In the Archives with Catharine Sargent Huntington

Last month, the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum interns and staff made a visit to the Special Collections and University Archives (SCUA) at the W. E. B. Du Bois Library of UMass Amherst to take a look at the PPH Family Papers. We turned the pages of Elizabeth Porter Phelps’ memorandum book, the scrapbooks and journals of museum founder James Lincoln Huntington, and the recent acquisition of Charles Porter Phelps' "adventures" and shipping receipts from his time as a merchant in Boston from 1799-1816. The finding aid can be viewed on their website, here.

Our discussion with Aaron Rubinstein, Head of the Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, and Danielle Kovacs, Curator of Collections, related the donation of the PPH Family Papers from the Porter Phelps Huntington Foundation Inc. to SCUA, in 2021. A large number of boxes contained the papers of Catharine Sargent Huntington, which had previously been placed on deposit and processed by archivists and staff at Amherst College. Over the course of 2022, Cheryl McNeill Schwab at UMass assessed the work that had already been done and, realizing there were still boxes that had not yet been sorted, described and processed, saw the need to create a more comprehensive finding aid to better integrate them and ensure that interested visitors might have easy access.

Two PPH interns were invited behind-the-scenes to assist in the sorting of these boxes. The discoveries we made in the archiving process – though not all revolutionary – were at once amusing and insightful, and did much to flesh out the rich stories we have already collected about this incredible woman.

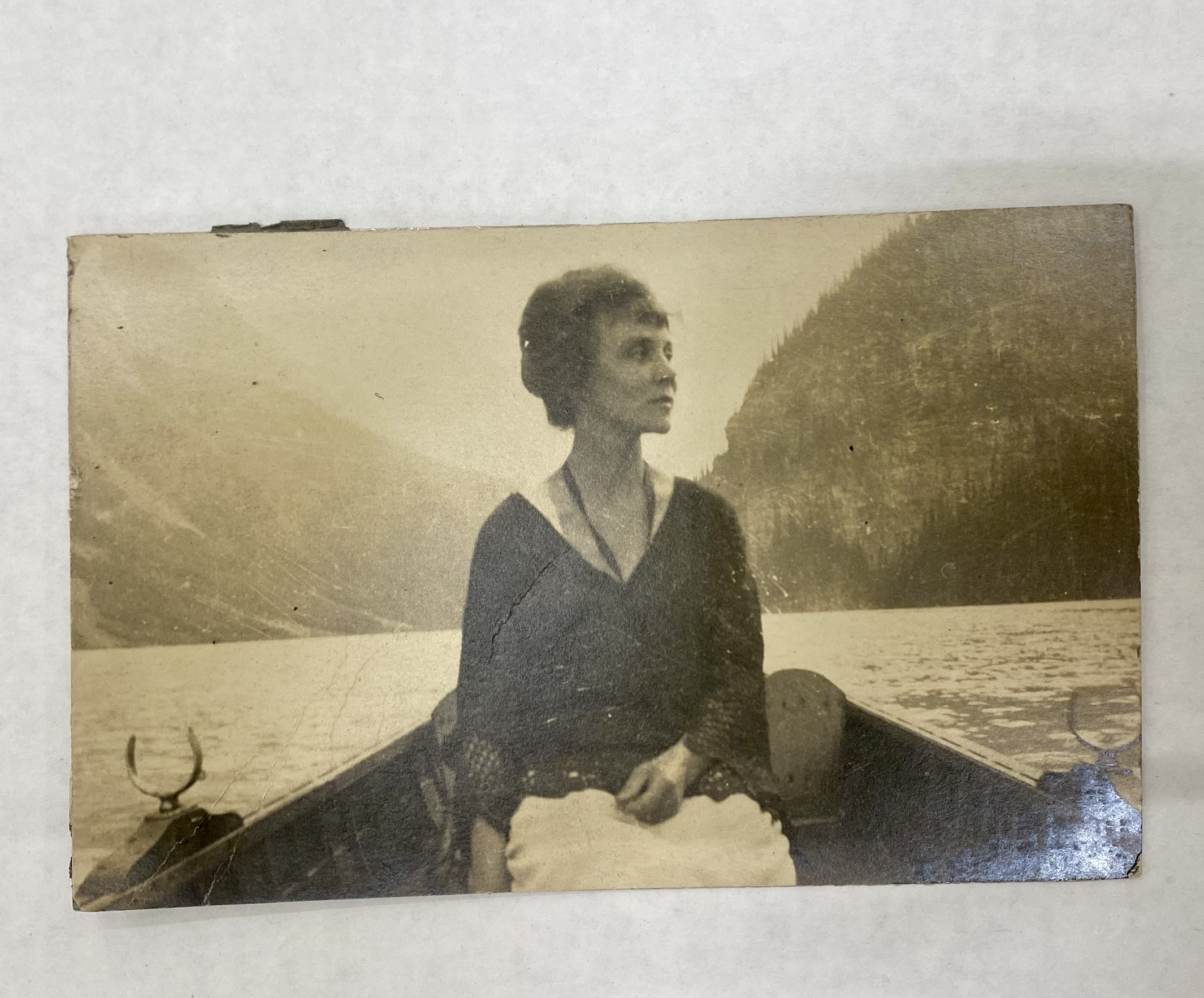

As was written in a 2016 PPH blog post linked here, “Catharine Sargent Huntington was a prominent actress, activist, and Boston society member. The only daughter of George Putnam Huntington and Lilly St. Agnam Barrett Huntington to survive past infancy, Catharine was born on December 29, 1887 in Ashfield, Massachusetts and grew up in Hanover, New Hampshire.” Over the course of her 100 years of life, she “influenced and inspired those interested in theater and justice in the Boston area and beyond”, traveled around the world, aided in local war reconstruction efforts, fostered important relationships with family and fellow creatives, and in the process amassed a significant collection of papers and other artifacts that have proved to be invaluable in our family research efforts.

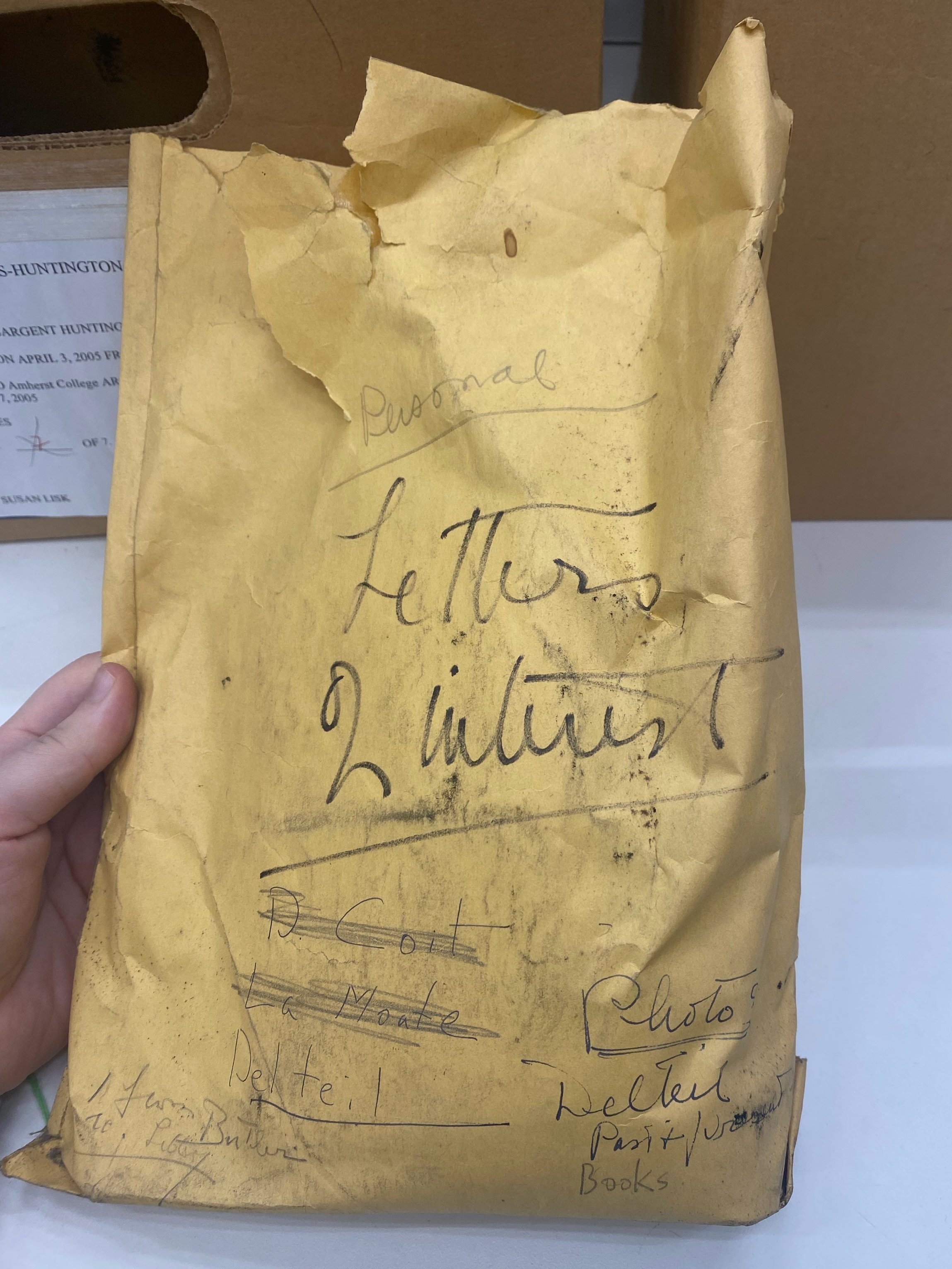

According to the SCUA webpage, Catharine’s papers span “almost a century from the late 1800s to the late 1900s'' and include “more than 2,300 pieces of correspondence; photographs; scripts; original manuscripts of her poems, speeches, newspaper clippings; estate and will information; personal financial documents; and much other printed material and items of ephemera.” They have been organized into 5 series: Correspondence; Personal; Professional; Porter-Phelps-Huntington Foundation, Inc; and Photographs and negatives. As interns working to assess what were sometimes antiquated, complex, and stuck-together documents, sorting items into definitive categories became a challenge early on – some papers were nearly illegible, and others were clearly related to multiple series. These challenges sparked fascinating conversations with other archivists in the office, and gave us unique insight into the ethics of the very human decisions being made when documenting history.

As we lifted item after item out of old cardboard boxes and into labeled folders, much of what we found were bills, a surprising number of blank decorative cards, and letters from family and friends updating her on their travels. One such note was a postcard sent by still-living British-based artist Kaffe Fassett in 1963. His short message wishes Catharine a Happy New Year from California and features a lyrical pen drawing of what appears to be a dove, as well as a photograph of a young Fassett in front of a wall of paintings.

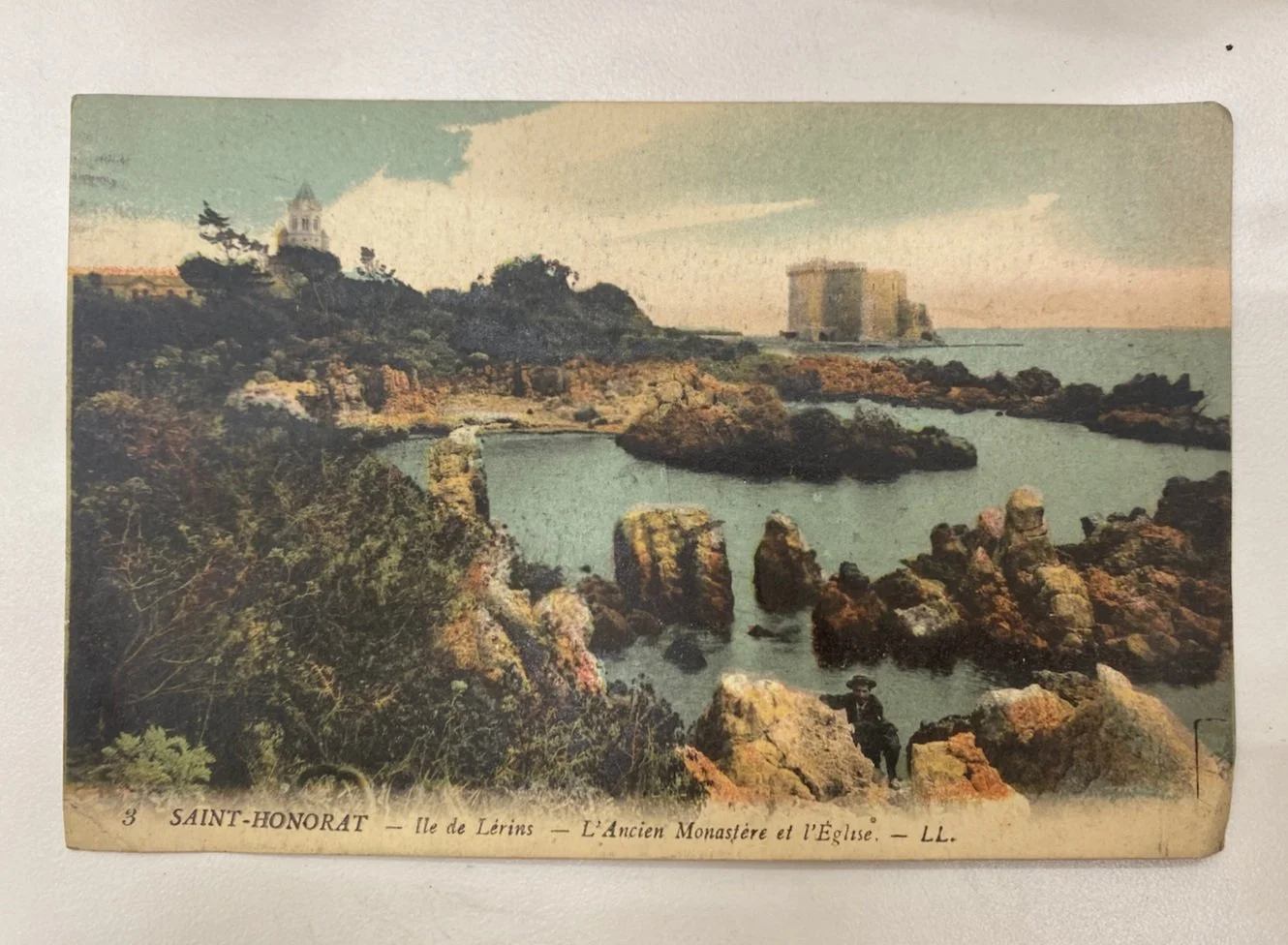

We discovered another group of postcards both sent and received by Catharine from various cities in France, written in a mix of English and French, with vibrant touristy pictures on the fronts. Paired with a stack of 2-inch wide contact prints of French architecture and countryside, there was much material evidence in these boxes of the time she spent working as a nurse’s aid with the YMCA and helping the war reconstruction effort in France between the years of 1914 to 1920.

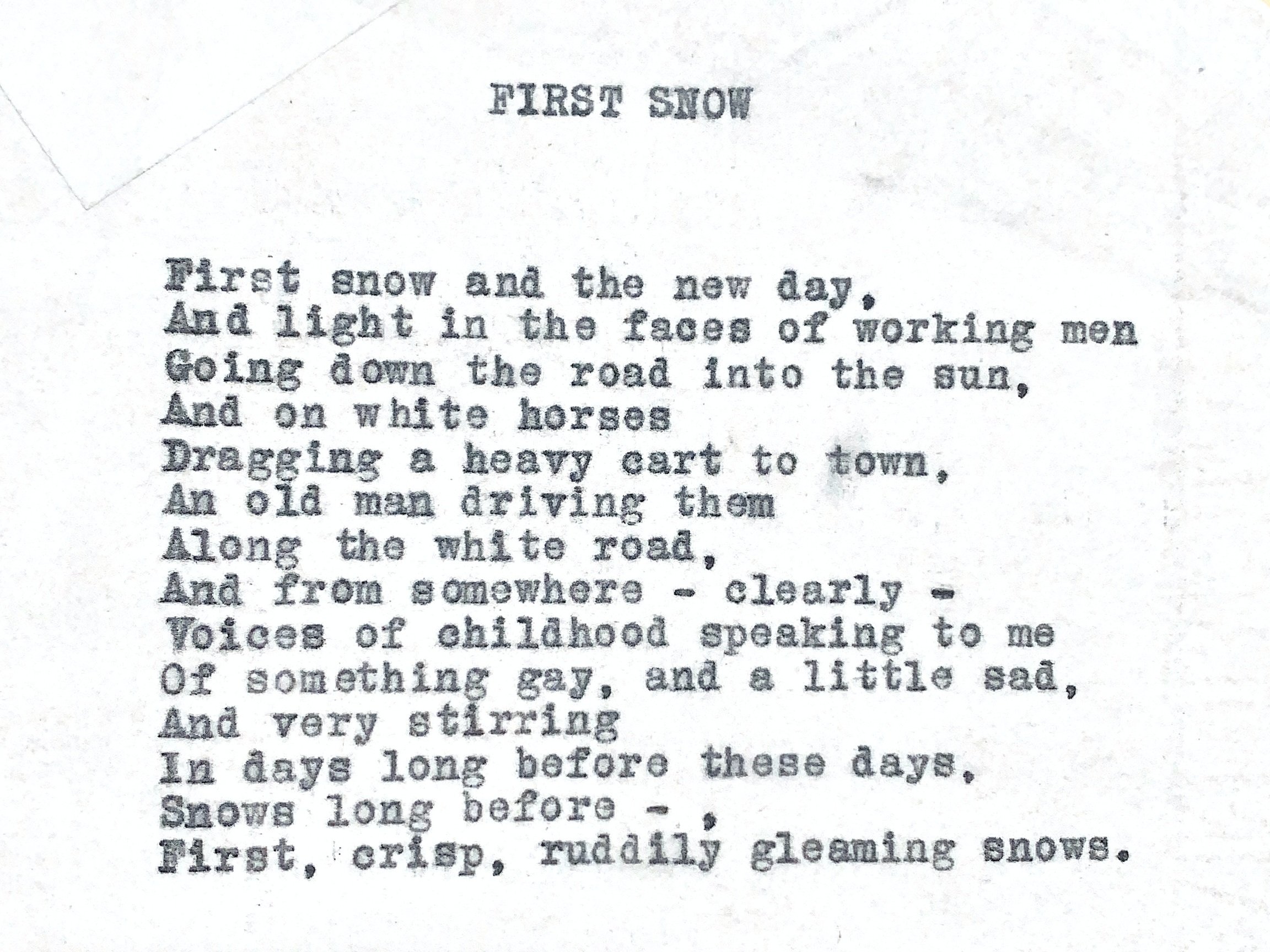

On a personal note, it was Catharine’s writing and poetry, perhaps never intended to be seen by others, that proved the most emotionally impactful, and effectively endeared me to her as a character in history. “First Snow” was one of a handful of short poems found amongst her papers, all of which describe natural scenes, daily activities, and allude to the melancholic passage of time.

My ultimate favorite find, however, was a single yellow paper with three curious lines of type. Whether this paper was used to test a new typewriter, air out frustrations, or communicate some secret code, the humor of its incoherent message took me aback – it felt surprisingly relatable. Though Catharine lived well into the 1980s, her carefully labeled black and white portraits and handwritten correspondence sometimes felt like artifacts from a very distant era. It was through the seemingly innocuous loose papers floating around archival boxes that I began to feel a stronger connection to who she was outside of her known relationships and accolades. These few intimate snippets of daily life cemented for me that there is so much still to learn about her. So many gaps and mysteries and stories that may have left no record. The sentiment of Catharine’s “I wonder” pervaded our time in the archives.

Since Catharine’s death in 1987, her papers and collections have continued to filter into the Museum, with each new letter, certificate, and piece of furniture enhancing the patchwork history of her life. The process itself of regularly receiving, processing, and sharing these artifacts reminds us that our understanding of this whole family, and the museum that tells its stories, is ever-evolving.