollment left the school on the verge of closing” less than twenty years after it opened. Under new management, the school rebranded itself into a military academy and thrived well into the twentieth century.

Portrait of Arria Sargent Huntington

Frederic Dan’s daughter, Arria Sargent Huntington, was also prominent in Syracuse for her contributions to education as well as the advancement of various other social causes. As well as founding hospitals, shelters, and working associations for women, Arria served as the School Commissioner for the Syracuse Department of Education; a great achievement, but one especially remarkable given the number of women in leading administrative positions at the time. During her six-year tenure from 1897 to 1903, Arria also headed and participated in a number of School Committees that kept the educational system well-serviced and functioning.

Photo of James Otis Sargent Huntington

Frederic Dan’s son, James Otis Sargent Huntington, was perhaps foremost among the family in the creation of schools. Founder of the Order of the Holy Cross, which describes itself as “An Anglican Benedictine Community of Men,” his religious work coincided with his commitment to education. Under the direction and with the help of James O.S. Huntington, the Order founded two schools which are still educating students to this day, though the Mission in Liberia and a “Home for Wayward Girls” in Tarrytown, New York cease to operate. One of the schools founded by James O.S. Huntington can be found (albeit under a slightly altered name) in Sewanee, Tennessee. Originally called the St. Andrew’s School, it was created in 1905 to serve “deserving mountain boys” and interrupt the “cycle of poverty” in a historically underserved part of the country. Though the school has undergone many alterations, including a stint as a military academy, it has remained true to its religious roots. The Kent School, also founded by Huntington several hundred miles away in Connecticut, shares many characteristics with that of Sewanee. Founded with the help of James O.S. Huntington in 1906, it too retains its affiliation with the Episcopal Church and upholds its founders’ emphasis on spiritual education. Shared by the two schools, too, is a costly price of attendance: upwards of $50,000 for boarding students in 2021.

Roger Fenn, courtesy of https://www.fenn.org/page.cfm?p=516

These two were not the only private schools founded by the family. In 1929, Roger Fenn, descendant of Elizabeth Porter Huntington Fisher, founded the private, all-boys elementary institution called the Fenn School. Located in Concord, MA, its goal was to give “each boy…guidance and support in accepting a continuing and growing responsibility to himself, to his fellow students, to his school, and to the larger community.” In reading the educational missions of the various schools founded by the family, the common goal of creating better citizens can be easily traced. However, though they might have been noble in their goals, the demographics of contemporary and current students likely skew towards white and wealthy, a fact that should be noted in a discussion about the family’s educational philanthropy.

Portrait of Mary Otis Lincoln Sargent

These were not the only members of the family to have worked at a private elementary school. At the Derby Academy, the oldest coeducational educational institution, you could find Mary Otis Lincoln Sargent teaching and her father as headmaster. It was there where Mary met the sea captain Epes Sargent V, the father of one of her students and her soon-to-be husband.

Photo portrait of Collis P. Huntington

On the outer branches of the family tree lies Collis Potter Huntington, second cousin once-removed of Dan Huntington and founder of the Central Pacific Railroad. A tycoon of transportation and one of America’s “Big Four,” C.P. Huntington was instrumental in the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad and left a visible imprint on the nation in the form of railways and spikes. Lesser known, though, is the impact he made through his educational philanthropy. Collis P. Huntington has been described as “an ardent abolitionist and a supporter of African American education,” and his donations to the Virginia-based Hampton Normal and Industrial School for Negroes and Indians and the Tuskegee Institute reflect that. The Hampton School, now called Hampton University and an HBCU, was where Booker T. Washington got his start and was created with the goal of giving Black and Native Americans “Practical experience in trades and industrial schools.” Both of the schools which C.P. Huntington patronized are credited with training “’an army of black educators’” that spread out across the country.

The particular brand of education that Collis was endorsing, however, should be analyzed. As one account notes, “Booker T. Washington’s projects, and schools that followed his principles were funded by wealthy, white, northern donors… They approved of his approach of not directly confronting racial inequality but ‘uplifting the people’ through education.” Though Washington was undeniably undertaking important and influential work, it emphasized uplifting oneself and almost tacitly absolved the systems and people that created the hurdles to self-support in the first place. Furthermore, while the scholar Paulette Fairbanks Molin notes the “pioneering model in academic instruction and manual-technical training” of the Hampton Institute, she also highlights how “The Hampton plan included now-familiar components of off-reservation boarding schools” that isolated students from their families and attempted to erase their traditions and cultures.

As mentioned above, while many of the educational endeavors of various members of the family might have been noble, they often reflect the period and their socioeconomic position: these were religious, white, and wealthy members of American society and even when they supported a cause like Black education it was only under specific terms and conditions. Less formal methods of education should also be mentioned – while historical records are forgiving for men who founded and patronized schools, there exists alongside this narrative a long history of women tutors and learners in the household that merits further exploration and discovery. Ultimately, though, it is remarkable that there existed such a strong connection between this family and the world of education, their propensity to start, fund, or work at schools spanning well over a century and across the United States.

Works Cited:

“The Art of Wealth: The Huntingtons in the Gilded Age.” Pasadena Now. January 31, 2013. https://www.pasadenanow.com/main/a-gilded-age-family-saga-new-book-provides-fresh-insights-on-huntington-familys-wealth-art-collecting-and-philanthropy/.

Baratta, Catherine. “Arria Sargent Huntington’s Curriculum Vitae.” https://static1.squarespace.com/static/53cd26f2e4b03157ad2850da/t/596fb01317bffc637c5c23c0/1500491811546/Baratta_Arria_Sargent_Huntington.pdf.

Binnicker, Margaret. “St. Andrew’s-Sewanee School.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. March 1, 2018. https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/st-andrews-sewanee-school/.

Carlisle, Elizabeth. Earthbound and Heavenbent: Elizabeth Porter Phelps and Life at Forty Acres. New York: Scribner, 2004.

“Dan Huntington.” Finding Aid, Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections. http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/amherst/ma30_odd.html#odd-dh.

“School History.” The Fenn School. https://www.fenn.org/page.cfm?p=516.

Morgan, Tina. “The Making of Manlius Pebble Hill: A Tale of Two Schools.” Manlius Pebble Hill School. http://www.mphschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Tale-of-Two-Schools.pdf.

“Hampton Institute and Booker T. Washington.” Viriginia Museum of History & Culture. https://virginiahistory.org/learn/historical-book/chapter/hampton-institute-and-booker-t-washington.

“History.” Hampton University. https://www.hamptonu.edu/about/history.cfm.

Molin, Paulette. “Training the hand, the head, and the heart: Indian Education at Hampton Institute.” Minnesota History: Fall 1988. http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/51/v51i03p082-098.pdf.

“Our History.” St. Andrew’s-Sewanee. https://www.sasweb.org/about/history.

“Our History & Traditions.” The Kent School. https://www.kent-school.edu/about/our-history-traditions.