Neoclassical Looking Glasses

_

Figure 2

While mirrors are known to have existed since at least 3000 BCE, the process for creating the silvered glass mirrors we are familiar with today was not refined until the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by Venetian glassmakers. With French competitors’ innovations in production methods and the European aristocracy’s “mirror craze” in the seventeenth century, mirrors became more common, though still a luxury item.[i] Thus, by the time Charles Phelps (1743-1814) purchased many of the mirrors hanging in the Porter-Phelps-Huntington house in the late eighteenth century, such decorative items were probably still expensive, but becoming a more common feature of well-to-do households.

Figure 3

These two neoclassical looking glasses were likely purchased in the 1790s, when Charles Phelps updated the parlor in the Federal style (figures 1 and 2).[ii] Although carved, gilded wood makes up the primary construction of the frames, the detailed ornamentation seems to be made of a mixture of gesso and glue. A glimpse of this plaster-like material is visible in a crack in one of the mirror’s floral details (figure 3). More time- and cost-effective than carving elaborate details by hand, this molding process also allowed artisans to create “the more delicate, low-relief effect sought by neoclassical designers” (Barquist 325).

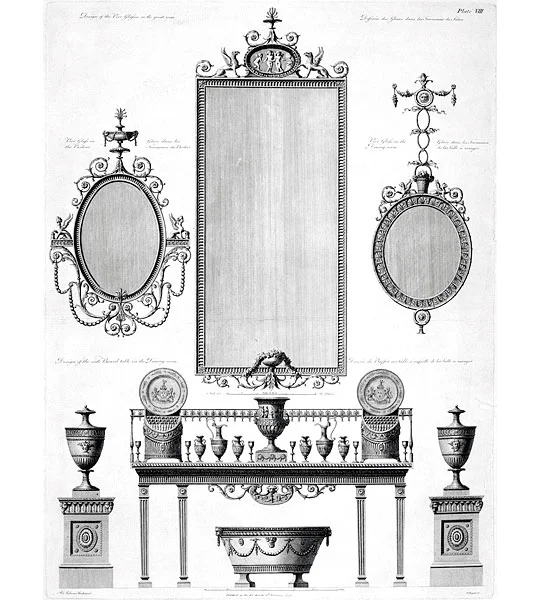

Exhibiting more restraint than earlier rococo styles while maintaining similar flourishes, neoclassical furniture design was characterized by its delicate, airy quality and Greco-Roman-inspired ornamentation.[iii] These looking glasses appear to be influenced stylistically by the designs of eighteenth-century British architects Robert and James Adam, especially when compared with a 1773 illustration from The Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (figure 4). The oval looking glass in particular shares the beaded inside edge, intricate spiraling decoration along the top and bottom of the frame, and urn-shaped finial depicted in the Adam brothers’ design. While neoclassical styles were popular in England and France from the 1760s, neoclassicism did not catch on in America until the end of the eighteenth century; however, the Adamesque style continued to influence American craftsmen into the nineteenth century.[iv]

Figure 5

The place of manufacture for looking glasses found in early American homes is, as many historians acknowledge, notoriously difficult to pinpoint.[v] David Barquist, curator of American decorative arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, explains the challenges: “Although the exclusive use of native woods and the occasional presence of a maker’s or retailer’s label provide strong evidence that a given looking glass was made in the United States, it is frequently impossible to fix its origin conclusively, since American woods were exported to England and there used in frame and furniture making. In Federal, as in colonial times, Americans relied exclusively on European glass plates, since American glasshouses apparently did not produce plates of this quality until the second half of the nineteenth century” (322).

Figure 6

Although most early American looking glasses were imported, we have reason to believe that some of the looking glasses in the Porter-Phelps-Huntington house may have been constructed by American craftsmen. With rich mahogany veneer, delicate trailing vines along the sides, and crowning ornamentation of a Grecian urn finial, the rectangular looking glass in the Porter-Phelps-Huntington museum’s front hall (figure 2) resembles designs by Hartford looking glass maker Nathan Ruggles (1774-1835) (figure 5).[vi] Commenting on another looking glass that bears a striking similarity to the one purchased by Charles Phelps (figure 6), David Barquist affirms that “no English version of this type of frame has been identified” (324). Given the fact that Charles Phelps purchased other furnishings from local artisans (including six chairs from Samuel Gaylord), it would not be entirely surprising if this looking glass frame were actually crafted in New England.

Mirrors have long been a potent symbol for reflection, interiority, and self-awareness, and we can only imagine what kind of metaphysical resonances these looking glasses might have had for the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century inhabitants of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington house.[vii] Other pieces of evidence, however, provide us with clues that the home’s residents particularly valued contemplation and introspection. For instance, the very architecture of the house was designed to construct spaces for quiet meditation. Organized with rooms branching off of a central hall rather than clustered around a central hearth, the house, according to Elizabeth Pendergast Carlisle, “creates private spaces that invite withdrawal and reflection: their separation from clearly defined work spaces fosters other activities: writing, reading, and meditation, the latter two encouraged from the pulpit in Calvinist New England” (13). Such spiritual reflection is evident in the diary that Elizabeth Porter Phelps (1747-1817) kept from the age of 16. In an entry from November 23, 1800, written the week of her birthday around the time that her husband Charles would have purchased the neoclassical looking glasses, Elizabeth writes, “Wednesday fifty three years have I seen thro the sparing mercy of God. Tis pleasant to take a retrospective view of my past life, how many mercies, truly ‘tis all mercy—the whole has been goodness & faithfulness but still O God my eyes are unto Thee.” Shining a mirror on her past fifty-three years, Elizabeth takes a “retrospective view” of her life through the eyes of her Calvinist faith.

Over two centuries of history reflect back at us through the mirrors that remain on the Porter-Phelps-Huntington house’s walls to this day, and these artifacts merit further research. The Museum’s rare and valuable looking glasses surely have much more to tell us about changing decorative styles, global circulation of raw and manufactured goods, American purchasing patterns, and shifting definitions of selfhood in Federalist New England.

Sources:

- Barquist, David L. “American Looking Glasses in the Neoclassical Style, 1780-1815.” The Magazine Antiques 141.2 (February 1992): 320-31.

- Carlisle, Elizabeth Pendergast. Earthbound and Heavenbent: Elizabeth Porter Phelps and Life at Forty Acres (1747-1817). New York: Scribner, 2004.

- Hutchins, Catherine E., ed. American Federal Furniture and Decorative Arts from the Watson Collection. Columbus, Ga.: The Columbus Museum, 2004.

- Melchior-Bonnet, Sabine. The Mirror: A History. New York: Routledge, 2001.

- Quimby, Ian M. G., ed. American Family Treasures: Decorative Arts from the D.J. and Alice Shumway Nadeau Collection. Lexington, Mass.: National Heritage Museum, 2005.

- Ward, Gerald W. R. and William N. Hosley, eds. The Great River: Art and Society of the Connecticut River Valley, 1635-1820. Hartford: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1985.

Endnotes:

[i] See Sabine Melchior-Bonnet 26.

[ii] As Ian Quimby explains, “the preferred term for early American reflection furniture is looking glasses, rather than mirrors, for this is the term used in the eighteenth century” (79). Fore more about the provenance of the looking glasses, see Gerald Ward and William Hosley (270).

[iii] See David Barquist 322, 329.

[iv] See Barquist 325.

[v] Quimby, for instance, comments that “Of all the forms of early American furniture, looking glasses pose the most difficult problems when it comes to establishing their place of manufacture” (79).

[vi] See Catherine Hutchins 127.

[vii] For more on the shifting socio-historical valences of mirrors, see Melchior-Bonnet.