"Natural working of the carnal and unrenewed heart"

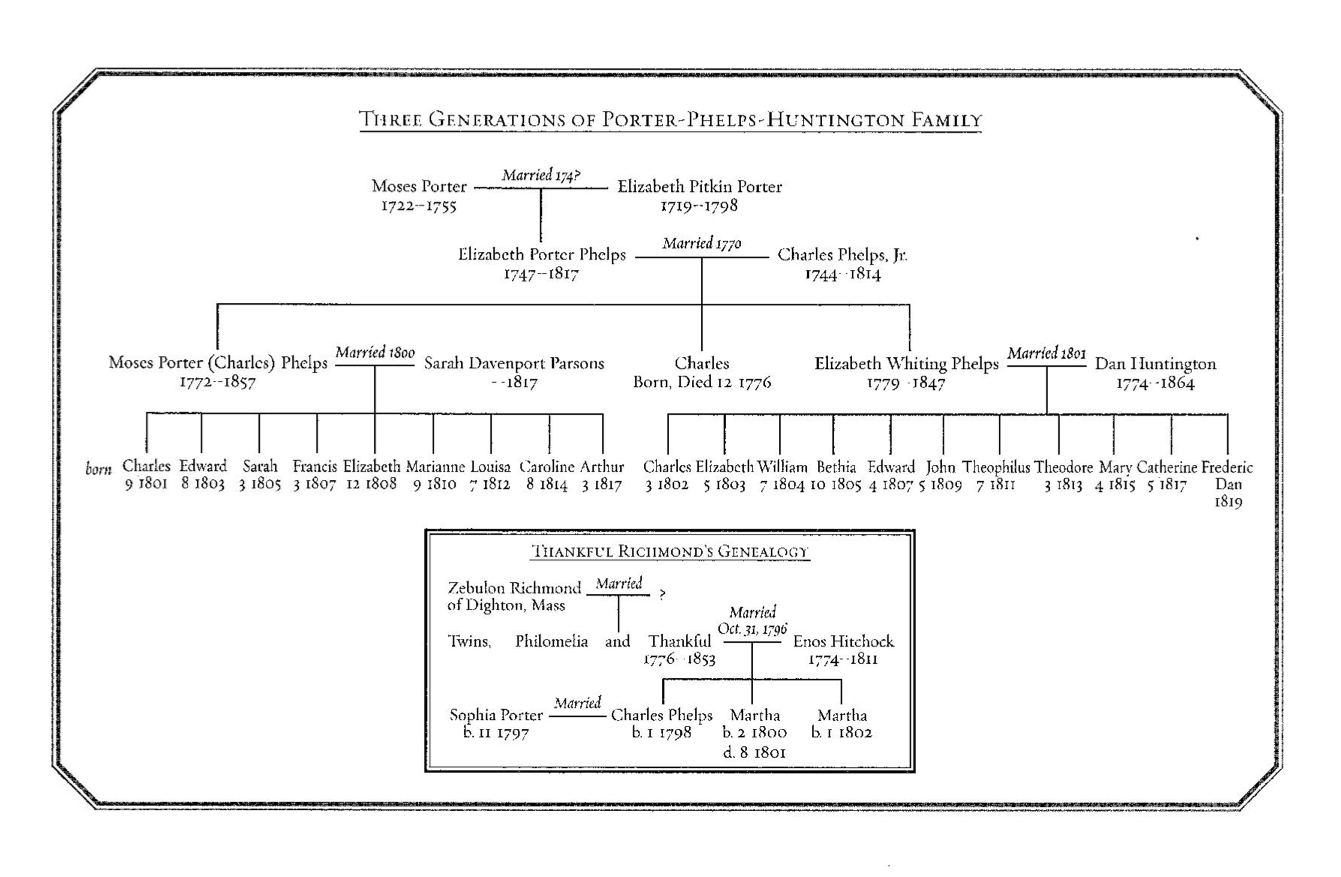

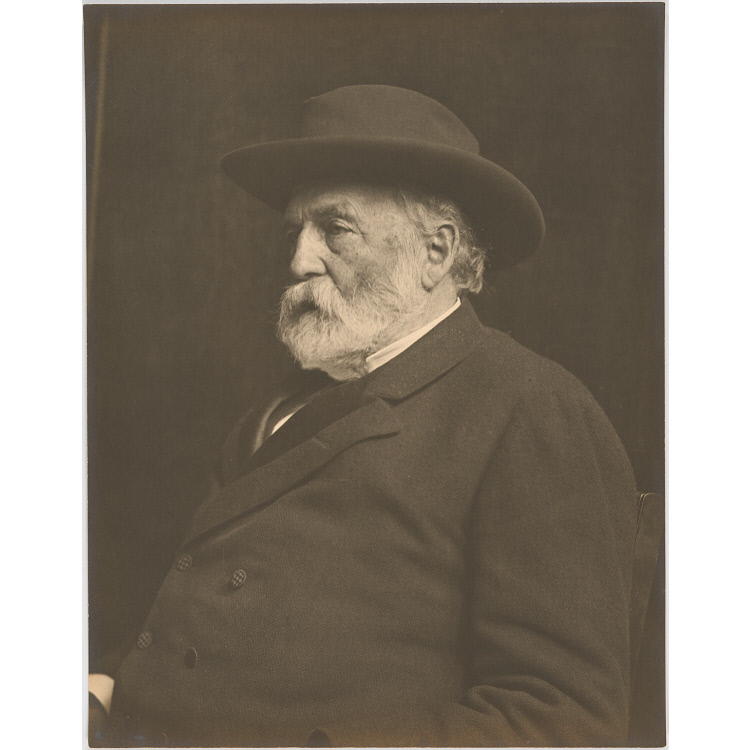

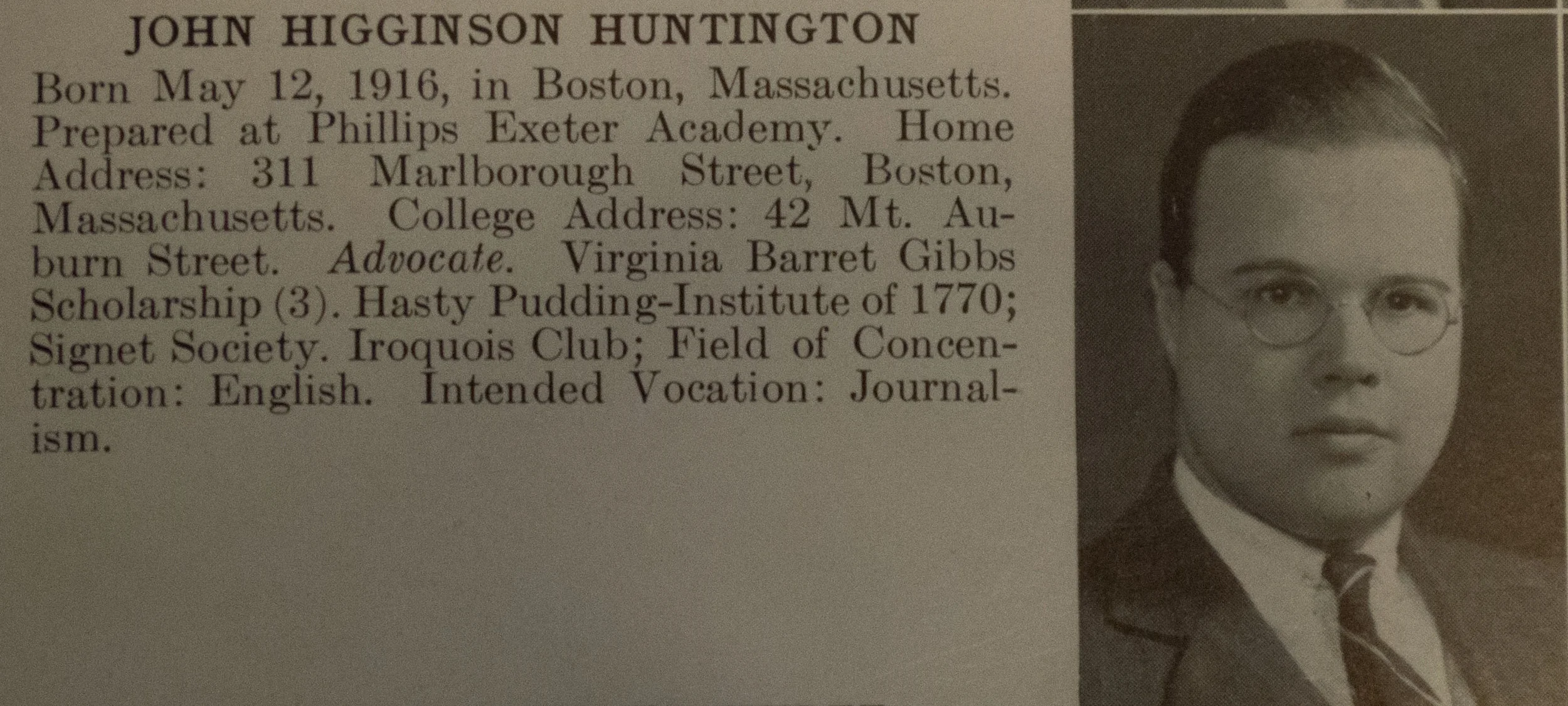

Moses “Charles” Porter Phelps sat down in 1857, the same year he passed away, to compose his autobiography. He wrote,

“The unsteadiness of my brain and the tremulousness of my eyes have prevented me from making much progress in the memoranda… and as the difficulty seems to have increased considerably within the last two or three weeks, I may probably be unable to enter into any minute or regular details of incidents that occured in our family history subsequent to the birth of Edward…” (32)

But in the eloquent accounts that follow, Charles still found a place for heartfelt remembrances of the two most beloved women in his life - his first wife, Sarah Parsons, and his mother, Elizabeth Porter Phelps. Sarah was described with grey eyes, “rather mild than piercing, and the combined expression of her countenance indicating at once the soundness of her understanding, and the tenderness of her heart.” (79) Elizabeth, though not of the same “strong and vigorous” intellectual powers, “was a most indefatigable reader.” And as her son remembered best, Elizabeth’s “religion was deep seated in the heart, and [she] was rigidly Calvinistic, as was then the prevailing creed of all New England.” (83)

In his final days, Phelps wondered whether his mother - and resultantly, he too - were governed by an oppressively incomplete image of God. “I think she must have viewed the power and sovereignty of GOD as overshadowing all his attributes of Love and Mercy” (83). The threatening image of a God who only judged and destroyed still lingered from his upbringing, and he had no doubt that in his mother’s adulthood, the same “shade of gloom often overspread the usually bright and cheering prospects of [her] religious experience.” A dutiful follower of preached Christian principles, she was impeccably kind and careful in her speech, but perhaps easily burdened by self-criticism and fear of retribution. “In mixed society she was cautious and guarded in her conversation, and I never heard her speak evil of any one. The law of kindness dwelt always upon her lips.” (83)

Charles recalled his earliest idea of God as “all powerful, angry - and world hating.” But his knowledge of the Bible, the story of Christ’s sacrificial love… didn’t match up.

“And yet this was the Being required to love — a Being who, with such conceptions as I could then form of him, I could not possibly regard except in the light of an enemy, who was ready with uplifted arm to crush and destroy me.” (84)

Taking his sister’s lead in the 1820s, Phelps had converted to Unitarianism, where he found a fresh lens through which he could consider God and the Bible. Unitarianism distinguished each part of the Holy Trinity as completely separate entities, sometimes defining Jesus as a son, but not a part of God the Father. Still, Charles sought and struggled to define a God that would give him hope. He continued,

“Indeed such is the image, which even to this day is very apt to rise spontaneously in my mind when the thought of God presents itself. The reasoning faculty may do much to produce true and correct results at last, but I have to this day found it impossible wholly to obliterate the deep impression made upon me by the teachings, feelings, and associations of my early youth. And even now, when standing on the verge of life, a cloud of doubt and despondency often settles down on the mental vision — and almost for the time, extinguishes every hope that the Gospel would inspire.——— But perhaps all this may be only the natural working of the carnal and unrenewed heart.” (84)

Like his mother’s later diary entries, Charles’ autobiography served as a space for some of the most challenging and time-ripened reflections. He grappled with the dichotomy between persistent fears of a hateful judgment and that “very hope that the Gospel would inspire.”

Click to peruse thoughts from Elizabeth’s diaries at In Elizabeth’s Words, learn about Charles Phelps, or read about Charles’ property established across from Forty Acres at Phelps Farm.

Sources

Phelps, Charles (Moses) Porter, Autobiography (1857) Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers Box 10 Folder 21 Amherst College Archives and Special Collections

Biographical sketch of (Moses) Charles Porter Phelps, Finding Aid, Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers. 1987-88.