“In this world, nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” - Benjamin Franklin

A folder entitled, “Financials, Estate of Gladys Huntington,” was recently opened within the collection of papers of Constant and Gladys Huntington, donated to the museum in 2020. The folder is full of correspondence regarding tax bills and other mundane aspects of life, but often these informational documents provide fascinating insight into the personal lives of people no longer with us.

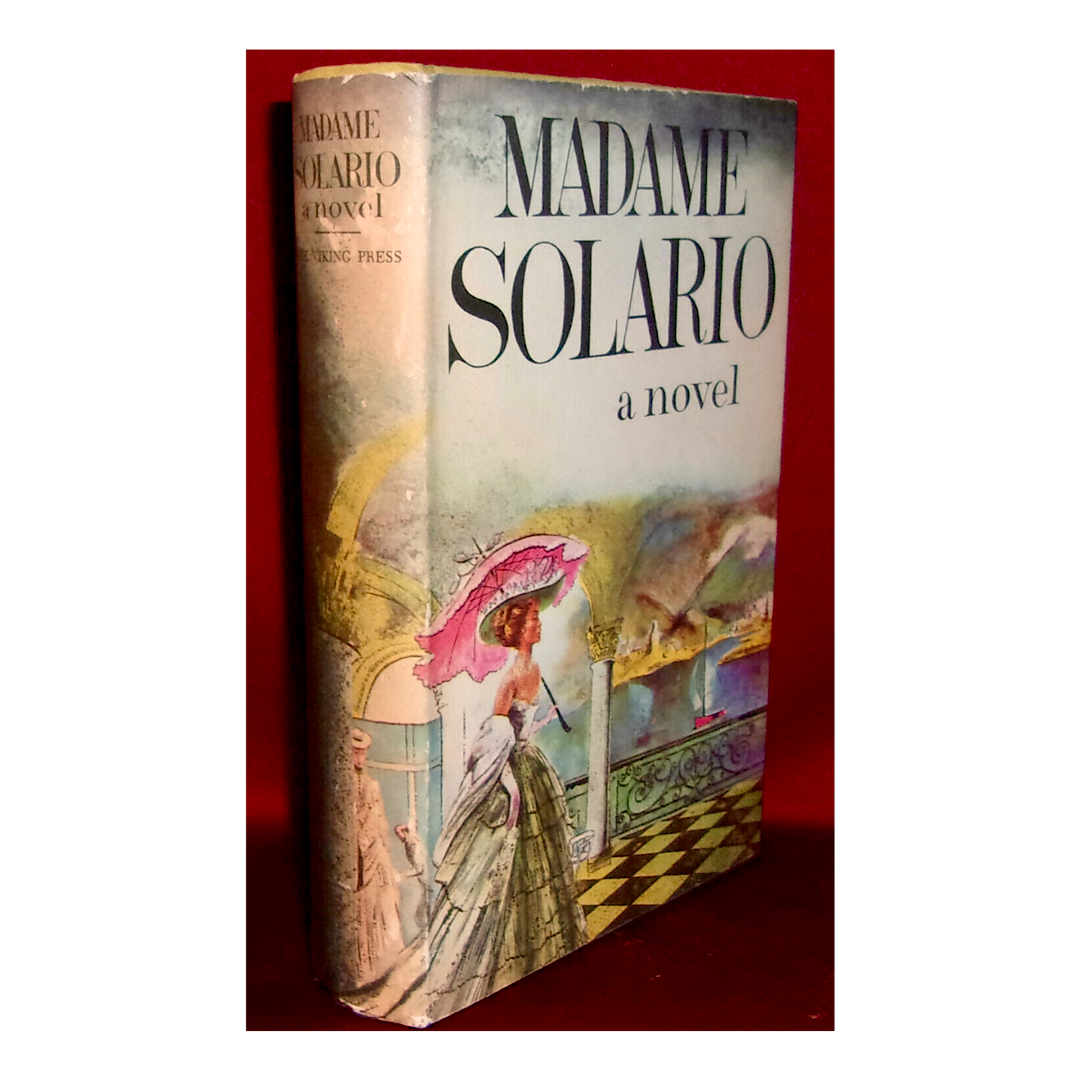

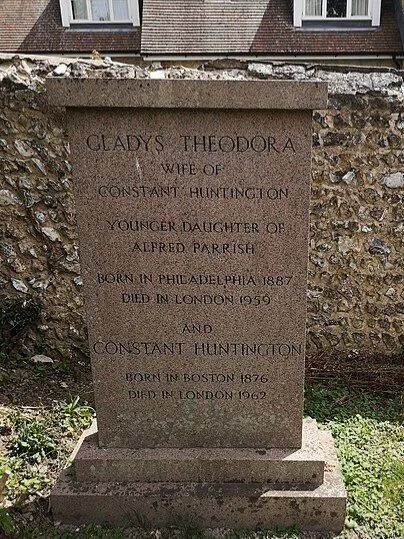

For two and a half years following the suicide of his wife Gladys on May 31, 1959, Constant Huntington corresponded with his legal representation, Dickerman Hollister of the firm Choate, Reynolds, Huntington & Hollister in New York from the Huntington’s residence in London. The purpose of this repetitive correspondence was to settle the Internal Revenue Service tax bills accruing on Constant’s personal income and Gladys’ estate from the previous three years. The continued revenue from Gladys’ book Madame Solario resulted in an increasingly expensive and time-consuming feat for the eighty-four year old widower who had successfully minimized his annual tax bills up until the time of her passing.

Gladys’ book Madame Solario made $3,361.66 in 1957, the year after its initial publication in August of 1956. Adjusted for inflation, that amounts to $32,204.34 - an impressive income for just a year of sales of an anonymously-written novel. While the revenue streamed in, Gladys’ name wasn’t attributed to the authorship of the book until 1986, thirty years after the book’s publication.

Seven months prior to Gladys’ death, a sizable amount of money, $53,422.12, was withdrawn when Gladys’ trust at Girard Trust Corn Exchange Bank in Philadelphia was closed. This concerned Constant’s lawyer Mr. Hollister, for fear that taxes plus interest would be accruing on that amount if it had been spent. “This money was paid out in October and November 1958 and it is imperative that we have a fairly detailed accounting of what happened to that money between those dates and Mrs. Huntington’s death. The Girard Trust seems to think it was all given to you. You tell me that that was not so; that some of it was spent, some given to other people and some invested. Please give me the particulars.” Adjusted for inflation, the amount today would be $511,778.21… a sizable amount to be missing.

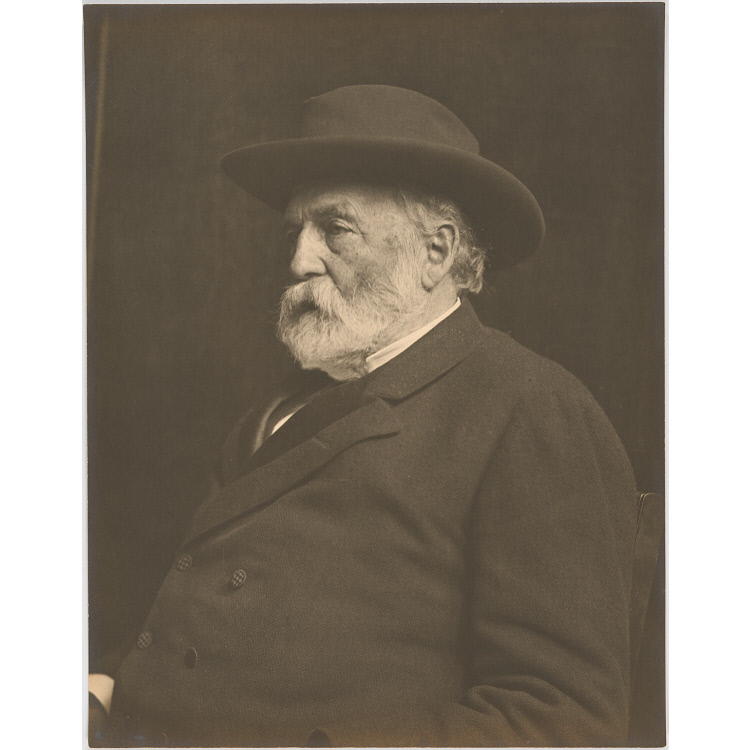

Constant’s reply to Mr. Hollister’s concern regarding the missing sum was sent on March 14, 1960, in which he details their financial holdings and habits. After explaining that Gladys’ wealth originated from her trust at Girard and the sales / royalties of her book, Constant says that he oversaw her accounts personally. Constant closes his reply by stating that after he has enjoyed such financial comforts because of Gladys’ trust, he “should like to do the same for my grandchildren, and perhaps you can tell me how.”

Throughout the correspondence between the two men, direct answers are rarely given to Mr. Hollister’s questions asked of transactions, account closings, and previous tax bills. Constant’s advanced age, multinational financial entanglements and declining mental faculties are made evident throughout the correspondence between he and Mr. Dickerman Hollister: the check which Constant forgot to attach to his letter, or the incorrect amount listed once the check was sent. (Instead of $309.09, Constant accidentally sent one for $309.90, which further delayed the settlement of his expanding tax bill.)

Constant’s letter apologizing to Mr. Hollister for his “further manifestation of old age… the worst of it is that this sort of thing happens all the time!” April 26, 1961.

The last correspondence between the two men is dated June 12, 1961 - a year and a half before Constant’s death at his home in London on December 4, 1962, at the age of eighty-six. In his last letter to Constant, Mr. Hollister thanks him for his most recent payment of $121.95 to the IRS, and tells him, “I am glad to note that for 1961 and the future your American tax problems will be taken care of by your English accountants.”

References:

“Gladys Huntington, Madame Solario.” https://persephonebooks.co.uk/products/madame-solario

Constant Huntington papers referenced:

June 11, 1959; December 4, 1959; February 24, 1960; March 14, 1960; April 17, 1961; April 26, 1961; June 12, 1961.