The Making of a Manuscript: A Look at Gladys Huntington's Editing Process From Turgeniev to The Borrowed Life

I.

“TURGENIEV: A Play in Two Acts” proclaims the cover of a typewritten manuscript in the the Gladys and Constant Huntington collection. It’s an unassuming document, the pages of which are beige and slightly worn with age. Undated and unsigned, the only hints at its provenance are the name and professional address of “C. Huntington” in London and a sheet of Putnam & Co Ltd stationery noting that the manuscript had been sent- to and from whom as of yet unknown- “with compliments.” The initials S.H. are marked in the top-left corner of the first page. In all of my research into their life in London, reading of their correspondence, and work with their notebooks, no such play has been mentioned.

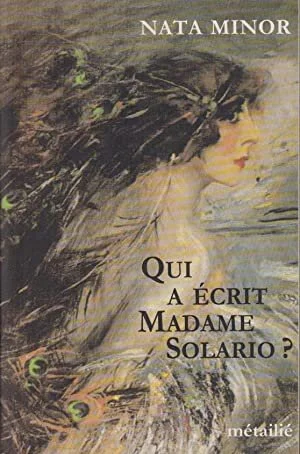

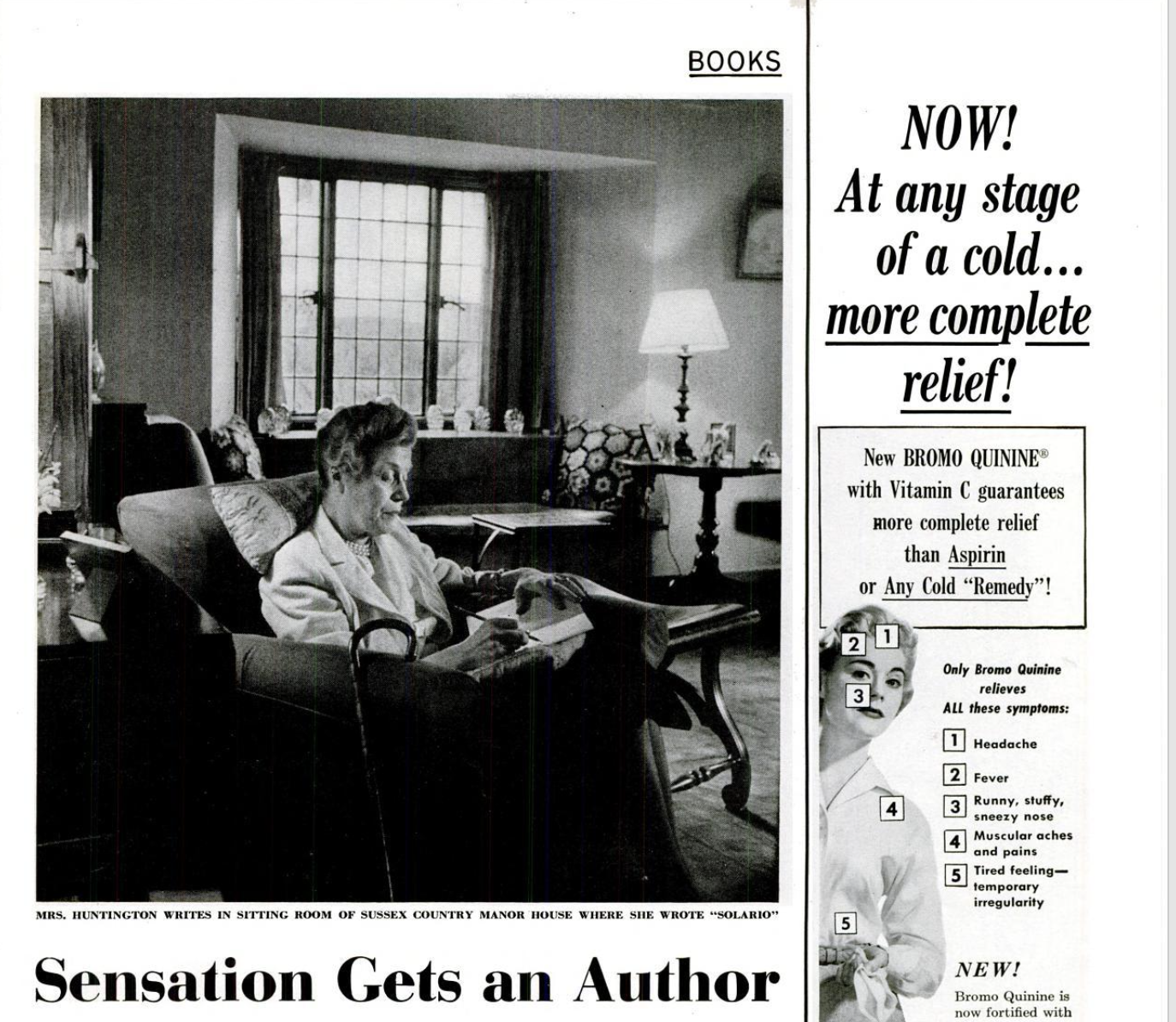

Another manuscript in the collection, printed on the same material by the same typewriting, shorthand, and duplicate company (Ethel Christian, advertised as “The Smartest in London”), is clearly identifiable as Gladys’ play “The Ladies’ Mile”, which she had written early in her life (dated 20/12/1944) and planned to adapt into a novel following the success of Madame Solario. The manuscript notes “Mrs. Huntington” at Amberley House in Sussex as the return address. This only compounds the mystery of “Turgeniev”- did Gladys write it? Did Constant, whose name is printed inside the cover? If it was sent from the Putnam offices, presumably to be reviewed by a reader, how did it end up in Constant’s or Gladys’ hands? An off hand quotation from Willa Cather’s 1918 novel My Ántonia by one of the characters suggests that the play must have been written following its publication, and the “Putnam and Co Ltd” stationery indicates the manuscript was sent at some point after 1930, when Constant secured a controlling interest in the London branch of Putnam and changed the name from G. P. Putnam’s Sons. By this time, Constant had led the London offices for over two decades (University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Archives).

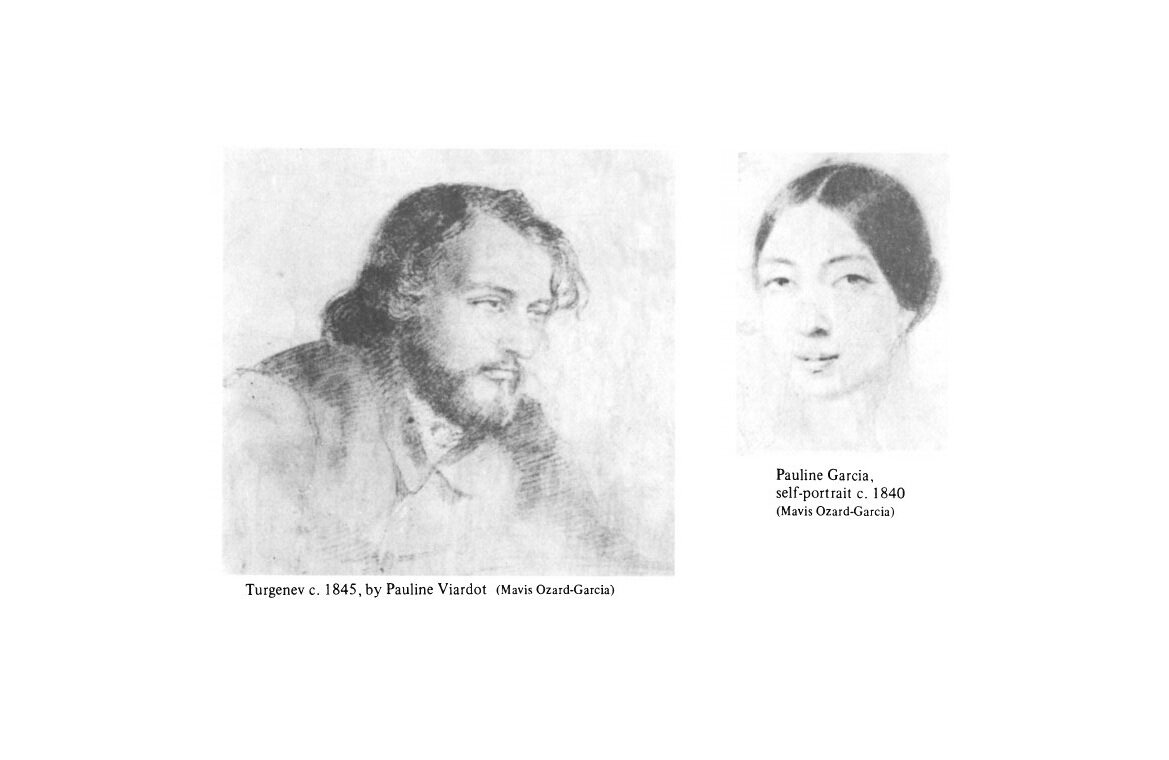

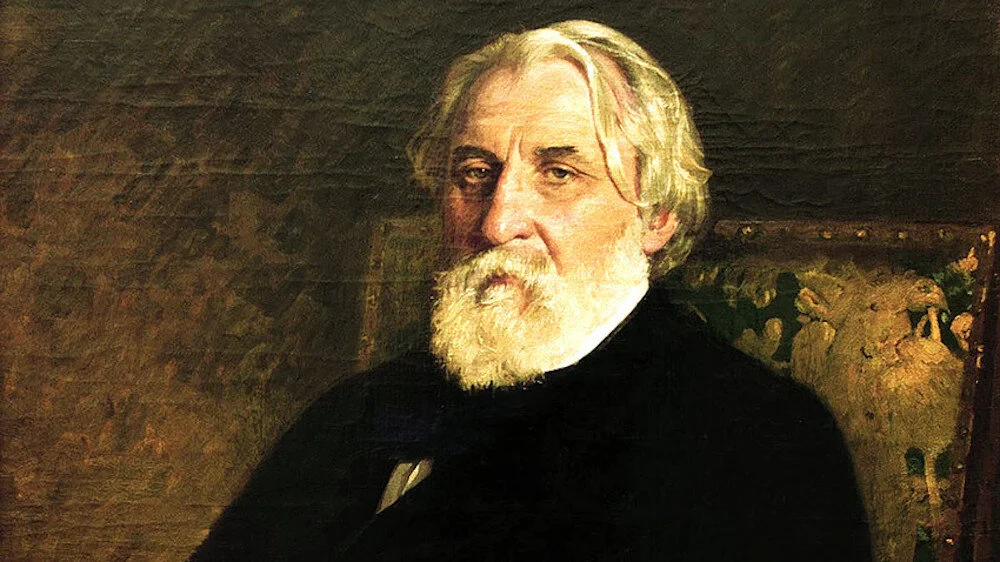

“Turgeniev'' is the fictionalized drama of the life of Russian literary giant Ivan Turgenev (the commonly accepted Western spelling of his name, curiously shunned by the author of this play). The play takes place in the early 1860’s, in the French villa of Madame Pauline Viardot, a renowned opera singer of Spanish descent. She lived there with her husband Louis, and for a time, with Turgenev, who had fallen madly in love with her after watching her perform in Russia when he was a young man (Battersby). He followed her to Europe and became a permanent fixture in the Viardot household, passionately in love with Pauline and a close companion to her husband and children. The unusual arrangement presumably worked well for the three, though it caused much dismay to the Russian public, who resented the fact that such a luminary Russian author would live beyond their national borders (Battersby).

Dostoevsky (who would later come to regard him with disdain) wrote of Turgenev upon meeting him, “A poet, a talent, an aristocrat, superbly handsome, rich, clever, educated, twenty-five years old- I can’t think what nature has denied him” (Schapiro 50). Unfortunately, their political differences would later prove an insuperable barrier between the two men, and any hope of an amicable relationship faltered. Likewise, his relationship with Tolstoy was marred by tension and political differences; at one point, Turgenev’s public dislike of Tolstoy became so extreme that it prompted a challenge to duel (an event which ultimately went unrealized) (Schapiro 172). The names of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy resonate throughout the modern day, marking their enduring literary achievements, while Turgenev’s name has faded somewhat from all but those with an express interest in Russian literature. Of course, his enormous impact on the literary and political landscape of Russia is still remembered well by his country. Turgenev’s A Sportsman’s Sketches is widely credited for bringing about the abolition of serfdom in Russia, and the Turgeniev play picks up the public’s confusion over his next novel, Fathers and Sons, which takes a more ambivalent attitude towards the future of Russia. Coupled with his relocation from Russia to France at Viardot’s behest, Turgenev’s political alliances were publicly called into question.

The front page to the Bantam Classic edition of “Fathers and Sons”, which speaks to Turgenev’s impact as a writer.

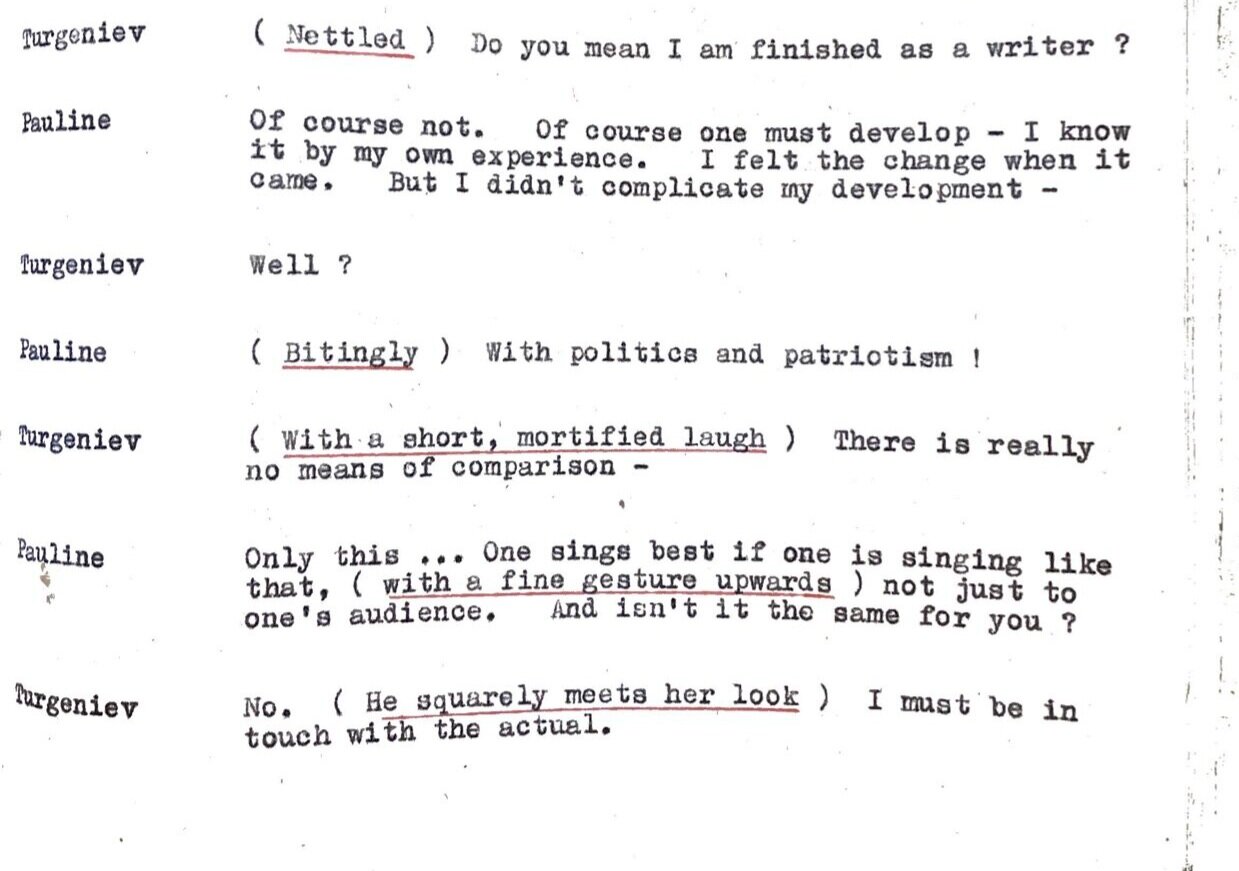

The play’s text is rife with consideration of the same questions that preoccupied the literature and life of Turgenev- whether art should strive for political or aesthetic ambitions, the literary imagination, and the destructive force of passion and love. While the play is grounded in the history of Turgenev and Viardot, the next generation of characters come from the author’s imagination. The ethereal Delphine Viardot, fictional daughter of the nonfictional Pauline, is one such character. In Countess Alexandra Tolstoy’s introduction to Turgenev’s seminal work Fathers and Sons, she quotes a remark he made to a friend: “I could never invent my characters...I could not create an imaginary type. I had to choose a living person and combine in this person many characteristics in conformity with the type of my hero” (Tolstoy viii). The author of Turgeniev seems to have picked up on his technique; Delphine is often referred to as almost a creature sprung from Turgenev’s mind:

TURGENIEV: It may be only a fancy, but sometimes I am afraid...that you enter too much into what I have imagined...My child, Delphine, it mustn’t become a spell that we will have to break. You mustn’t have your life in my imagination. (77.3.I)

❋

TURGENIEV: To tell the truth, [Bazarov] has taken on a life of his own, and now he alarms me a little- and he himself is laughing at me! That is what sometimes happens- a creature of the imagination goes forth and lives, independent of its creator!

DELPHINE, who has been sitting in an intense stillness and inner concentration, puts down her work, and gazes at him. (13.1.II)

The Frankenstein-esque undertones of this scene are unmistakable- both in the sense of Delphine and of Yevgeny Bazarov, protagonist of Fathers and Sons. Indeed, Turgenev told the same aforementioned friend, “The character of Bazarov tormented me to such an extent, that sometimes when I sat at the dinner table, there he was sticking out in front of me. I was speaking to someone and at the same time I was asking myself: what would my Bazarov say to that?” He reportedly kept notes of imaginary conversations with Bazarov (Tolstoy ix). In the second quotation, Turgeniev’s description of his relentlessly animate character is paired with Delphine’s curious reaction to it, aligning her with his literary imagination that brings characters to life.

II.

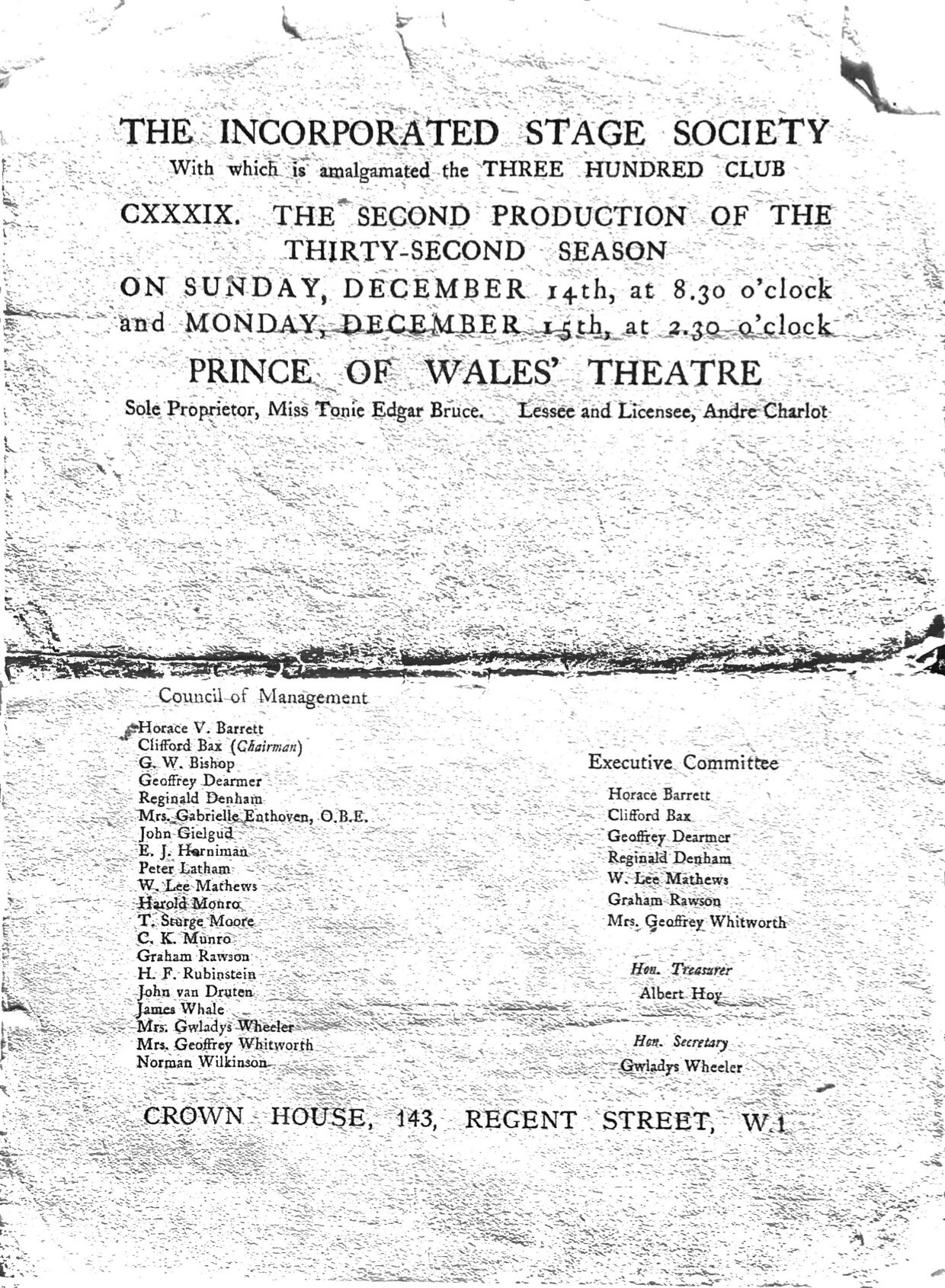

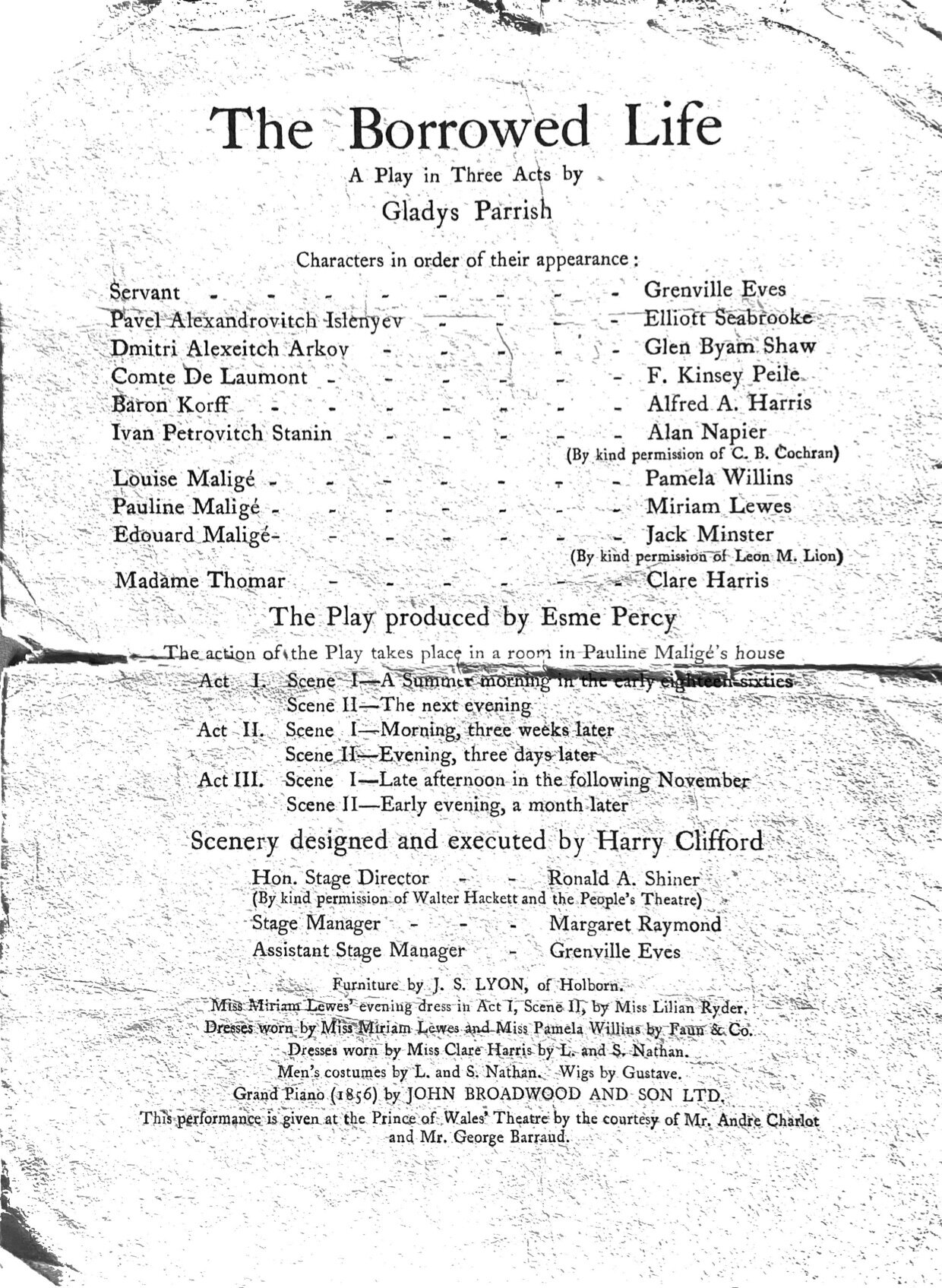

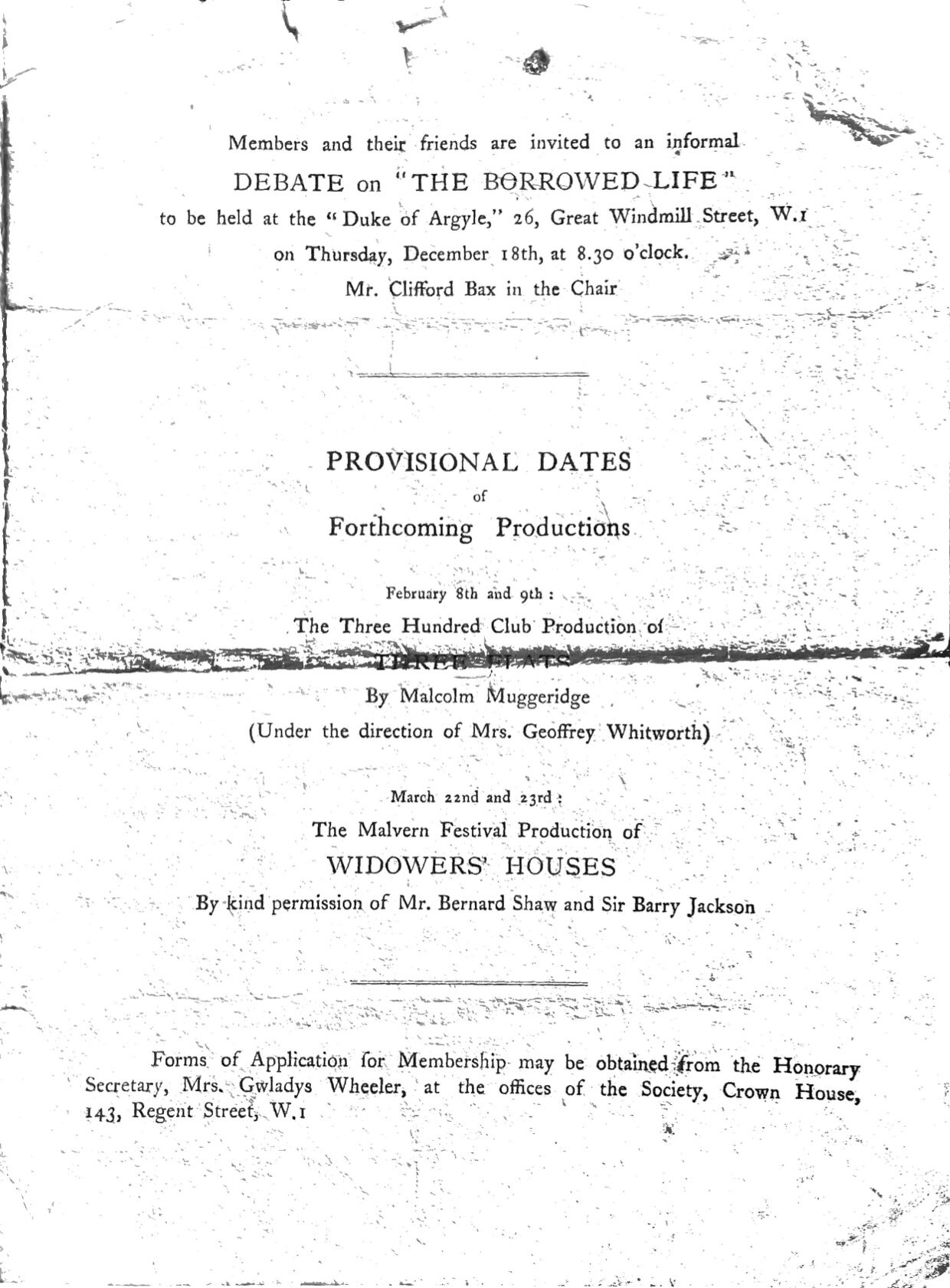

Seemingly at a crossroads with identification of this manuscript, I reached out to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where they hold a G. P. Putnam’s Sons Records collection. With so little information to go off, the archivists there were equally as stumped, but promised to look further in their records of reader’s reports and contracts to find if it had ever been published. The issue resolved itself upon the recent visit of the Urquhart-Ohno family, bearing gifts of more archival material to add to the Constant and Gladys Huntington collection. Among this new material was a playbill for The Borrowed Life: A Play in Three Acts by Gladys Parrish, produced by the Three Hundred Club. A glance through the cast list shows characters Dmitri Alexeitch Arkov, Comte De Laumont, Baron Korff, and Madame Thomar- familiar names from the character list of Turgeniev. However, the play’s namesake is missing, replaced with Ivan Petrovitch Stanin; Pauline and her husband Louis have become Pauline and Edouard Maligé; even Pavel Alexandrovitch Iretzky (who hadn’t appeared to have a real-life counterpart that I could find) was transformed to Pavel Alexandrovitch Islenyev. The addition of a third act is likewise a fascinating change. According to the playbill, Act III reportedly contains “Scene I- Late afternoon in the following November” and “Scene II- Early evening, a month later.” These are new scenes, added on to the revised Turgeniev as it transformed through the editing process to become The Borrowed Life. We don’t presently have a copy of the text of the final play or access to any of its reviews in contemporary newspapers, so the amount of change the manuscript underwent is unclear. Does Turgenev borrow the life of Delphine, using her as if a character in one of his books? Does Pauline borrow the life of Turgenev as it would have been in Russia by compelling him to move from Russia to France?

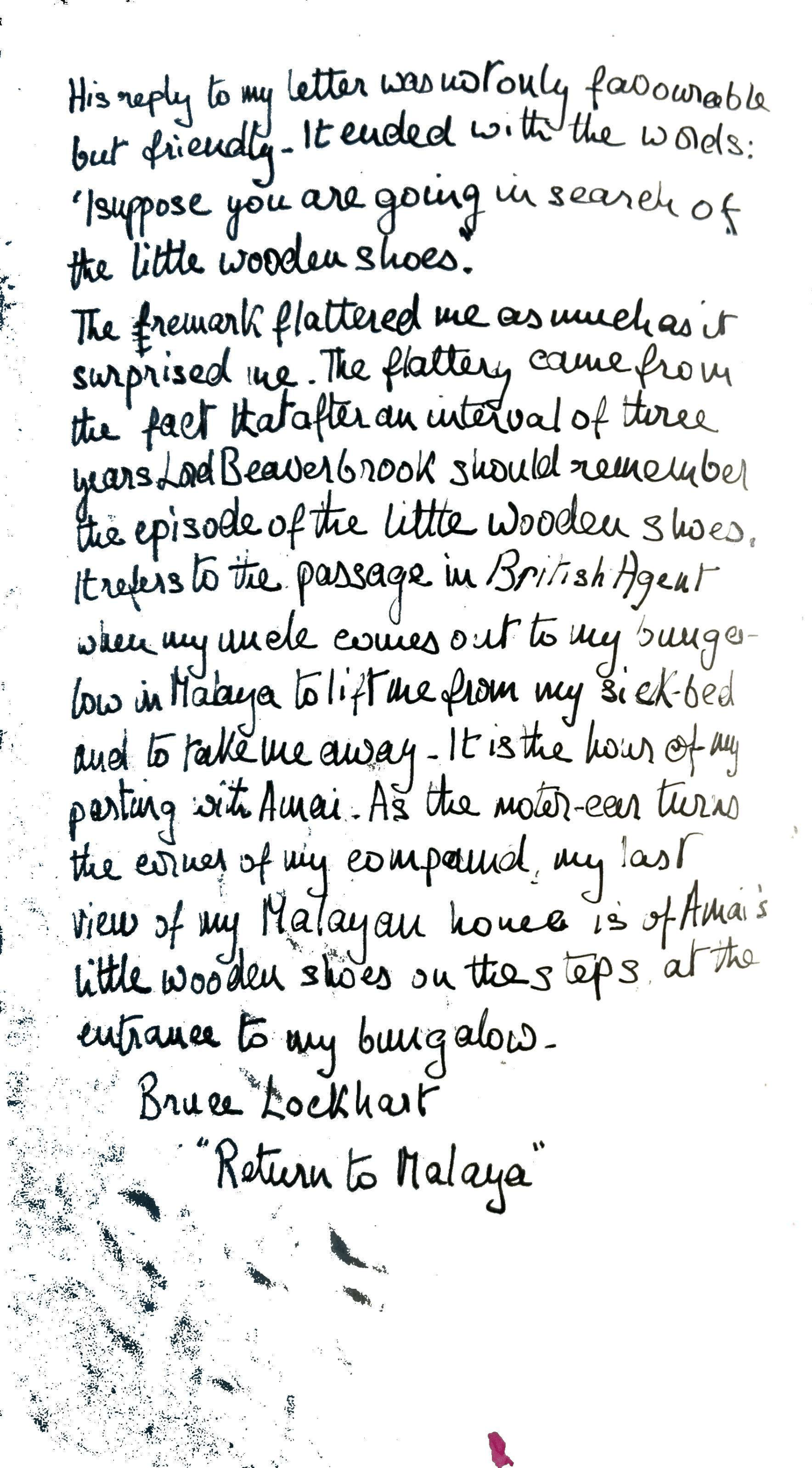

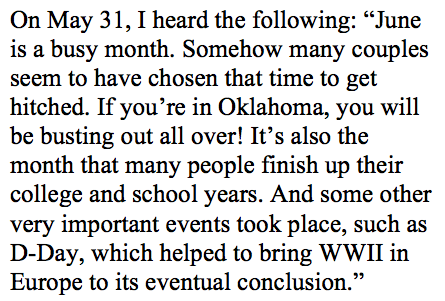

Evidently, critics and audience members still recognized the mark of Turgenev on Gladys’ play, despite her attempts to distance it from his life and history by changing the title and character names. Perhaps this is why the Sheffield Daily Telegraph in the above image notes it as being of “unusual interest.” Writing about writers and their works was and is not uncommon, and the tumultuous story of Turgenev’s life presents a particularly potent topic for a play like this one. Perhaps Gladys decided she aligned with Pauline Viardot’s idea of art as a transcendental, individual experience rather than Turgenev’s more grounded, politicized approach. In moving away from Turgeniev as a semi-fictional history of a life, she creates The Borrowed Life as a more universal exploration of the intersections between politics and art, and collective and individual loyalties, a work inspired by but not restricted by its ties to a historical reality.

Thanks to these new acquisitions from the Urquhart-Ohnos, we’re able to bear witness to Gladys’ writing process- in this case as she edits Turgeniev into The Borrowed Life. Not only does this play speak to Gladys’ development as a writer as she hones her craft through numerous drafts and changes, but it also demonstrates her growing literary sensibilities. It opens (at least in the Turgeniev version) with representatives of liberal and conservative Russian politics sent to convince Turgenev to return to Russia and interpret his work for their people; much of the play concerns itself with various interpretations of Turgenev’s work as it applies to the political landscape of Russia. As Turgeniev the character and Turgenev the man both remark, his characters and plotlines seem to come alive and require tending to. The climactic debate between Pauline and Turgenev, in which these political consequences come up against purely literary ambitions, has occupied literary critics for many centuries. In Turgeniev, or The Borrowed Life, Gladys gives it form in the words and affairs of two prominent 19th century musical and literary artists.

Bibliography

https://archives.library.illinois.edu/rbml/?p=collections/findingaid&id=943&q=&rootcontentid=90949

“Giant Actor as Turgeniev.” Sheffield Daily Telegraph [Yorkshire, England], 28 November 1930.

Schapiro, Leonard. Turgenev, His Life and Times. 1st American ed., Random House, 1978.

Tolstoy, Alexandra. Introduction. Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev, Bantam Classics, pp. i-xiii.

Waddington, Patrick. “A Catalogue of Letters by I. S. Turgenev to Pauline and Louis Viardot.” New Zealand Slavonic Journal, 1983, p. 249.