Adapting to Climate Change, 1928-Present

Dramatic changes in land stewardship practices have characterized the last century at both Forty Acres and Phelps Farm. Over the 1920s and 1930s, James Lincoln Huntington transformed Forty Acres from a working farm to a museum and historic site. This change involved new land stewardship practices that focused on enhancing the romantic and aesthetic qualities of the landscape surrounding Forty Acres. The end of the dairy business at Phelps Farm in 1978 meant that many of the farm’s once-bustling agricultural buildings fell into disuse and disrepair. Despite these changes, farming and agriculture have persisted at both sites in new forms while outdoor recreation and conservation have guided the ways these lands are stewarded into the twenty-first century. But climate change from human activity and the increased frequency of extreme weather events jeopardizes the museum’s capacity to care for the cultural, environmental, and historical resources at both Forty Acres and Phelps Farm.

Mollie and Maggie, two maids employed by James Lincoln Huntington, stand on the “back terrace” in 1934 next to a former granite sink utilized as a bird bath. Note the cornfields in the background and the tree line marking the Connecticut River. Source: James Lincoln Huntington, Journal and scrapbook of the house at "Forty Acres" in Hadley, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

When James Lincoln Huntington set out to make his family’s ancestral home a museum in the mid-twentieth century, he viewed many of the working and agricultural spaces of the farmstead’s history as an impediment to his historical and aesthetic vision. While agriculture still continued in the nearby fields, James set to clearing the immediate landscape surrounding the house of working buildings. Over the 1920s, James removed several agricultural outbuildings, including a corn crib, ice house, bull pen, and cow barn; in 1928, James demolished and reconstructed the house’s corn barn; and a fire in 1929 destroyed the manager’s cottage at Forty Acres. James wrote that in making these changes, “the true spirit of this remarkable place has been purified and emphasized by what we have done,” a belief that culminated in 1929, when he deconstructed the 1795 carriage house, salvaged several beams, and replaced it with a residence he called the Chaise House in 1930. These changes manifested in other ways on the landscape and created more romanticized landscape elements at Forty Acres. In 1929, James sold the 1782 great barn to Henry R. Johnson and his photographer brother, Clifton Johnson, who relocated the barn to the center of Hadley where it today operates as the Hadley Farm Museum. On the remains of the barn’s stone foundation, Huntington created a terraced sunken garden in 1931 that included a fish and lily pond in the barn’s former manure. The new sunken garden solidified new land stewardship practices that focused on the aesthetic and pastoral qualities of the landscape, rather than productive or agricultural uses.

Floodwaters from the 1936 flood overran Phelps Farm, whose outbuildings and farmyard are pictured here. Source: James Lincoln Huntington, Journal and scrapbook of the house at "Forty Acres" in Hadley, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Aestheticized landscape features like the sunken garden did more than enhance the romantic qualities of Forty Acres, they helped adapt the landscape to be more resistant to climate change and extreme weather events. In addition to the sunken garden, James terraced and landscaped a long berm that separated the house from the fields and river to the west to protect the house and its historical collections from flooding. James described this landscape feature as the “back terrace” and—like the sunken garden—repurposed fragments of the farm’s working spaces into decorative embellishments by relocating an “old granite sink” for use as a bird bath on the back terrace. Following floods in 1927, 1933, and 1936 and again after a hurricane in 1938, James took more aggressive measures to protect the house against floodwaters. The 1927 and 1933 floods penetrated the house’s cellar, damaging wiring and the furnace. Following the 1933 flood, James constructed a stone retaining wall around the back porch in 1933. Despite these efforts, the 1936 Connecticut River flood still exacted significant damage to both Forty Acres and Phelps Farm—James observed that both the 1933 and 1936 floods were “the two worst floods” in Hadley’s history. Both penetrated the house’s cellar and damaged several pieces in the museum’s collections. The 1938 hurricane accelerated Huntington’s efforts to make the landscape at Forty Acres more climate-resistant. In the wake of the hurricane, Huntington consulted neighbors and determined that “Siberian elms” and “purple beeches stood the hurricane better than any other shade trees because its roots are so deep and its boughs all sturdy” and planted several beech and elm trees shortly thereafter. In all of these climate resiliency initiatives, James was assisted by laborers—many of whom were Polish immigrants in the surrounding community—who laid stone walls, graded and terraced the land, mended and repaired flood- and hurricane-damaged structures, and planted, pruned, or removed the property’s damaged trees.

Trees at Forty Acres sustained significant damage from the 1938 hurricane, prompting James Lincoln Huntington to plant more climate-resilient species like purple beeches and Siberian elms. Source: James Lincoln Huntington, Journal and scrapbook of the house at "Forty Acres" in Hadley, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

John Sessions and his daughter, Sally, ride a tractor in the fields still present behind Forty Acres, circa 1945. Source: James Lincoln Huntington, Journal and scrapbook of the house at "Forty Acres" in Hadley, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

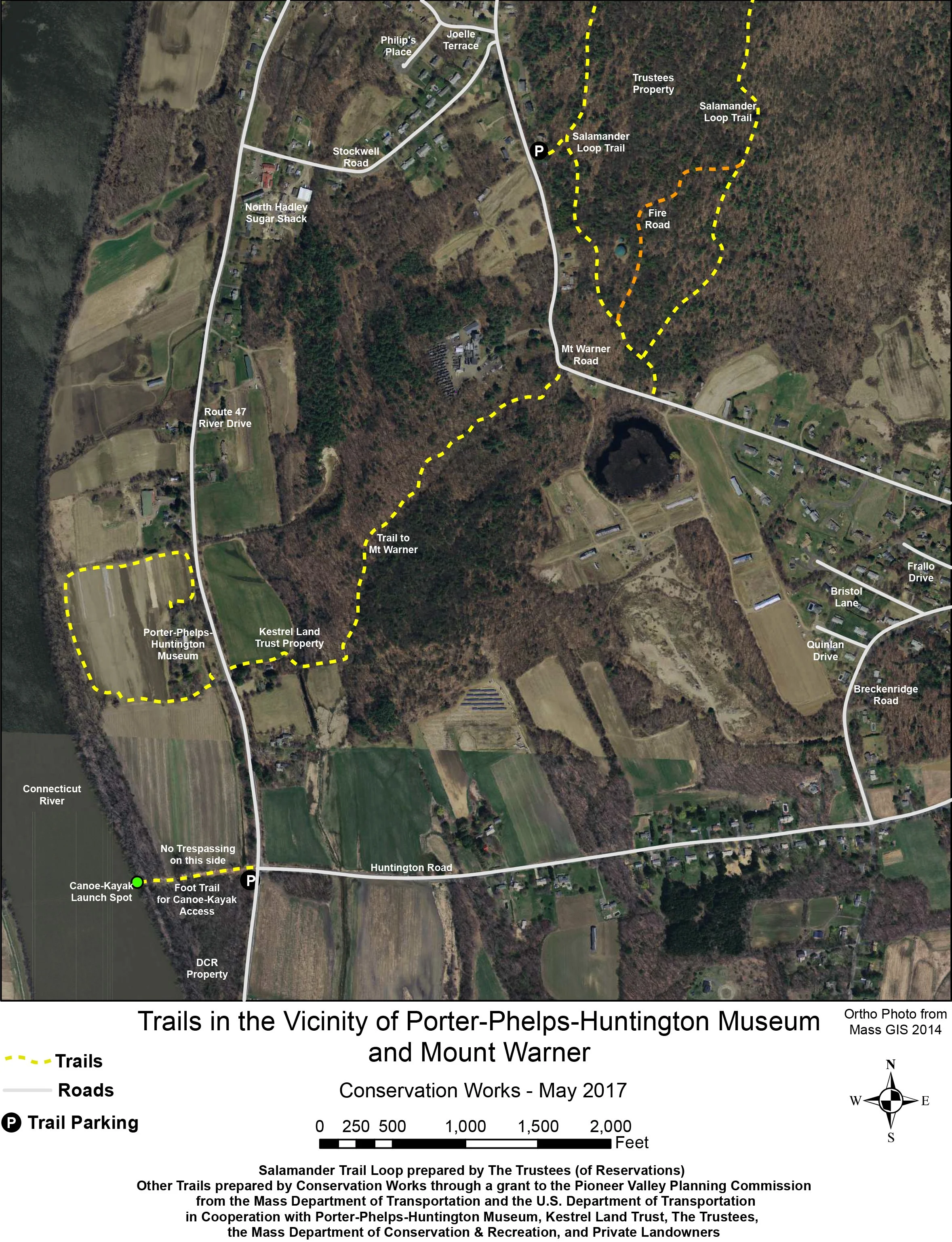

Hiking trails near the Porter-Phelps-Huntington museum, courtesy of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Foundation.

Traditional agricultural practices, environmental preservation, and recreation continue to persist at both Forty Acres and Phelps Farm, but these land stewardship practices are threatened by climate change. In the 1980s, the agricultural fields surrounding both sites were placed within Massachusetts’ Agricultural Preservation Restriction (APR) program. The APR program preserves agricultural land through deed restrictions that prohibit eligible farmland from being built on for non-agricultural purposes that could be environmentally harmful. At Phelps Farm, this farmland continues to be cultivated by Parsons Farms, who began renting the land in 1979; Chip Parsons utilized Phelps Farm’s former dairy barn to house sheep until 2000. At Forty Acres, partnerships between the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Foundation, Kestrel Trust, the Valley Land Trust, Nature Conservancy, and the Trustees of Reservations have helped protect some 350 acres of land in Hadley and created the National Connecticut River Scenic Byway in addition to the museum’s co-management of the Elizabeth Huntington Dyer Field and Forest Conservation Area with Kestrel Trust. The museum, Kestrel Trust, and the Trustees of Reservations also manages several hiking and walking trails. Over the last several decades, the museum has embraced more sustainable land use practices by replacing monoculture fields behind Forty Acres with organic vegetable farming on Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) model. In 2021, the museum initiated a pilot program in collaboration with Stone Soup CSA and the non-profit organization All Farmers whereby a group of Somali farmers planted a few acres of millet and sorghum for their own profit and use.

Flooding in July 2023 devastated crops behind the museum. Shown here are the fields behind the house with floating invasive plants in the foreground removed as part of the first phase of the USDA pollinator implementation plan. Photograph courtesy of Brian Whetstone.

But these land conservation initiatives are increasingly jeopardized by climate change and flooding from the Connecticut River. Research conducted by the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation predicts that greenhouse gases and other man-made emissions that contribute to climate change will increase flooding and extreme precipitation in Massachusetts by at least 25% until 2100. Already, this increased precipitation has generated greater unpredictability in the Connecticut River’s traditional flood patterns, producing devastating results for the region’s farmers and threatening the historic resources at Forty Acres and Phelps Farm. A flood in 1984 penetrated the basement of Forty Acres for the first time since the historic floods of 1936 and 1938, making it the third-worst flood in the history of Forty Acres. In July 2023, dramatically increased rainfall swelled the Connecticut River past its banks, wiping out or contaminating acres of farmland with sewage and other chemicals from upstream. Dramatic fluctuations in temperature also wreak havoc on local plants and animals. The museum is presently engaged in implementing an on-site pollinator program at Forty Acres in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture that will provide a natural habitat for pollinators and reduce some of the risks posed by extreme weather. Still, hotter summers, colder winters, and greater precipitation will continue to impact the museum—whose interior is not climate-controlled—and its collections. Increased humidity and variations from hot to cold will accelerate the deterioration of the museum’s collections and interiors by expanding and contracting historic materials and finishes. At Phelps Farm, climate change continues to threaten the historic 1816 farmhouse that has largely been exposed to the elements for nearly 40 years. Without immediate action to address climate change, the impacts of extreme weather will continue to intervene with land stewardship at Forty Acres and Phelps Farm.