Elizabeth and Moses Porter’s Forty Acres, 1752-1770 | Elizabeth Porter and Charles Phelps’ Dairy Enterprise, 1770-1817 | Farm to Summer Home, 1817-1928

Farm to Summer Home, 1817-1928

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed a gradual shift in land stewardship practices at Forty Acres from a substantial farm to a romanticized and pastoral family retreat for the Huntington family. Though farm activities persisted at Forty Acres, they became increasingly removed from larger agricultural trends in the region. By the latter decades of the nineteenth century, the farm became more of a gentleman’s hobby farm than a substantial economic endeavor. Put another way, farming was increasingly tied to the family’s sense of tradition and heritage rather than a source of financial support—at least for the Huntingtons, though not for the men and women they employed to continue stewarding this landscape as both a farm and a pastoral summer home.

Broom corn grown in the Connecticut River Valley produced brooms such as this one in the museum’s collections. Photograph courtesy of Brian Whetstone.

Elizabeth Whiting Huntington and her husband Dan returned to Forty Acres in 1817 and continued many of the land management strategies of Elizabeth’s parents. In 1829, the pair “[took] the farm on shares.” As head of the family Dan Huntington deployed a range of strategies to keep the farm profitable by embracing almost every trend in Connecticut Valley agriculture in these first decades of the nineteenth century. By constantly readapting the farmstead to these emergent trends, the farm at Forty Acres remained remarkably dynamic even as active farmland continued to dwindle as Dan and Elizabeth sold farmland over the nineteenth century. The Huntingtons continued to raise sheep and cattle, and kept poultry. They were less invested than previous generations in both dairy and pork, but grew Indian corn, as well as rye, oats, and wheat. Like Elizabeth and Charles Phelps, they maintained an apple orchard on the southern hillside of Mount Warner, and on a slope north of the house at Forty Acres, from which they produced both applesauce and cider. In the 1820s, the Huntingtons joined their counterparts around the Valley, and especially in Hadley, in the raising of broom corn. By 1810, 70,000 brooms were produced each year in Hampshire County. By 1842, Dan Huntington was selling large quantities of broom brush (in batches over 1,100 pounds) and taking brooms in batches of 400 to 800 to the Boston market. In the 1830s, the Huntingtons also flirted with silk, introducing silkworms to the site. Huntington sold his cocoons to the Nonotuck Silk Mill in Florence. Elizabeth Whiting Phelps Huntington died in 1847. Her adoptive sister Thankful Richmond Hitchcock—who lived near her siblings by 1850, in the house of her daughter and son-in-law, Martha Keyes Hitchcock and Giles E. Smith—died in 1853. Dan Huntington continued to farm, though in a demeanor of retreat. The farmstead shrank in the 1840s as land was sold to settle debts and fund the Huntington children’s education. Still, the 1850 agricultural census enumerated 70 acres of tillage on a farm valued at $10,000, more than double the town’s average, and triple the town’s median. Only one farm—Phelps Farm across the street—was valued more highly, and only two other farms matched his on that measure. Dan Huntington died in 1864; his will left the property to youngest son Frederic Dan Huntington.

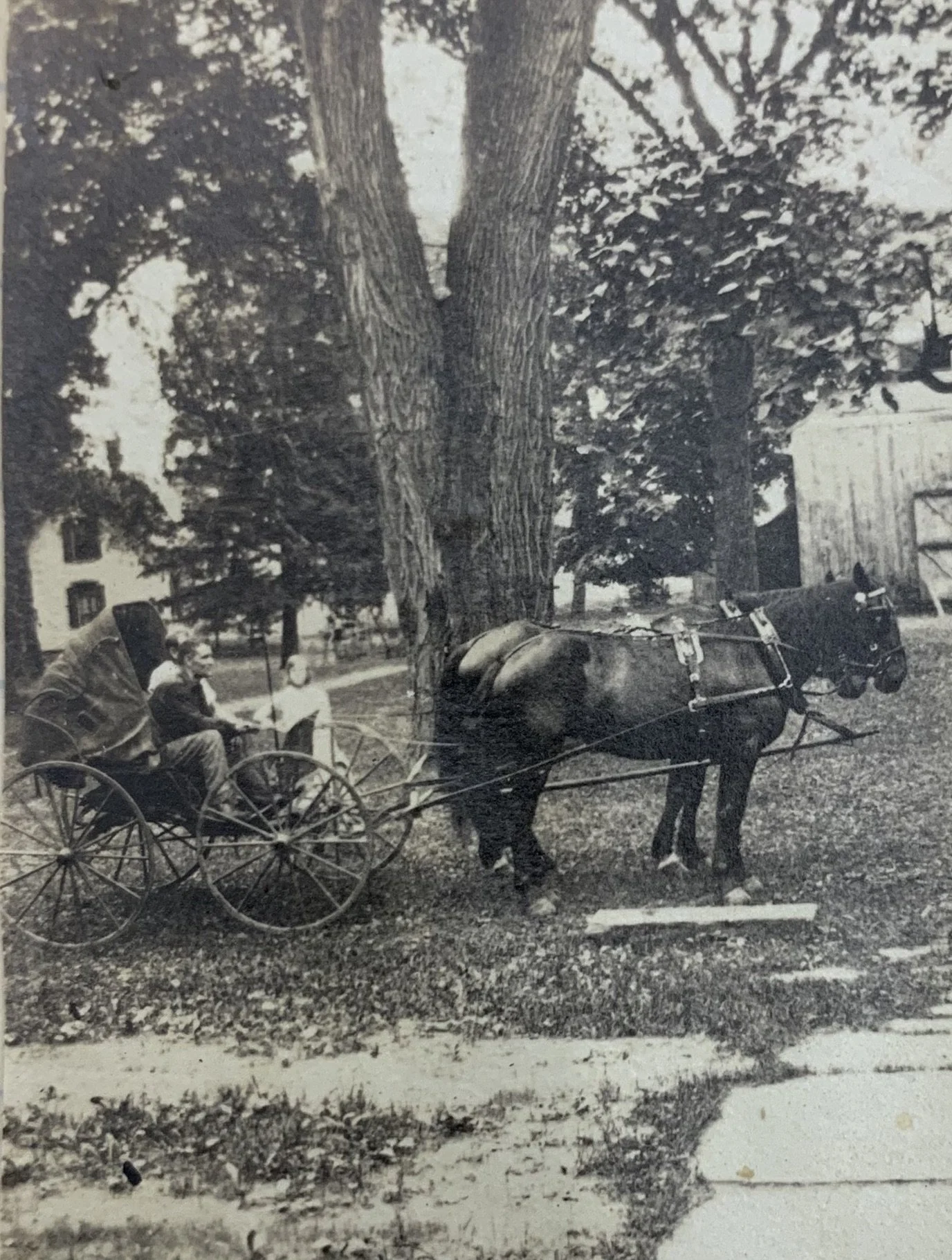

In this circa 1900 image, Bishop Frederic Dan Huntington poses “as a farmer” at Forty Acres, reflecting his romanticization of the family farm as he was increasingly removed from farm labor. Source: Unprocessed collections of (Moses) Charles Porter Phelps, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

In the ensuing decades—sometimes called the “Country Place era”—the house at Forty Acres and its grounds responded to and drove two important developments in the region’s cultural history: shifting relationships to the natural world that increasingly prioritized aesthetic over agricultural value, and the active celebration—and invention—of “old” New England. These developments reimagined land stewardship at Forty Acres as an endeavor bound to family memory, tradition, and history more so than productive agriculture. Frederic Dan Huntington and his wife Hannah Dane Sargent Huntington used the house at Forty Acres as a summer house, usually arriving in June and leaving in September or October. A caretaker oversaw the property through the winter. In recreating the farm as a summer residence, the Huntingtons were in keeping with a wider trend across the region, in which affluent families spent their summers “rusticating” in historic houses. By the 1890s, across the region, New England elites—“summer colonials”—retreated to historic houses to escape the heat of increasingly crowded and chaotic urban settings and perform a nostalgic embrace of the region’s rural past. As Forty Acres became a summer retreat, John Morrison’s onetime ornamental North Garden now shifted to include plantings popular in Victorian gardens: hollyhocks, roses, flower-de-luce, and verbena. Despite this emphasis on more romanticized landscape stewardship, Frederic Dan Huntington continued to engage in agriculture at Forty Acres and made alterations to the landscape to support farming, producing rye, oats, and corn. In 1859, Frederic Dan Huntington’s son Theodore persuaded him to sell the family’s sole remaining lot on Mount Warner—now distant and no longer contiguous to other holdings—and instead to purchase “about half” of the farm of William P. Dickinson to the east, expanding his woodland and pasture. Early on he kept “a few grade cows” and “then some Kerry cattle,” but eventually committed to Jersey (sometimes called Alderney) cows. In 1865, Huntington built an ice house next to the cheese room that replaced an earlier system by which butter and meat were lowered into a “well-shaft” through the 1797 Kitchen floor. He also added a silo to serve the farm’s livestock. With the family away most of the year, help was hired to oversee farm operations. Irish immigrant and hired farm manager John Breckenridge (b. ca. 1826) “presided over our farmlabor-contingent.” Sometime before 1880, Frederic Dan Huntington had a small cottage built near the 1782 great barn. George Shipperly (1834–1909) and Susan Shipperly (1834–1891), an English couple who lived onsite as caretakers, occupied the cottage and assisted in the work of the farm. They would remain until September 1884, and were succeeded by a Mr. and Mrs. Doyle, who ran the farm between Frederic Dan Huntington’s death in 1904 and Hannah’s in 1910.

This 1922 photograph is the only known image of the caretaker’s cottage at Forty Acres. Shown here at the left, it stood just east of the 1782 great barn before burning in the 1920s. Source: James Lincoln Huntington, Journal and scrapbook of the house at "Forty Acres" in Hadley, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Frederic Dan Huntington died at Forty Acres in July 1904; the bishop’s eldest son George did not inherit Forty Acres as planned, as he died, suddenly, on that same day. The farm was instead inherited jointly by George's six surviving children: Henry Barrett Huntington, Constant Davis Huntington, James Lincoln Huntington, Michael Paul Huntington, Catherine Sargent Huntington, and Frederic Dane Huntington. The deaths of Frederic and George Huntington accelerated the farm’s turn towards romanticized and aesthetic land stewardship practices, but farming nevertheless persisted at the site. George’s eldest son, Henry Barrett Huntington—an English professor at Brown University—tried to run a dairy farm at Forty Acres, though he retained his primary residence in Providence, Rhode Island. Mindful of emerging state requirements around the inspection of dairy farms, Henry Barrett Huntington built a cow barn (attached to the southwest corner of the 1782 great barn), added eight to twelve Jersey cows, and hired an overseer who lived in the caretaker’s cottage. The farm also kept pigs, poultry, and horses. But milk surpluses meant a weak market, and in 1911, the farm recorded a “dead loss” when a local creamery failed. In the end, running a farm from a distance proved untenable, and Henry Barrett Huntington gave up the effort by 1918. In the 1920s, there was still some lingering dairy activity, as well as pigs and poultry. In the fields grew corn (though no longer hay and grain), and probably potatoes and onions. It was Henry Barrett’s younger brother, James, who would solidify new land stewardship practices at the farmstead that would enhance the farm’s romantic qualities.